How well large groups make decisions depends on how we share information and form opinions. In this regard, there are two opposing ideas. These are the wisdom of crowds versus popular delusions and the madness of crowds. As a collective, we know far more than any individual, but collectives can act more stupidly than most individuals would alone. Individuals might be stupid, but in collectives, even the most intelligent people can act stupidly, most notably in collective action problems and when there is groupthink. As individuals, we are the cleverest species that ever roamed this planet. But as a collective, we are about to commit suicide.

How can that be? Groups behave differently than individuals. Groups are not merely the sum of the individuals in it. The properties of a group differ. An individual water molecule cannot form a wave, but water molecules in a lake can. And a group of starlings can fly in intriguing patterns. Collectives can cooperate and achieve more than individuals. Bees and ants demonstrate collective intelligence. They share information, for instance, about where to find food and use it collectively. Bees build beehives using a sophisticated division of labour, while ants can collectively defeat enemies many times their size.1

It is natural behaviour, and it emerged from evolution. Ants also demonstrate what can go wrong with collective intelligence. They follow each other’s trails. If an ant accidentally walks in a circle, an entire colony might follow it. They could end up walking in circles until they die. In this case, otherwise beneficial behaviour can go wrong with fatal consequences. That is collective stupidity.1

The same applies to us humans. Groups know more and do better in answering quiz questions than individuals. Francis Galton discovered the wisdom of crowds in 1906. He visited a livestock fair where an ox was on display. In a contest, the villagers could estimate the animal’s weight. Nearly 800 people participated. No one guessed the weight of 1,198 pounds, but the average estimate was 1,207 pounds, less than one per cent off.2

Galton concluded that this finding argued in favour of democracy. Taking every view into account, for instance, in Parliament, might produce good decisions. At the fair, people assessed the ox’s weight independently. They did not arrive at their estimate in a group process. And that could be a reason why it worked so well.2 Individuals, on aggregate, may make better estimates if each individual has an independent personal perspective.

If we can influence each other, we can go collectively crazy. We desire the approval of our peers, and that clouds our judgment. Autistic people may be an exception as they do not pursue the approval of others. People in groups can agree with ideas they believe are wrong. They can ignore their personal information and pass on the group’s views. That is an information cascade. Good information spreads in this manner. That is why it is usually beneficial. But misinformation spreads in the same way. Information cascades often occur with herd behaviour or individuals behaving the same way.1

YouTube makes use of herd behaviour. If you come across a video with ten million views, you will more likely watch it than one with only ten views. Usually, videos with ten views are not worth watching. Social media are prone to information cascades and herd behaviour. A hilarious cat video can become more popular because it is in favour already, while funnier cat videos may remain unnoticed. Stock market bubbles also work in this fashion.

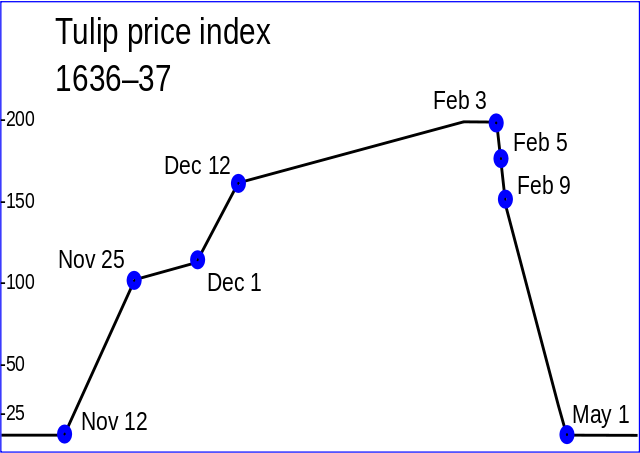

During the Dot-com bubble, investors piled on Internet stocks. Investors knew these stocks had no value but bought them anyway because they rose. Groupthink can lead to mass delusions like stock market bubbles. In 1841, Charles Mackay wrote about three financial manias, John Law’s Mississippi Scheme, the South Sea Bubble, and Tulipomania. He argued that greed and fear drive financial markets and can make people act irrationally.3

Information cascades can lead to mass delusions because of confident but mistaken people. Self-assured people aren’t always wrong, but when they are, they amplify their errors. During the Dot-com bubble, the loudest voices on Internet message boards boasted about their profits in Internet stocks. The quality of group decisions depends on how we aggregate information. To use collective intelligence, we should try to:

- make people feel free to come forward with their information and opinions;

- prevent groupthink or group members becoming biased by the information or opinions of others;

- focus on underlying causes rather than incidents.

Large groups have trouble solving collective action problems because those who don’t contribute benefit from the group effort while enjoying the advantages of not contributing. If they can get away with it, that undermines the group morale. We don’t experience the future now, so a future catastrophe appears hypothetical until it materialises. We likely underestimate its severity and delude ourselves, thinking it will not be so bad. And so, we take inadequate action. With challenges like global warming, it is unlikely the wisdom of crowds prevails. In this case, humanity acts more stupidly than most individuals would, so we might be better off with a dictator.

If you like this story, you might want to see this video:

Featured image: Tulip price index from 1636-1637. JayHenry (2008). CC BY 2.0. Wikimedia Commons.

Latest revision: 16 March 2024

1. Collective Stupidity – How Can We Avoid It. Sabine Hossenfelder. YouTube.

2. The Wisdom of Crowds. James Surowiecki (2004). Doubleday, Anchor.

3. Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. Charles Mackay (1841). Richard Bentley, London.