Introducing Chief Inspector Jacques Clouseau

In the autumn of 1989, I was a student and forced to leave a dormitory because I was immature and didn’t fit in. Most notably, I couldn’t get along with a particular Lady. I returned to my parental home to gather courage before trying out another dormitory. There was not much to laugh about in those days, except for a few episodes of Chief Inspector Jacques Clouseau on German television. My parents lived near the German border, so I could watch them. The German dubbing was as funny as the original.

Clouseau was inept, but he always managed to solve the mystery. Guided by a few hunches and vague clues that only made sense to him, he ignored the obvious explanations of the facts and uncovered the truth by accident. So, how could a bumbling clown like Clouseau be correct while the competent fail? The answer is that he is a fictional character in a story. The plot is that Clouseau is right in the end.

History is Her story, and the pun may be intentional. Apart from women in the Bible, God played other roles. How can we know who they were? That is where Clouseau comes in. We live in virtual reality, so this can be a story with a plot. I could be right if that is the plot of the story. My investigation produced a list of possible avatars of God. It has gaps and overlaps. God may have skipped the childhood years of the avatars She chose. The Lady at the dormitory is one of them. That, I found out nineteen years later.

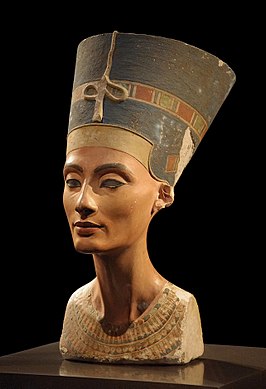

Akhenaten and Nefertiti

As far as we know, the Egyptian Pharaoh Akhenaten and his wife, Nefertiti (1370-1330 BC), were the first monotheists. They promoted the worship of a single deity, a sun disk named Aten, and ordered the end of worship to other gods. In doing so, they broke with the Egyptian religious tradition. Nefertiti may have been an avatar of God. Worshipping the Sun makes sense. Just imagine the Sun doesn’t come back in the morning. You can better ensure he does and sacrifice a bull every evening before sunset. Their new religion didn’t last. After their reign, traditional beliefs returned. They were too far ahead of their time.

Cassandane

Cyrus the Great was a Persian Emperor and one of the first multicultural rulers. He respected the customs and religions of the lands he conquered. That made it easier for him to rule such a large empire. Otherwise, he had to assimilate all the people in his realm into Persian culture, which would have distracted him from making more conquests. And by the way, people didn’t mingle as much as they do today, so cultural differences didn’t cause that much trouble. Cyrus the Great was a prominent figure in history. Iranians still call him The Father. Most Iranians aren’t Christians, so that doesn’t confuse them.

Cyrus also conquered Babylon. The Jews in exile caused trouble with their Zionism there, so Cyrus sent them back to Israel and gave them money to rebuild their temple. The Jews were grateful and considered him a Messiah. The fate of a Messiah is to be married to God, so his wife, Cassandane (567-537 BC), could have been God in disguise. Cyrus and Cassandane loved each other deeply, according to the historical records. Cyrus would not have been a proper Messiah in the biblical sense if a woman had not sealed his fate. Accounts of Cyrus’ demise and death diverge, but that fact is beyond dispute.

The Greek historian Herodotus noted that he died in a battle with the Massagetae, a fearsome steppe people who lived in what is now Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan. To acquire the territory, Cyrus first sent an offer to marry their ruler, Queen Tomyris, a proposal she rejected. He then tried to take the Massagetae territory by military means. Tomyris challenged him to meet her forces in honourable warfare. Learning that the Massagetae were unfamiliar with wine and its intoxicating effects, Cyrus set up a poorly defended camp with plenty of it and left with his best soldiers.

The general of Tomyris’s army, her son Spargapises, overran the camp with his troops. They got drunk, and Cyrus defeated them in a surprise attack and captured Spargapises, who then committed suicide. Tomyris then vowed revenge, leading a second wave of troops herself. Cyrus’ forces suffered massive casualties, and he also died. Tomyris ordered the body of Cyrus brought to her, then decapitated him and dipped his head in a vessel of blood. Accounts on the matter differ, and Herodotus offers us the most colourful account, but others confirm the death of Cyrus at the hands of Tomyris.

Olympias, mother of Alexander the Great

Olympias (376-316 BC) was the mother of Alexander the Great. Alexander’s lasting legacy is the spread of Greek culture in the Mediterranean. Greek thought and culture later influenced Judaism and Christianity. The Word would never have become flesh without Platonic philosophy. And Christians could never be born of God, the Father, without the influence of Greek mythology. You can see how God works in ways we can’t anticipate. Olympias, who was married to King Philip II of Macedonia, claimed that Alexander was the son of Zeus, the supreme god of the Greeks.

According to the Greek historian Plutarch, Olympias had a dream in which a thunderbolt struck her womb on the eve of her marriage to Philip. Philip was said to have seen himself in a dream sealing up his wife’s womb with a seal. A virgin birth it was, or it could have been. Plutarch offered several interpretations of these dreams, for example, that Alexander’s father was Zeus, the supreme deity of the Greeks. That would have made Alexander the Son of God. And so, Olympias might have been an avatar of God.

Philip chose Aristotle as Alexander’s tutor. Alexander and Philip fought battles together and defeated Thebes and Athens, making Macedonia the dominant power in Greece. They then began to plan an invasion of Persia. Philip remarried, which threatened Alexander’s position as heir to the throne. A brawl at the wedding led to Olympias and Alexander going into exile. While attending the wedding of his daughter to Olympias’ brother, a captain of Philip’s bodyguards assassinated Philip. A possible conspirator was Olympias. The nobles and army immediately proclaimed Alexander King. In the subsequent years, Alexander conquered the Persian Empire and ventured into India. Alexander died young, at the age of thirty-two, possibly from poisoning.

Alexander the Great was one of the most successful conquerors in history. He became popular in the Mediterranean and the Middle East. Legends sprang up about his exploits and life, which had a profound impact on the Abrahamic religions. He is a significant figure in Judaism. The Christians in the Near East turned him into a saint. The Quran mentions him and recites scraps of the legends about him. Alexander supposedly travelled to the ends of the world to build a wall to keep Gog and Magog out of civilised lands. Alexander de Grote (Alexander the Great) was my classmate at primary school for several years, a remarkable coincidence. Perhaps his parents had a humorous fit when naming him.

Queen Dowager Zhao

Chinese emperors held the Mandate of Heaven. The Emperor was the Son of Heaven. The title legitimised the rule of the Emperor. In Chinese thinking, the gods didn’t play a central role. Thus, being the Son of Heaven was the closest to being divine. If insurgents overthrew an Emperor and installed a new one, the old emperor had lost the mandate, and the new Emperor had it instead. That is very pragmatic indeed. This arrangement also provided stability as it deterred potential contenders to the throne.

China’s first emperor was Qin Shi Huang. He unified China for the first time around 220 BC. He was a particularly ruthless person. He had to be because he came out on top after five centuries of relentless warfare that had no equal in history. His reign didn’t last. Qin Shi Huang died in 210 BC while on a trip to procure an elixir of immortality from Taoist magicians, who claimed the potion was stuck on an island guarded by a sea monster. Widespread revolts ended his son’s government shortly afterwards.

A new imperial dynasty soon established itself. Qin Shi Huang’s lasting legacy is not only the unification of China. He also standardised writing throughout the empire and introduced a pictural rather than a phonetic script so people could read the same documents everywhere in China, even when they spoke different languages. As a result, China could build its national identity around a set of writings. China’s identity never perished, even when the country fragmented and warlords temporarily took over.

Qin Shi Huang’s mother was Queen Dowager Zhao (280-228 BC), the wife of King Zhuangxiang of Qin. Queen Dowager Zhao was the daughter of a prominent family. She was a concubine of a merchant named Lü Buwei, who gave her to his protegé, Prince Yiren of Qin. Thanks to Lü’s intervention, Prince Yiren became the ruler of the Kingdom of Qin and King Zhuangxiang. His son Qin Shi Huang succeeded him. It may well be that Queen Dowager Zhao was God in disguise, adding some justification to the title of Her son, Son of Heaven.

When my son was nine, he jokingly referred to himself as the Emperor of China. He often ordered my wife and me. We were making a joke out of it and called him the king. Still, my son insisted he was the Emperor of China. ‘The Emperor of China demands cheese,’ he then added. An article about the first emperor of China appeared in a television magazine shortly after I found out we live in a virtual reality.

Cleopatra

Cleopatra (69-30 BC) was the last Pharaoh of Ancient Egypt. Few women have proved to be as strong a ruler as Cleopatra, even though She ultimately failed, causing Egypt to lose independence and become a Roman province. She presented Herself as a reincarnation of the Egyptian goddess Isis, who later, with her son Horus, became the template for the images of the Madonna with the child Jesus. Egyptian Pharaohs were deputies of the gods, but Cleopatra went further by claiming to be a goddess Herself.

Even Julius Caesar was impressed by Her personality. He abandoned his plans to conquer Egypt and backed Her claim to the throne. It is not a mere coincidence that Julius Caesar had the same initials as Jesus Christ, and that both died because of betrayal. After Caesar died, She supported her next lover, Mark Antony, in a power struggle with the future Emperor Augustus. That led to Cleopatra’s downfall and suicide. She was already looking forward to Her next role, Mary Magdalene, the wife of an obscure Jewish prophet who was to change world history.

Empress Theodora

Empress Theodora (490-548) was one of the most influential women in Roman history. An official of Her time noted that She was more intelligent than any man. Her husband, Emperor Justinian, realised this as well. He allowed Her to share his throne and take part in decision-making. She was a controversial figure. As a young woman, Theodora earned Her living as an actress, which meant entertaining men with indecent dances in establishments of dubious reputation, and possibly it included prostitution. Procopius’ Secret History, an ancient version of a gossip channel with a preference for slander, is the foremost source of information about Her early life, so we can’t be sure.

Later, Theodora travelled to North Africa as the concubine of Hecebolus, a Roman governor in Libya. Procopius alleged that Hecebolus mistreated Theodora, and their relationship ended in a quarrel. The then-destitute Theodora went to Egypt and converted to Miaphysite Christianity. Theodora later returned to Constantinople, where She met the future Emperor Justinian. Justinian was impressed by Her. He wed Theodora even though She already had an illegitimate daughter, which caused a scandal. And Justinian had to change the law to marry Her.

Theodora assisted Her husband in making decisions, plans, and political strategies, participated in state councils, and had a significant influence on him. She was an intimidating person who instilled fear, yet She feared no one. There was an uprising during their reign, and rioters set public buildings on fire and proclaimed a new emperor. Justinian and his officials discussed the situation and planned to flee, but Theodora spoke out against this plan. According to Procopius, Theodora interrupted the Emperor and his counsellors, saying,

My lords, the present occasion is too serious to allow me to follow the convention that a woman should not speak in a man’s council. Those whose interests are threatened by extreme danger should think only of the wisest course of action, not of conventions. In my opinion, flight is not the right course, even if it should bring us to safety. It is impossible for a person, having been born into this world, not to die; but for one who has reigned, it is intolerable to be a fugitive. May I never be deprived of this purple robe, and may I never see the day when those who meet me do not call me Empress. If you wish to save yourself, my lord, there is no difficulty. We are rich; over there is the sea, and yonder are the ships. Yet reflect for a moment whether, when you have once escaped to a place of security, you would not gladly exchange such safety for death. As for me, I agree with the adage, that ‘royal purple’ is the noblest shroud.1

Her powerful and inspiring speech convinced them to stay. Justinian then ordered his loyal troops to attack the demonstrators, resulting in the deaths of over 30,000 civilians. Some estimates put the death toll as high as 80,000. The corpses must have piled up on the streets of Constantinople. The reason was Her desire to wear a purple robe. After the revolt, Theodora and Justinian ordered the rebuilding of Constantinople. The works included aqueducts, bridges and churches, including the Hagia Sophia, which became one of the world’s architectural wonders.

Theodora participated in Justinian’s legal and spiritual reforms, was involved in women’s rights, and helped underprivileged women. She bought girls who had been sold into prostitution and freed them. She created a convent where former prostitutes could support themselves. Theodora even tried to eradicate prostitution. Theodora and Justinian expanded the rights of women in divorce and property ownership and instituted the death penalty for rape.

Procopius claimed these reforms made women morally depraved, as men could no longer beat and abuse them at will, which might be the reason why Procopius disliked Theodora. He had some other details about Her to share. According to him, the senators had to prostrate themselves whenever entering the Imperial couple’s presence,

Not even government officials could approach the Empress without expending much time and effort. They were treated like servants and kept waiting in a small, stuffy room for an endless time. After many days, some of them might at last be summoned, but going into her presence in great fear, they very quickly departed. They simply showed their respect by lying face down and touching the instep of each of her feet with their lips; there was no opportunity to speak or to make any request unless she told them to do so. The government officials had sunk into a slavish condition, and she was their slave-instructor.

That could be sixth-century gossip, but perhaps the almighty Owner of the magnificent city of Constantinople and the rest of the universe desired to be reminded of Her greatness before She went into the desolate Arab desert as Khadijah to go after Muhammad.

Empress Wu Zetian

After Khadijah had departed, another remarkable woman arrived on the scene. Empress Wu Zetian (624-705) was the only female ruler in China’s history and one of its most gifted Emperors. She ruled from 665 to 705, first as the consort of the incompetent Emperor Gaozong, then as the power behind the throne held by Her youngest son and from 690 as the sole Empress. Under Her reign, China’s power increased, the economy improved, and corruption in the imperial court declined. Notwithstanding those impressive feats, the traditionalist Confucianists called Her the Evil Empress. ‘She killed her sister, butchered her elder brothers, murdered the ruler, poisoned her mother,’ their chronicles say.2

It is doubtful that it is all true. A woman on the throne was against widely held misogynistic, traditional Chinese beliefs. Add to that that Wu’s reforms helped the peasants, so the elites weren’t all too pleased with them. There was no glass ceiling in those times preventing women from rising to the top. At the time, that ceiling was made of reinforced concrete. She must have been cunning and ruthless. Her rise to power is a story of intrigue the likes of which the world has not seen before, or afterwards.

Wu came from a wealthy family, and Her father encouraged Wu to read books and pursue an education that included politics, governmental affairs, writing, literature, and music. After being summoned to the palace to become a low-ranking concubine, Wu reportedly revealed ambitions to ‘meet the Emperor’ to Her mother. According to Her account, She once impressed Emperor Taizong with some tough talk,

Emperor Taizong had a horse named Lion Stallion, and it was so large and strong that no one could get on its back. I was a lady in waiting attending Emperor Taizong, and I suggested to him, ‘I only need three things to subordinate it: an iron whip, an iron hammer, and a sharp dagger. I will whip it with the iron whip. If it does not submit, I will hammer its head with the iron hammer. If it still does not submit, I will cut its throat with the dagger.’ Emperor Taizong praised my bravery.

After Emperor Taizong died, Gaozong became emperor at the age of twenty-one. He was inexperienced and frequently incapacitated by a sickness, causing spells of dizziness. His wife, Empress Wang, introduced Wu because Emperor Gaozong didn’t favour her but his concubine, Xiao. Wang was childless, while Xiao had borne him a son. Wang hoped Wu’s beauty would distract the emperor from Xiao. Wu soon overtook Xiao as Gaozong’s favourite. In 652, Wu gave birth to her first child, a son named Li Hong. In 653, She gave birth to another son.

Wu is infamous for the way She supposedly eliminated Wang and Xiao. As the story goes, Wu smothered Her week-old daughter, a child She had with Gaozong, and blamed the baby’s death on Wang, who was the last person to have held her. The emperor believed the story and imprisoned Wang. Xiao soon followed suit. Once She was empress, Wu ordered both women’s hands and feet lopped off and had their mutilated bodies tossed into a vat of wine, leaving them to drown.2 At least that is what the chronicles authored by Her political enemies tell us. It might be true, but it might not be.

In 655, at the age of 31, Wu became Gaozong’s empress consort and a powerful political force. She had considerable sway over the Emperor. From then on, Wu began to intimidate and eliminate Her opponents. One of the first things Wu did was to submit a petition. It praised the faithfulness of Han and Lai, who had opposed Her unprecedented rise to power. Her purpose was to inform them they had offended Her and that She was aware of their opposition. She knew the psychological tricks. Han offered to resign soon afterwards. After removing those who opposed Her rise, She had even more power, and Emperor Gaozong asked Her advice on petitions made by officials and state affairs.

Wu was more decisive and proactive than Her husband, who was often unwell and left decision-making to Her. Historians believe that Wu was the actual ruler for over 20 years during Gaozong’s reign. Her strong leadership and effective governance made China one of the world’s most powerful nations. Empress Wu had a network of spies in the royal court and throughout the empire. There were countless plots against Her.

She reformed the imperial examination system to encourage capable officials to work in the government. Wu eliminated real or perceived rivals to power through death, demotion, and exile. Her secret police took care of that. Wu’s measures were popular. She ensured that free, self-sufficient farmers could work their land, boosting the nation’s economy. She also helped the lower classes through relief.

Upon the death of her husband, Emperor Gaozong, Wu became Empress Dowager and Regent, gaining complete power. Wu poisoned the crown prince, Li Hong, and exiled other princes so that She could put Her son, Emperor Zhongzong, on the throne. Zhongzong was weak and incompetent like his father, so the new Empress Wei sought to place herself in the same position of authority that Empress Wu had enjoyed. Wu then deposed Emperor Zhongzong and placed another puppet on the throne for a while, before finally becoming the sole ruler of China in 690. She remained in power until She fell ill in 705, and a coup returned the throne to Her son Zhongzong. She died the same year.

Maria, daughter of Harald III of Norway

Harald Sigurdsson was the King of Norway from 1046 to 1066. As a young man, he had to flee Norway because he had backed his half-brother Olaf’s claim to the Norwegian throne and was defeated. He and his men went to Russia, where they served as soldiers of Yaroslav I the Wise. Later, they became mercenaries in the Byzantine Varangian Guard. Harald became commander of the Varangian Guard and was involved in the imperial dynastic disputes. Harald spent time in prison because of palace intrigue. In 1042, he requested to leave, but the Empress refused. He escaped and returned to Russia, where he prepared his campaign to claim the Norwegian throne for himself. The Chronicle of the Kings of Norway Saga of Harald Hardrade mentions,

There was a young and beautiful girl called Maria, a brother’s daughter of the Empress, Zoe, and Harald had paid his addresses to her, but the Empress had given him a refusal.

Based on the saga, Michael Ennis wrote a novel, Byzantium, where he speculated about a passionate love affair between Maria and Harald, of which Ennis vividly describes the details. They tried to flee Constantinople together. They ran into a Russian fleet that attacked the city. Maria died, but Harald escaped. The accounts of what transpired diverged, and Ennis filled in the gaps with his imagination. In 1046, Harald returned to Norway and took the throne. On his way back, he stayed in Russia and married Elisiv, a daughter of Yaroslav I. I always had an interest in the Byzantine Empire. That made me read the novel. As I don’t read many books, it is noteworthy.

After failing to conquer Denmark, Harald set his eyes on England. There, he died during the invasion of the country in 1066 AD. His demise is part of a coincidental scheme related to D-Day, as mentioned in The Virtual Universe. Harald’s daughter Maria died on the same day in Norway, a remarkable coincidence. In his book, Ennis speculates that Maria was the reincarnation of Harald’s former lover, who wanted to be with him. She dropped dead when he died. Ordinary people can’t reincarnate into whom they desire or drop dead at the time of their choosing. And so, Maria could have been God. The Finnish band Turisas dedicated a song named ‘The Great Escape’ to Harald, a noteworthy coincidence.

Hildegard von Bingen

Hildegard von Bingen (1098-1179) was a German Benedictine abbess and an active writer, composer, philosopher, mystic, visionary, and medical writer and practitioner. There are more surviving chants by Von Bingen than by any other composer from the entire Middle Ages. She is also one of the few known composers who wrote both the music and the words. She corresponded with popes, heads of state and emperors. She travelled often during preaching tours. Abbots and abbesses sought the prayers and opinions of Von Bingen on various matters.

Hildegard von Bingen claimed to have had visions as a little child, seeing all things in the light of God through the five senses: sight, hearing, taste, smell, and touch. Based on these experiences, Hildegard of Bingen wrote three books on visionary theology. She also wrote extensively about medicine from practical experience. She spoke out against corrupting church practices such as simony.

In her works, Hildegard von Bingen held a deviant perspective on Eve’s role in the Fall. She highlights Eve’s mother-bearing qualities, stressing her role as the mother of humankind. She further wrote, ‘Woman may be made from man, but no man can be made without a woman.’ It refers to the story in Genesis, and the remark may have been a hint that it was illogical in an era when you couldn’t say that plainly. While promoting chastity, Von Bingen was the author of the first known description of the female orgasm,

When a woman is making love with a man, a sense of heat in her brain, which brings with it sensual delight, communicates the taste of that delight during the act and summons forth the emission of the man’s seed. And when the seed has fallen into its place, that vehement heat descending from her brain draws the seed to itself and holds it, and soon the woman’s sexual organs contract, and all the parts that are ready to open up during the time of menstruation now close, in the same way as a strong man can hold something enclosed in his fist.

The lively description suggests, not only first-hand knowledge Von Bingen should not have acquired during Her lifetime as a nun, but also a lack of shame comparable to Eve. And, according to Von Bingen, Adam had a pure voice. He joined the angels in singing praises to God before the Fall. That is also knowledge Von Bingen could not have acquired during Her lifetime. She either made it up or was present when it happened. If She had been Eve, She was there. Around the time Von Bingen lived, an anonymous monk in the Netherlands wrote down the oldest known written sentence in the Dutch language,

hebban olla uogala nestas hagunnan hinase hic anda thu uuat unbidan uue nu.

The English translation is, ‘Have all birds started nests except me and you. Do we start now?’ A teacher at my primary school told the class about this text. The lines remained in my mind. Later, I imagined a Gregorian chant based on these words when Sadeness from Enigma was often on the radio. These lines intrigued me for no apparent reason, it seemed at the time, and I now suspect that the monk had Hildegard von Bingen in mind. Did they meet? It seems unlikely. Perhaps, he had a vision of Her.

Joan of Arc

In 1429, the situation was desperate. There was no hope for France. The English and their ally, Burgundy, had overrun most of France. Only a small pocket of resistance remained. It is not the start of an episode of Asterix & Obelix, but the story of Joan of Arc (1412-1431). She started as an uneducated peasant girl from Domrémy, an obscure village in Northern France and became a military leader who changed the course of history. After years of defeats, the leadership of France had been demoralised and discredited.

The seventeen-year-old Joan joined a relief army to end the siege of Orléans. She arrived at the city in April 1429, wielding Her banner and bringing hope to the demoralised French army. Nine days after her arrival, the English abandoned the siege. Joan encouraged the French to aggressively pursue the English, which led to another decisive victory at Patay, opening the way for the French army to advance on Reims, where the French crowned their new King with Joan at his side.

But fortunes changed. After the coronation, Joan participated in the unsuccessful siege of Paris in September 1429 and the failed siege of La Charité in November. In early 1430, Joan organised a company of volunteers to relieve Compiègne, which the Burgundians had been besieging. There, Burgundian troops captured Joan. She tried to escape, but the Burgundians handed Her to the English. The English put Joan on trial and burned Her at the stake as a witch.

Joan of Arc led the French army to several crucial victories that boosted French morale and changed the course of the war. She claimed to have divine guidance. Modern scholars try to explain Joan’s visions as delusions, like they usually do, but documents from that time indicate Joan was healthy and sane. She was only nineteen when She died. In the decades that followed, France prevailed. Was She God in disguise? Probably so..

Latest revision: 31 January 2026

Featured image: Roman sculpture of Cleopatra wearing a royal diadem. Altes Museum in Germany. Wikipedia. Public Domain.

1. Lend Me Your Ears: Great Speeches in History. William Safire (2004). Rosetta Books.

2. The Demonisation of Empress Wu. Mike Dash (2012). Smithsonian.