In the middle of the Great Depression, the Austrian town of Wörgl was in deep trouble and prepared to try anything. Of its population of 4,500, 1,500 people were without a job, and 200 families were penniless. Mayor Michael Unterguggenberger had a list of projects he wanted to accomplish, but there was not enough money to carry them out. These projects included paving roads, erecting streetlights, extending water distribution across the whole town, and planting trees along the streets.1 2

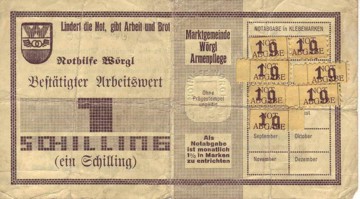

Rather than spending the remaining 32,000 Austrian Schilling in the town’s coffers to start these projects, he deposited them in a local savings bank as a guarantee to back the issue of a currency known as stamp scrip. A crucial feature of this money was the holding fee. The Wörgl money required a monthly stamp on the circulating notes to keep them valid, amounting to 1% of the note’s value.1 2 An Argentine businessman named Silvio Gesell had come up with this idea in his book The Natural Economic Order.

Nobody wanted to pay for the monthly stamps, so everyone spent the notes they received. The 32,000 schilling deposit allowed anyone to exchange scrip for 98 per cent of its value in schillings. Hardly anyone did this because the scrip was worth one Austrian schilling after buying a new stamp. But people did not keep more scrip than they needed. Only 5,000 schillings circulated. The stamp fees financed a soup kitchen that fed 220 families.1 2

The municipality carried out the intended works, including new houses, a reservoir, a ski jump and a bridge. The key to this success was the fast circulation of the scrip money within the local economy, fourteen times higher than the schilling. It increased trade and employment. Unemployment in Wörgl dropped 25% while it rose in the rest of Austria. Six neighbouring villages copied the idea successfully. The French Prime Minister, Édouard Daladier, visited the town to witness the ‘miracle of Wörgl’ himself.1 2

In January 1933, the neighbouring city of Kitzbühel copied the idea. In June 1933, Mayor Unterguggenberger addressed a meeting with representatives from 170 Austrian towns and villages. Two hundred Austrian townships were interested in introducing scrip money. At this point, the central bank decided to ban scrip money.1 2

Since then, several communities have issued local scrip currencies. None of them was as successful as the currency of Wörgl. The reasons probably are:

- There was no economic depression, and the economy could support interest, so introducing scrip money had little effect.

- If scrip money is not widely accepted, people will exchange it for regular currency if they can’t use it.

In Wörgl, the payment of taxes in arrears generated additional revenues for the town council, which the town council spent on public projects. Once the townspeople had paid their taxes, they would have run out of spending options and might have exchanged their scrip for schillings to avoid paying for the stamps. That never happened because the central bank halted the project.

There are, however, a few issues to consider. The economy of Wörgl did well without issuing debt because the money kept circulating. A negative interest rate induces people to spend the money they have, so no new money has to be borrowed into existence to stimulate the economy. A holding fee makes negative interest rates possible as you do not have to pay it when lending money. For instance, lending out money at an interest rate of -2% is more attractive than paying 12% for the stamps. If we can uncover the conditions for it to work, remove its flaws, and plan for the consequences, we can have a usury-free financial system.

Natural Money

Introducing negative interest rates in the global financial system may have great benefits. The website Naturalmoney.org features an in-depth research of the feasibility and consequences of negative interest rates.

If you like this post, then you might also like:

Joseph in Egypt

Ancient Egypt had a similar type of money for more than 1,000 years. There is an account in the Bible that may explain how this money came into existence.

The future of interest rates

In the long run most capital ends up in the hands of the capitalists. Negative interest rates are the logical consequence.

Latest revision: 6 April 2024.

Featured image: Wörgl bank note with stamps. Public Domain.

1. The Future Of Money. Bernard Lietaer (2002). Cornerstone / Cornerstone Ras.

2. A Strategy for a Convertible Currency. Bernard A. Lietaer, ICIS Forum, Vol. 20, No.3, 1990. [link]

[…] Austria: The Plan For The Future – The miracle of Wörgl […]

LikeLike

[…] taxation, democracy and even currencies and Keen rose to the occasion, describing the success of the Wørgl currency in the 1939s. They talked about the possible Scottish devolution. It is one thing to have a budget from the […]

LikeLike

[…] The miracle of Wörgl […]

LikeLike

[…] The miracle of Wörgl […]

LikeLike

[…] The miracle of Wörgl […]

LikeLike

[…] The miracle of Wörgl […]

LikeLike

Very interesting take on money, the human construction, which can be constructed to operate in any number of ways other than the mainstream illusions of money as part of Nature.

LikeLike

[…] community currencies, barter exchanges, local exchange trading systems, precious metals, crypto, The miracle of Wörgl and many other examples of ways that people can transact outside of the purview of the central […]

LikeLike

[…] community currencies, barter exchanges, local exchange trading systems, precious metals, crypto, the miracle of Wörgl and many other examples of ways that people can transact outside of the purview of the central […]

LikeLike