The collapse of complex societies

In today’s globalised economy, imports and exports account for 40-60% of most nations’ GDP, so nearly every country has integrated into the world economy. That may change if the world economy collapses. A possible cause is a sudden loss of confidence in the US dollar, which is the world’s reserve and trade currency. A collapse of the world economy may trigger a reduction in complexity, commonly referred to as the collapse of world civilisation. Such a scenario is plausible, so it is prudent to plan for it. Perhaps, we can rebuild our civilisation with local initiatives. Usually, a collapse is involuntary. Things fall apart, not because we want to, but because we can’t afford our lifestyles anymore.

In ‘The Collapse of Complex Societies,’ Joseph Tainter argues that collapse is a sudden loss of complexity because the cost of complexity outstrips its benefits, leaving us better off with simpler lives. If you can’t afford food, life can be better without mortgages, taxes, medical bills, tuition costs, and most other things you buy if it means that you have something to eat. It is not that housing, government, education, and businesses have no use. After all, complexity solves problems. Still, we could do with less, accept life as it is, and lead agreeable lives without social media and new treatments for cancer. It may seem disagreeable, but the Amish are content with that lifestyle. And we may have to.

In such situations, communities and families take on a greater role at the expense of markets and states. Village life in the past wasn’t ideal. Abusive parents could do as they pleased and get away with it. The state didn’t interfere. And if you were gay, you had better not tell. Today, the idea of community has changed. You can set up a community with like-minded people. And there has been some progress in the degree of diversity people accept, so you may not have to. Collapse means that states and markets retreat, even though the degree to which they will is unknown at present. Ideally, self-sufficiency and widely agreed-on moral values will fill in the void, but we will not return to the dark ages.

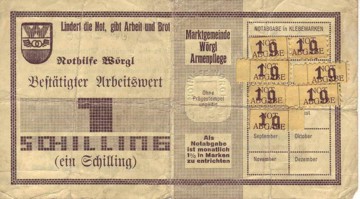

Perhaps we can learn to live in harmony with one another and with nature. That is unlikely to happen, unless a new world religion emerges. Another requirement is breaking free from the stranglehold of usury and trade. Local money enabled Wörgl to achieve some economic independence by keeping money circulating within the local economy and encouraging townspeople to buy local products. When you use regular money, such as the euro, you can buy on international markets. The money will leave the local economy and may end up on the other side of the world. You don’t know what your money will do there. It might facilitate drug trades or child labour.

Breaking free from markets

Today, there are thousands of local and regional vouchers, but few were as successful as the Wörgl scrip. One notable exception was the Red Global de Clubes de Trueque (Global Network of Barter Clubs) during the Argentine Great Depression of 1998-2002. It was an even more spectacular success. The network emerged from local initiatives following the collapse of the Argentine banking system, enabling millions to exchange goods and services using local vouchers called créditos. Argentinians lacked a reliable medium of exchange, so barter clubs, which had initially been a lifeline for the unemployed, eventually helped a significant portion of the middle class, many businesses, and some factories.

You can see the role of usury and international trade and finance in these crises. In Wörgl, a holding fee on money brought the local economy back to life, indicating that the global economy required negative interest rates, which were impossible in a usury-based financial system. To maintain a stable currency for their payments, the Argentinians could have borrowed US dollars in global markets. Due to Argentina’s creditworthiness, it could only do so at a high interest rate, which would have further eroded the country’s finances. The Argentinians would have used these US dollars to purchase foreign goods on international markets, leaving the Argentinians soon without a means of payment again.

Had Argentina been a closed economy that had only bartered with the outside world, the crisis wouldn’t have happened. That is only hard to carry out. Traders would undermine the scheme by smuggling marketable goods in and out of the country. Only a few totalitarian regimes, like Nazi Germany, succeeded in doing this. Still, the thought experiment of a closed economy explains why barter clubs were successful. And it partly explains the economic miracle of Nazi Germany. The Argentinians participating in the barter clubs had nothing to offer to international markets. Or, they supported the clubs to help their communities and were willing to forego better deals available in global markets.

Limitations

Amid a worsening depression, the Wörgl economy improved, and unemployment dropped. Wörgl achieved this by breaking free from usury and the market. The Argentinian network of barter clubs also did. And there lies a significant issue. Modern economies utilise goods and services that require a scale that only larger markets or global initiatives can provide. One of them is finance. It is probably impossible to develop local financial markets for scrip, let alone make them usury-free. The options for spreading risks in small markets are limited. The day you can go to the bank to get a mortgage in local scrip may never come.

The initiatives were successful because of an emergency. There was a lack of a reliable medium of exchange. The Argentinian barter vouchers weren’t legal tender and had no backing of a national currency. Millions of people joined the network, but it declined after 2001. The network had no organised structure. There were thousands of barter clubs in the network, each with its own notes. The clubs accepted each other’s vouchers, so some clubs committed fraud by printing additional vouchers. The Argentinian economy recovered in 2002, so the need for the barter clubs also diminished.

Whether the local or regional money is a currency or a voucher depends on the setup. An exchangeable government currency inspires trust. Most initiatives issue vouchers, but some have a currency reserve backing them. Most are private, and the money is hardly ever legal tender. Typically, these initiatives have a specific goal, such as strengthening the local community or economy. The money issued by the Austrian town of Wörgl was as close to a currency as local money can get. A government issued it, accepted it for tax payments, and guaranteed the exchange rate with the regular currency.

The Wörgl scrip and the Argentinian barter clubs demonstrate that local currencies and vouchers can succeed in times of crisis when the circular money flows have collapsed, either due to deflation (leading people to hoard money) or inflation (making the country’s currency worthless). It is also possible to integrate these local economies into a larger economy through these monetary exchanges. However, when the economy is doing well and the circular flows are functioning, the role of these monies becomes marginal. And so, they complement the regular financial system and are complementary currencies.

If you can receive internationally accepted currency, such as euros, you prefer them to barter vouchers because they inspire more trust. In times of crisis, you may be willing to take less trustworthy money if that is the only one available. It will be impossible to have a global network of local vouchers. Money operates in a hierarchy of trust. Exchangeability in a regular currency makes them more trustworthy. Imagine that there are 1,000,000 barter clubs issuing vouchers worldwide. How can you know that a note is genuine, and, if so, that the club issuing it is not scamming the system? And so, a voucher or currency can best only circulate in the area where everyone knows it.

Credit means trust, and as a Dutch proverb says, trust comes on foot and leaves on horseback. It is hard to build, but easy to lose. There are always individuals trying to scam the system. The human desire to live off the work of others is eternal. It is the foundation of capitalism, as it is what investors seek to do. And people try to use the government for their gain by demanding benefits, favourable regulations, or lower taxes. It is also a reason why trade and usury exist, not the only one, of course, but it is good to keep this in mind. The Greek god of the merchants was also the god of the thieves. It is a cynical view, as most people are honest, but systems of trust are often as strong as their weakest link.

A local economy typically offers fewer choices and often poorer-quality products than international markets. You may accept these drawbacks to support your local community, since the best deal in the market may not be the best deal for your village or country. Walmart might be cheaper and offer a wider variety of choices, but buying at Walmart comes at the expense of local stores, factories, and suppliers, so that if you buy at Walmart, your sister or neighbour ends up unemployed and must move to the city to find a telesales job in the bullshit economy.

Making it work

Imagine that everyone does something helpful rather than wasting energy and resources in the bullshit economy, that no one is on the dole, and that people with limited abilities contribute what they can. Imagine that we respect nature and that the economy is sustainable. That might be possible when we end the dictatorship of usury and markets. In that case, we may work only twenty hours per week, have enough to live on, and can do as we please for the remainder of our time. Okay, we can’t visit Disney World or watch Formula 1 car racing, which are senseless, wasteful activities, so we must entertain ourselves with other things, like playing soccer or singing in a choir.

Since 1934, Switzerland has had a business-to-business barter cooperative, WIR, which issues credit, the WIR franc backed by assets the members have pledged in collateral. Businesses trade goods and services without using cash, allowing them to work with less financial capital, clear excess inventory, and build new business relationships. The United States has several barter organisations with varying credibility. Most are for-profit, so serving a community is not their primary objective.

Another scheme that can strengthen the local community is the Farmer-Citizens Initiative, also known as the Pergola Association. The market for agricultural produce is competitive, subjecting farmers to international finance and global markets. Farmer-citizens’ initiatives have varying setups. Usually, citizens pay a subscription fee to cover the farm’s expenses in exchange for a share of the produce. It enables farms to diversify and offer a broader range of food products. Rather than exploiting immigrants, farmers may hire locals to do chores. That is possible because these farmers don’t produce for global markets. The transactions can be in local scrip.

Government support can help. The Wörgl municipality accepted its currency for tax payments. Complementary currencies are not a recent invention. Accepting a currency as payment for taxes, or even requiring payment in that currency, has been a way for governments to generate demand for it, allowing them to issue currency without backing it in precious metals. In England, tally-stick money circulated within the country, as it had value only there, allowing local state money to coexist alongside the merchant’s money, gold coin, insulating the nation’s economy from the whims of international trade.

In a Natural Money financial system, local governments, such as municipalities, can issue local and regional currencies backed by national currencies or the global reserve currency (GRC), which are debts of national governments or the world government in the International Currency Unit (ICU). In a more decentralised world with a uniform law system, nation-states aren’t the highest authority. They, however, issue debts in the ICU, so there can be national currencies based on these debts. Municipalities can issue debts in the ICU. Using them as backing for local currencies makes maintaining parity with the national currency a challenge. And so, a full backing is of the essence.

To end usury and have lending, you not only need trust, but also efficient financial markets. Interest rates below zero can only exist when lenders expect repayment and the currency to have a stable value. In a small community, there are few lenders and borrowers, resulting in limited options. Raising capital for a new business or a mortgage in a local currency is probably impossible. And if a single business fails, a small bank can get into trouble. In larger financial markets, banks can diversify their investments.

Local monies are complementary, supplementing the regular financial system rather than replacing it. Preferably, their value stays on par with the regular currency. Only a full backing like in Wörgl can guarantee that. Small-scale lending and borrowing in these currencies based on personal trust is possible. It is not feasible to develop financial markets in them. Still, in a future where communities become increasingly self-sufficient, complementary currencies will play a more significant role than they do today.

To make it work, we should have motives beyond securing the best deal or maximising profit. So far, these other motives haven’t moved mountains. That is because only faith can. Money gives us a false sense of security. It promises us that we can buy anything we want, at any time we want. But money is not a basement full of foodstuffs or safety to walk the streets. Once we have ruined this planet and society falls apart, we will find out. Still, we put our faith in money. If it is not the euro, we put our faith in gold and silver rather than our communities. That is because trade and usury have destroyed them.

Latest revision: 12 November 2025

Featured image: Wörgl bank note with stamps. Public Domain.