The last day

Imagine there is a lake in a distant forest. A plant grows on the surface. Its leaves suffocate all life below. This plant has already been there for 1,000 days. It doubles in size every day. So, here is a question. If the lake is already covered half by the plant, how many days are left to save the lake? The correct answer is one day.

Behold the power of exponential growth. The plant doubles in size each day. And so, it covers the entire lake tomorrow. It does not matter how long it has been there. It stops growing once there is no more room. As soon as the lake is fully covered, life in the lake ends. And if the plant depends on that life, it will die too.

The lake represents the Earth, the plant represents humanity, and the leaves are people like you and me. No more room for growth could mean mass starvation. As of 1971, humans use more of Earth’s resources than nature can replenish. Currently, we use nearly two times as much. By 2050, we need three Earths if we go on as we do.

There is only one Earth, so that is not going to happen. Make no mistake. We live on the proverbial last day. It does not matter how long humans have roamed this planet already. The Great Collapse is upon us. In 1972, a group of scientists in the Club of Rome ran a computer programme that predicted the end of civilisation as we know it when natural resources would run out shortly after the year 2000.1

These scientists set one of their best computers to work. And using the finest graphics available in the early 1970s, they made a scary diagram. It says doom is upon us. Human civilisation is about to collapse. The end times could be now.

Lessons of history

Societies and civilisations collapsed in the past, so history might teach us something about what awaits us. Theories about collapse are controversial, which means there often is no definite proof, and different explanations are possible. Whereas the debates between the experts are still raging, time is running out. Collapse is coming. Given what is at stake, we should heed the lessons from history in the best possible way, even when the evidence is inconclusive. When we draw conclusions from the information we have now, they may later prove to be incorrect. But we do not know that now, so we can only draw logical conclusions from what we know and act accordingly.

The fall of the Western Roman Empire is an example of a collapse. In the second century AD, diseases reduced the Roman population, eroding the tax base of the empire. The empire had a long border to defend, so emperors became increasingly desperate for revenues to finance the military. Over time, taxes and measures to ward off invasions became intolerable for Roman citizens, and the Western Roman Empire broke down. Most Romans were better off with a simpler life under the rule of Barbarians.2 The Eastern Roman Empire was more populous and did not collapse but lasted for another 1,000 years.

More often, collapses did not end well, and many people perished. That is why we dread collapse. The Western Roman Empire was underpopulated, and the state had become more of a burden than a help to its citizens. Other states supported their populace, so other breakdowns were more devastating, for instance, the end of the Mayan civilisation. The Mayans ran into the limits of their environment. State control over the economy had led to greater efficiency in the production and distribution of food, leading to larger populations. But the measures to increase food production stretched their environment to the breaking point, and improving agricultural output became increasingly difficult.1

The Mayan states then reverted to warfare to plunder each other’s crops. That made it even harder to maintain agricultural output, so the Mayans weakened from malnourishment and warfare. With their populations exhausted, the Mayan states collapsed together. In the short term, the peasants were better off as they did not have to pay taxes to support a state. In the long run, with irrigation works and granaries abandoned and defences neglected, agricultural output collapsed too, and population numbers dropped by 90%.2 Had the Mayans not waged wars but cooperated peacefully to reduce population instead, their civilisation could have declined more gracefully.

Underlying causes

Jared Diamond sees five contributing factors to past collapses: climate change, hostile neighbours, the loss of essential trading partners, environmental problems, and society’s response to these challenges. The underlying cause is often overpopulation relative to the number of people the environment can handle.3 That is true for the Mayans but not the Romans. The Romans had hostile neighbours but not overpopulation. Higher population numbers could have helped the empire to survive.

Tainter argues that in both cases, the costs of the state exceeded the benefits. Due to underpopulation in the Western Roman Empire, the few people that paid taxes could not afford them. The Mayan states organised agricultural production. At some point, the Mayans were out of options to improve agricultural production, and more state interference did not produce more crops or better management of surpluses and deficits. Overpopulation or overstretching the environment puts a premium on organising, but it postpones the inevitable and makes the collapse worse. Had the Mayans not organised themselves in states, there would have been no overpopulation, and fewer people would have died.

Our predicament looks more like that of the Mayans than the Romans. Competition between states for resources may intensify, and the collapse could be brutal. Simplification and having fewer children is a way out, and we may be better off if we cooperate and reduce our populations gracefully. Ending the competition between states is paramount because power, for instance, a large economy, population and military, requires resources and energy. If one state pursues that course, others must do that too.

In times of decline, even the best leaders look bad. They can only make things less lamentable than they otherwise would have been. As we notice the deterioration but do not experience the alternative, anger and frustration can take over, and people will look for scapegoats. Managing collapse and turning it into a more graceful simplification seems the best option. That requires the conviction of the general public. And it requires leaders with the authority to implement the necessary measures. The majority must stand behind these measures and force others to comply. It is about the survival of humankind.

Organising to solve problems

Tainter turns societal collapse into an economic calculation. In other words, he claims societies and civilisations collapse when the cost of their institutions exceeds the benefits. For instance, if the soil becomes depleted due to overuse, measures to improve crop yields or manage surpluses and deficits become increasingly expensive and have lower returns. The Mayans did not make these calculations by keeping ledgers of incomes and expenses. At some point, their measures became pointless. People were starving anyway. There is an upside to Tainter’s view, and that is why it should take the central stage. If we intend to decline gracefully, an economic approach is probably the most helpful way to do it, for instance, by including the cost of preventing or repairing the environmental damage in the price of products we buy or implementing flexible electricity pricing depending on the availability of solar and wind.

We organise ourselves in states and corporations to solve problems. For instance, we have police to solve a security problem. Complex organisations, like states or corporations, come with costs and benefits. When societies are simple, the expenses are low, while the benefits can be substantial. An elementary doctor’s post in the jungle might lengthen the life of local tribespeople by as much as twenty years. As the level of organisation increases, the price of additional complexity increases while the benefits decrease. And at some point, the costs might exceed the benefits. For instance, replacing the doctor’s post with a hospital that costs five times as much might add another three years to the life of the local inhabitants, but the costs might not be affordable. Perhaps, five tribes together could pay for the hospital. In complex societies, many tasks require occupational specialisation, information processing and management. There are benefits to complex organisations, but they usually come with scale. Physicians who specialise can do better jobs when enough people share the costs.

Since the Industrial Revolution, markets and energy usage expanded. Abundant fossil fuels and increases in scale have reduced the cost of organisation. And so, the benefits outweigh the expenses at a much higher level than before, allowing us to specialise further than before. In the past, over 90% of the people worked in agriculture, tilling the land. Now machines do that work, freeing up labour for other purposes. The same happened in the production of other goods and services. Technological development also increased benefits. For instance, computing power uses far less energy than forty years ago, making more uses feasible. As a result, we use far more energy for information technology than forty years ago. And we did not need that at all in the 1970s. It is a paradox we see often. When technology becomes more efficient and cheaper, we use much more of it and consume far more resources and energy. And so, efficiency improvements alone will not solve our problems. Once resource and energy supplies dwindle, the costs rise, and much of what we do now will lose its purpose, just like what happened to the Mayans. On the other hand, technological advances allow us to do much more with the same resources and energy, so the future will not be like the past.

Diminishing returns: an example

We have medical treatments that did not exist a century ago. As a result, life expectancy in the UK rose from forty to eighty years between 1860 and 2020. Today, the costs can exceed the benefits, and complexity can become a burden to the population at large. An example can illustrate this. Cuba is poor compared to the United States, and many essentials are hard to come by. Cuba only has rudimentary healthcare, but it is available to everyone, while the United States spends more on healthcare than any other nation. Yet, life expectancies in Cuba and the United States are similar, despite the US having the best doctors and the most advanced treatments. We should not be surprised because an elementary doctor’s post delivers more value for money than a more complex hospital. And lifestyle affects life expectancy as well.

In most other developed countries, people live longer than in the United States and at lower costs. Cuban healthcare gives value for money because it is simple and equally distributed. Healthcare in the United States performs poorly because it is burdened with litigation, while pharmaceutical corporations and medical professionals enjoy privileges they do not have in other countries. And healthcare is not equally available to everyone. And Americans may live less healthily than Cubans. Obesity, homicides, opioid overdoses, suicides, road accidents, and infant deaths come into the picture. Americans use drugs, eat fast food and drink sodas unavailable in Cuba. Indeed, the death toll from drugs, fast food and sodas in the United States may exceed that of famines in Cuba. Americans may experience more stress as workers than Cubans because they need to be competitive in a market economy that is constantly economising and improving efficiency. As a result, Americans may die of heart disease and drug use. Most Americans may be better off with a simpler life.

If you grow your own food, and your neighbours help you build your home, nothing gets added to GDP. Eating fast food, drinking sodas and being treated for obesity and other diet-related illnesses are good for profits and economic growth, as is working hard and taking drugs or seeing a psychiatrist for stress symptoms. Sodas, treatments for obesity, medication and therapeutic sessions all add to GDP. Economists call it wealth creation. It may help to explain why America is wealthy. In the United States, a small group of politically connected big corporations and specialists make lots of money, for instance, lawyers, pharmaceutical corporations and medical specialists. In complex societies, highly trained professionals earn much more than ordinary people. But their value to society can be below zero if you account for the costs. Just imagine how much cheaper things become if you eliminate the lawyers and the litigation. And think of what it will do to GDP. In other words, you might be better off poorer.

Managing excess

Excessive production and consumption create problems we must manage. That requires specialisms, controls, and the like, and that becomes increasingly costly. Complexity and specialisation suffer from diminishing marginal returns. The costs increase while the benefits decline. Consider the issues of food production and pollution control. According to Tainter, increasing world food production by 34% between 1951 and 1966 required increasing expenditures on tractors by 63%, fertilisers by 146%, and pesticides by 300%. And we now have to deal with soil degradation, which endangers our future food production.

Pollution control shows a similar pattern. For instance, removing all organic waste from a sugar processing plant costs 100 times more than removing 30%. Reducing sulphur dioxide in the air of a US city by 9.6 times or particulates by 3.1 times raises the cost by 520 times. These numbers may be outdated, but the nature of the problem remains the same. Allocating more resources to R&D can give a temporary respite from diminishing returns. But R&D also has diminishing returns.2 We might increase food production or contain pollution, but it can become prohibitively expensive.

Like the Mayans, we have stretched our agricultural lands to their limits. New technology and control measures will probably only postpone the inevitable. We must consume less and have fewer children. We can do without many things, or we can produce things differently. And having fewer children gives the remaining children a better life. Stable supplies of large quantities of fossil fuels sustain our current complex civilisation. Unstable supplies of renewable energy can drive the simplification. If we compensate for carbon emissions, fossil fuels become expensive, and it can be economical to reduce energy consumption or rely on renewable sources. As a result, pressures can mount to decentralise and live simpler.

Simple living means depending more on communities and less on markets and states. Local production replaces long-distance trade. To which degree that will happen, no one can tell. After a graceful simplification, energy supply, wealth and complexity will remain well above the levels seen for most of history. If we manage the collapse well, we likely are better off than we would have been otherwise. But we will live and organise ourselves differently than in the past. And our lives can be agreeable. The 80/20 rule states that 20% of the causes have 80% of the effects. Our well-being might decline by 20% when we reduce resource and energy consumption by 80% if it is the wealthiest who make the sacrifice. And that is some good news at last.

Latest revision: 8 July 2023

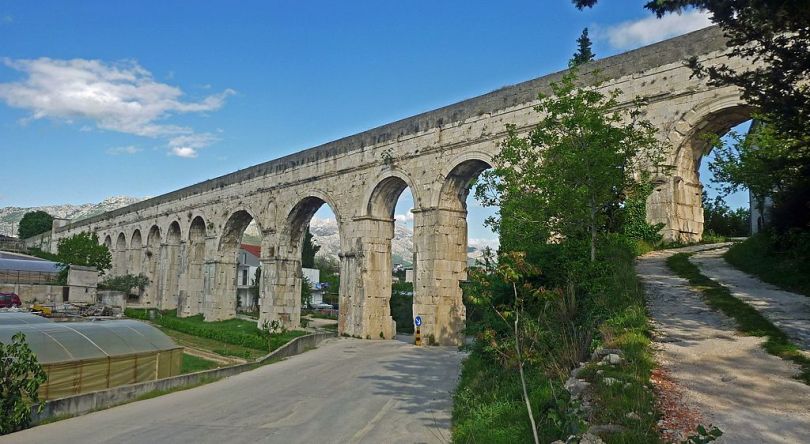

Featured image: Diocletian’s Aqueduct in Split, Croatia, built around 300 AD. User: SchiDD. Wikimedia Commons.

1. The Limits to Growth. Donella H. Meadows, Dennis L. Meadows, Jørgen Randers, William W. Behrens III (1972). Potomac Associates – Universe Books.

2. The Collapse of Complex Societies. Joseph Tainter (1988). Cambridge University Press.

3. Collapse: How societies choose to fail or survive. Jared Diamond (2005). Viking Press.