Strikingly different

The Gospel of John is strikingly distinct from the other Gospels. In Mark, Matthew, and Luke, Jesus appears human, yet enigmatic. In the Gospel of John, he appears godlike. The Gospel of John is more recent than the other Gospels, and biblical scholars believe Christians had deified Jesus by that time. There is a problem with this reasoning. Some Christians worshipped Jesus as a godlike creature early on. In the Epistle to the Philippians, Paul cites a poem stating Jesus is in the form of God (Philippians 2:6-11). Scholars believe it is an older poem, dating back to the earliest days of Christianity.1 Maybe. Paul was a creative genius, and he made up a lot of things, perhaps nearly everything he wrote.

Other scholars believe that there once was a separate Johannine community in Syria, with the Gospel of John and the letters of John serving as its scriptures. The Johannine writings use the phrase ‘born of God,’ suggesting that God is a Mother. Scholars believe the Odes of Solomon, which include Ode 19, with its feminine attributes of God the Father, relate to the Gospel of John and the Dead Sea Scrolls. The author might have been an Essene convert to the Johannine community.

The Johannine community was distinct from the Jewish Christians, and its writings reflect anti-Jewish sentiments. To Jews, it is blasphemous to say that God is a woman, Jesus is godlike and that they married. To people from the surrounding cultures, such as Greek, Roman and Egyptian, it is not unusual to worship female deities, deify humans and believe that gods mate with humans. To his non-Jewish followers, Christ was godlike, not a human Jewish prophet. Otherwise, they wouldn’t have followed him. What business would they have had with a human Jewish prophet?

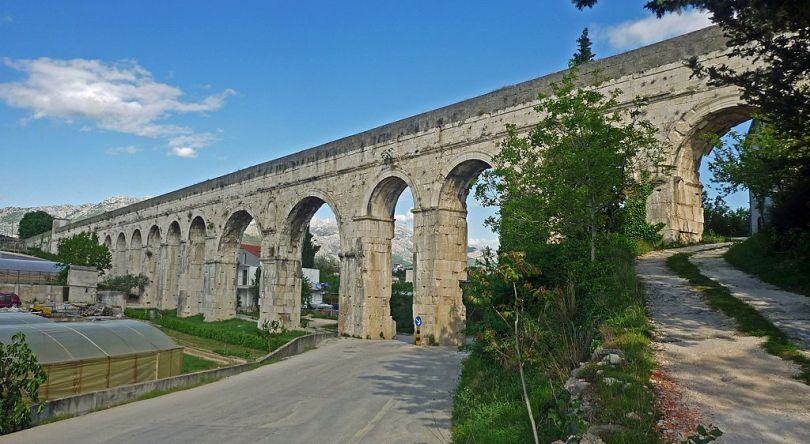

At first, most Christians were Jewish. Their religion would not have permitted them to see God as a woman and Christ as a godlike figure. However, Christianity had non-Jewish converts very early on. Educated Hellenistic Jews were often open to innovation due to their contact with surrounding cultures. Around 42 AD, a group of Christians founded a church in Antioch, located in the Roman province of Syria, which was likely also the location of the Johannine community. The Bible mentions the persecution of Christians and the spreading of their message in Antioch among Jews and Greeks (Acts 11:19).

If the Gospel of John belonged to a separate community that opposed Jewish Christianity, it could be more historically accurate and closer to Christ’s original teachings if that community had fewer reasons to alter the message and historical facts. The motivation for modifying their scriptures was to unify the Church. And so, despite it being the most recent, the Gospel of John could be the best-preserved remnant of original Christianity from before Paul profoundly changed it.

The author of the Gospel of John wrote in good Greek and employed a sophisticated theology with seven signs, and Jesus said seven times, ‘I am.’ Scholars believe he has used several sources, including the Gospel of Mark and Luke, as well as documents that no longer exist. The Gospel of John suggests that one of its sources could have been an eyewitness account.

The Gospel of John implies Jesus’ ministry lasted three years, suggesting more historical detail than the other Gospels. The number three has theological significance, as it is the heavenly number, which makes it suspicious. The author may have rearranged the story accordingly. The close relationship between God and Jesus, and Jesus’ belief in himself as eternal, however, has a historical origin. It agrees with Jesus being Adam, the everlasting husband of God, the Alpha and the Omega. It made him both human and godlike, which was the compromise Paul came up with, and the reason why his theology prevailed.

The Gospel of John has undergone several redactions. If one of the sources has used an eyewitness account or the Johannine community didn’t face the theological restrictions of Judaism, the Gospel of John could reveal more and be more historically accurate than the other Gospels or represent the earliest beliefs more accurately, most notably after identifying and eliminating these redactions. John could thus be the most revealing about the nature of the relationship between God and Christ.

Platonic birth

The Gospel of John provides no information about Jesus’ early life. Instead, it gives a creation myth in abstract wording. Why write an alternative creation story? Does Genesis not suffice? Not if Jesus was Adam, and Adam the Son of Eve, who was God and the Mother of All the Living. The following phrases are noteworthy: ‘In him was life, and that life was the light of all mankind,’ and ‘He gave the right to become children of God -children born not of natural descent, nor human decision or a husband’s will, but born of God.’

Jesus gave us life and the right to become children of God. If he were Adam, he fathered humankind, and because his wife was Eve, we are all children of God if we all descend from Eve and Adam. The Quran says, ‘Truly, the likeness of Jesus, in God’s sight, is as Adam’s likeness, He created him of dust, then said He unto him, ‘Be,’ and he was.” (Quran 3:59) That agrees with Platonism, which was widespread in the Greek-speaking world.

Adam, being the son of Eve, disagrees with the account in the book of Genesis. The scribes who redacted the text that eventually became the Gospel of John devised an obscure formula to mask the issue. It is possible that the initial text provided more details about how precisely Jesus granted us the right to become children of God. Platonic thinking is abstract and about ideas, like us becoming children of God, rather than material facts, like Eve making love to Adam. That was indeed convenient.

And so, under the influence of Platonism, the Word became flesh in the form of Jesus (John 1:14). The phrasing ‘born of God’ suggests that the original author knew God was a Mother. The author affirms this by expounding on that birth. When arguing with Jesus, the Pharisee Nicodemus noted that one cannot enter a second time into one’s mother’s womb to be born again (John 3:4). Nicodemus understood what Jesus meant, which is that Christians are figuratively born of God’s womb and that God is a Mother. Jesus gave it a spiritual meaning in his answer, ‘No one can enter the kingdom of God unless they are born of water and the Spirit.’ (John 3:5)

The wedding

There was a wedding in Galilee (John 2:1-10). Jesus was there, as were his mother and his disciples. When the wine was gone, his mother said to Jesus, ‘There is no more wine.’ That wouldn’t have been his concern unless he was the Bridegroom. Then Jesus answered, ‘Woman, why do you involve me? My hour has not yet come.’ It could mean that Jesus was not the Bridegroom and was about to be married too. He called his birth mother ‘woman,’ perhaps because he considered God his Mother. Jesus started doing miracles at this wedding by turning water into wine. Maybe he became Christ through this wedding. Hence, it may have been his wedding after all, and the scribes may have changed the narrative to make it appear that it was not.

Then John comes up with a statement not found in the other Gospels: “A person can receive only what is given them from heaven. You yourselves can testify that I said: ‘I am not the Messiah but am sent ahead of him.’ The Bride belongs to the Bridegroom. The friend who attends the Bridegroom waits and listens for him and is full of joy when he hears the Bridegroom’s voice. That joy is mine, and it is now complete. He must become greater; I must become less.” (John 3:27-30) Jesus was the Messiah because he was the Bridegroom in a heavenly marriage. The other Gospels also indicate Jesus was the Bridegroom (Matthew 9:15, Mark 2:19 and Luke 5:34).

I and the Father are one

Jesus called God Father, making himself equal with God, so the Jews wanted to persecute him, the Gospel of John says (John 5:16-18). Jesus made other claims in this vein. If the Gospel of John is a redacted insider account, these assertions may reflect Jesus’ words. If Jesus believed himself to be Adam, he could have said, ‘Before Abraham was born, I was.’ And not, ‘Before Abraham was born, I am.’ (John 8:58). The wording ‘I am’ in this phrase implies the godlike nature of Christ and existence before creation. It refers to God saying to Moses, ‘I Am Who I Am [Who Always Has Been And Will Always Be],’ and, “This is what you are to say to the Israelites: ‘I Am has sent me to you.'” (Exodus 3:14) The wording in John implies that Jesus is God, always existing, the alpha and the omega.

Then comes an intriguing assertion, ‘I and the Father are one.’ (John 10:30) Jesus claimed to be a god, so the Jews wanted to stone him for blasphemy (John 10:33). Perhaps Jesus meant something else. Marriage is a way to become one flesh with another person (Genesis 2:24, Matthew 19:4-6). If Jesus had implied he was married to God, it would still have been blasphemy to the Jews. If Mary Magdalene had remained in the background to let Jesus do Her bidding, and Jesus believed himself to be Adam from whom all of humanity descends, Jesus may have said, ‘I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Mother except through me.’ (John 14:6)

Jesus’ claims caused conflict among the Jews. On the one hand, he did miracles, but on the other hand, he offended the Jews by making outrageous claims. The Jews lived under Roman rule. The Romans didn’t care about someone claiming to be God’s husband or any other particularity that offended the Jews. For Pilate, it was difficult to bring a charge against Jesus (John 19:4). The way to convict Jesus was by claiming he was a rebel leader. Claiming to be the Son of God could be a claim to kingship over the Jews. And that was the offence for which the Romans convicted him (John 19:19). The Jewish leaders insisted they had a law. According to that law, Jesus must die because he claimed to be the Son of God (John 19:7). That probably refers to blasphemy rather than claiming to be Israel’s king.

It was a sensitive political environment. Religious extremists and messiah claimants stirred up people who hoped to throw out the Romans and restore Israel’s glory. The Christian tradition depicts the Jewish leaders as evil schemers against Jesus, the Son of God. But John gives us an insight into their motives (John 11:47-50),

‘What are we accomplishing?’ they asked. ‘Here is this man performing many signs. If we let him go on like this, everyone will believe in him, and then the Romans will come and take away both our temple and our nation.’ Then one of them, named Caiaphas, who was high priest that year, spoke up, ‘You know nothing at all! You do not realise that it is better for you that one man die for the people than that the whole nation perish.’

If Jesus were to stir up sentiments and lead a rebellion, the Roman army would come to crush it and destroy the temple and the Jewish nation. It was reasonable to think so, and not particularly evil to try to prevent it. A few decades later, the Jews rebelled, and their dreaded scenario unfolded, so their fears were justified. In any case, such an insightful detail argues for the historical quality of the text.

Love is a central theme, ‘As the Father has loved me, so have I loved you. Now remain in my love. If you keep my commands, you will remain in my love, just as I have kept my Father’s commands and remain in his love. I have told you this so that my joy may be in you and that your joy may be complete. My command is this: Love each other as I have loved you.’ (John 15:9-12) That is an unusual amount of love. If Jesus were God’s husband, you could understand why he said it. That brings us to the loving and intimate relationship between Mary Magdalene and Jesus. The Gospel of John features the anonymous Beloved Disciple. Rumour has it that it was Mary Magdalene.

The Beloved Disciple

The mysterious Beloved Disciple appears only in the Gospel of John. So, why is John so secretive about the identity of this individual? If the editors had removed the marriage between Mary Magdalene and Jesus, they could have changed Mary Magdalene’s role to that of the Beloved Disciple. To become the Beloved Disciple, Mary Magdalene had to take over Simon Peter’s role, who was Jesus’ favourite disciple. To that aim, the scribes have created this disciple from thin air by extracting this person from Simon Peter. This disciple acts like a shadow of Simon Peter throughout the story, except for the scene at the cross.

Had the Beloved Disciple been Mary Magdalene, that would still have generated questions regarding the nature of the relationship between Mary Magdalene and Jesus, or it could have raised women to a position of authority that men weren’t particularly keen on giving them. In a later redaction, the scribes turned the Beloved Disciple into an anonymous figure, distinct from Mary Magdalene, and suggested that he was Jesus’ brother. This perspective proves to be illuminating. Look at the following fragment (John 19:25-27),

Near the cross of Jesus stood his mother, his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene. When Jesus saw his mother there and the disciple he loved standing nearby, he said to her, ‘Woman, here is your son,’ and to the disciple, ‘Here is your mother.’ From that time on, this disciple took her into his home.

If you take the text at face value, the Beloved Disciple was Jesus’ brother, as Jesus’ mother was also his mother. That is a good enough explanation as to why he took her into his home. It could be an intentional edit to make it appear that way, so that it makes sense for the Beloved Disciple to take Jesus’ mother into his home. And if the text were correct, the author of the text can’t be John, because the text claims that the Beloved Disciple wrote it. The fragment also states that four women were near the cross, suggesting that no men were present at the time. And so, the Beloved Disciple could have been one of these four women.

The most likely candidate would be Mary Magdalene. Jesus could have asked Mary Magdalene to take his birth mother into Her home, so that it was something that really happened rather than a figment resulting from the extraction of the Beloved Disciple from Simon Peter. Like John, Mark and Matthew suggest that only women followers were near the cross (Mark 15:40, Matthew 27:55-56). Luke is less specific and states that all who knew him, including the women (Luke 23:48). This contradicts Mark and Matthew, who report that all the disciples had fled (Mark 14:50, Matthew 26:56). John doesn’t mention the fleeing of the male disciples but also doesn’t note their presence.

A few arguments support this view. First, it is odd not to say ‘mother,’ but rather, ‘Woman, here is your son.’ Was someone else Jesus’ mother? Something is off here. Second, it is more likely that Mary Magdalene took Jesus’ birth mother into Her home than a male disciple, unless he was Jesus’ brother. The Gospels mention a group of female disciples travelling with Jesus (Luke 8:1-3). They formed a separate group led by Mary Magdalene, who took care of one another. Third, how could Jesus tell another disciple, ‘Here is your mother.’ After all, it was Jesus’ mother. The only explanation is that this disciple was his brother, while nothing else suggests so. Fourth and finally, by all accounts, Simon Peter was Jesus’ favourite Apostle. Jesus called him the rock on which he would build his Church, and gave them the keys of the kingdom of heaven (Matthew 16:18-19) and appointed him as leader (John 21:15-17). Only Peter had fled the crucifixion scene and wasn’t present.

According to Paul, Simon Peter saw the resurrected Jesus first, and then Jesus appeared to the other disciples (1 Corinthians 15:4-6). The repeated reference ‘according to the scriptures’ suggests that Paul invented the creed. That Jesus appeared to Simon Peter first makes sense as Simon Peter was Jesus’ favourite disciple. The Gospel of John tells a different story. It claims that Mary Magdalene went to the tomb and saw the stone removed from the entrance. She then ran to Simon Peter and the Beloved Disciple and said, ‘They have taken the Lord out of the tomb, and we don’t know where they have put him!’ So Peter and the Beloved Disciple went to the tomb. The Beloved Disciple, acting like a shadow of Simon Peter, came there first but didn’t go in. Then Simon Peter arrived and went into the tomb (John 20:1-6).

He saw the strips of linen lying there. Then the Beloved Disciple also went in and saw and believed (John 20:8). The beloved disciple saw and came to faith, but two men were inside. Remarkably, it is not Simon Peter who saw and believed, even though he was the first to go inside. The Beloved Disciple could be a later addition. If so, Simon Peter was the first to see and come to faith. Perhaps, he saw Jesus there alive. That would confirm Paul’s claim. The Beloved Disciple acts as a shadow of Simon Peter once again. The Gospel of John then tells us that Jesus appeared to Mary Magdalene first (John 20:11-18). It is impossible to have certainty about what occurred, but there was an effort to achieve unity within the Church. The following steps of editing seem plausible:

- God became the Father, but Mary Magdalene and Jesus remained a couple, with evidence of their intimacy. Mary Magdalene told Simon Peter, the disciple Jesus loved, that Jesus had disappeared from the tomb. Simon Peter went in and saw the empty tomb for himself. That may have happened.

- The early Church agreed that Jesus rose on the third day, and that Simon Peter had seen him first. So, Simon Peter went in, saw and believed. Perhaps Simon Peter saw Jesus there alive. Failing a suitable cover story at the time, the scribes truncated the Gospel of Mark.

- The early Church fabricated a cover story for the resurrection on the third day, and removed the marriage. Mary Magdalene became the Beloved Disciple. Jesus appeared to Her first in a newly added section. Simon Peter then saw something, but not Jesus, as Mary Magdalene saw him first.

- Mary Magdalene and the Beloved Disciple became separate individuals. So, Mary Magdalene spoke to Simon Peter and the Beloved Disciple, and both of them went into the tomb. The Beloved Disciple saw something and believed, but Mary Magdalene remained the one who saw Jesus first.

All four gospels hint at Jesus being the bridegroom, so early Jewish and Gentile Christians agreed that Mary Magdalene and Jesus were a couple. If you omit John 20:2-10, John 20:1 together with John 20:11-18 makes a story of its own. That could argue for the insertion of John 20:2-10 into the original text. John 20:11 states that Mary Magdalene was near the tomb, which contradicts the previous lines, and most notably John 20:2. However, the inserted section is John 20:11-31. Mark confirms this.

The original text of Mark finishes with the women going to the empty tomb, where a young man dressed in a white robe tells them that Jesus has risen (Mark 16:1-8). The added section of Mark notes that Jesus appeared first to Mary Magdalene (Mark 16:9). And, according to Paul, Jesus appeared first to Simon Peter. The original story was that Mary Magdalene went to the tomb and found it empty. Jesus’ appearance to Mary Magdalene is a later addition to the text. Matthew says that Jesus appeared to the women first (Matthew 28:10), and Luke tells a different story. Mark and John are the most reliable, so if Matthew and Luke contradict Mark and John, it is most likely that Matthew and Luke are in error.

After this episode, Jesus appeared to the disciples (John 20:19-23). Paul tells the same in 1 Corinthians 15, so if this account is accurate, Mary Magdalene set in motion the resurrection beliefs by inviting Simon Peter to the tomb, and if She was God, She knew what he was about to find there. The problem with this narrative is that it neatly aligns with Paul’s view, expressed in his letter, that Jesus rose on the third day in accordance with the scriptures. To Paul, everything must be according to the scriptures, which makes it iffy, most notably because John has two endings, one in John 20 and another in John 21.

Simon Peter was Jesus’ favourite disciple, and the Beloved Disciple is an extraction of Simon Peter. He enters the story at the Last Supper when he asks Jesus who is about to betray him (John 13:21-25),

After he had said this, Jesus was troubled in spirit and testified, ‘Very truly I tell you, one of you is going to betray me.’ His disciples stared at one another, at a loss to know which of them he meant. One of them, the disciple whom Jesus loved, was reclining next to him. Simon Peter motioned to this disciple and said, ‘Ask him which one he means.’ Leaning back against Jesus, he asked him, ‘Lord, who is it?’

Simon Peter was the one who wanted to know. He was the disciple who asked Jesus who was about to betray him. The Gospel of John has a premature ending in Chapter 20. The premature ending comes from an inserted source. The latter part of John 20, starting at John 20:11, is an insertion, and it probably coincided with the addition of a similar account to Mark, to detail the resurrection on the third day that never happened. The original story was that they found the tomb empty, and that Jesus appeared again to Simon Peter and a few other disciples by the Sea of Galilee after some time had passed. If this is correct, and it likely is, then Jesus appeared only once to Simon Peter and a few other disciples.

And Jesus’ appearance explained the empty tomb. The logical conclusion, for Jews at least, from an empty tomb and Jesus appearing again after his death, was resurrection. Something like that happened. Otherwise, there would be no Christianity. One can still question what they saw or whether they lied, but few would believe such a miracle if Jesus hadn’t performed miracles before. That it happened on the third day is an invention for theological reasons, undoubtedly conjured up by Paul, so that it would be ‘according to the scriptures,’ which was his personal obsession.

That also explains why Mark’s ending was premature. The historical facts contradicted the agreed-upon ones, and there was no cover story yet at the time the author of Mark held his pen to write his Gospel, as there was none for the virgin birth. That came later. The initial plan was to replace John 21 with the latter part of John 20, but someone bright concluded it was a waste of a good text, and added it again at the end, which explains the premature ending in John 20. An abstract of this revised account, thus John 20, became the added conclusion of Mark.

The final chapter of the Gospel of John mentions a rumour amongst believers that the Beloved Disciple would not die. Jesus believed some of his disciples would live to see his return (Mark 8:34-38, 9:1). In John, Jesus said, ‘Very truly I tell you, whoever obeys my word will never see death.’ Still, the wording is remarkable (John 21:20-23),

Peter turned and saw that the disciple whom Jesus loved was following them. (This was the one who had leaned back against Jesus at the Supper and had said, ‘Lord, who is going to betray you?’) When Peter saw him, he asked, ‘Lord, what about him?’ Jesus answered, ‘If I want him to remain alive until I return, what is that to you? You must follow me.’ Because of this, the rumour spread among the believers that this disciple would not die. But Jesus did not say that he would not die; he only said, ‘If I want him to remain alive until I return, what is that to you?

The text suggests the rumour was that the Beloved Disciple would not die at all, not merely until Jesus returned. Otherwise, the text would not note it so explicitly. Why might this disciple not die at all? Why only the Beloved Disciple? And why mention the rumour and try to dispel it? And then repeat the explanation twice, as if that required stressing? It seemed something of the utmost importance. And it is part of the original text, so it has a historical origin.

The rumour becomes understandable if Mary Magdalene was God and had become the Beloved Disciple in an earlier redaction. Simon Peter probably discussed Mary Magdalene’s immortality with Jesus. After all, he was Jesus’ favourite disciple. Here again, the Beloved Disciple appears as a shadow of Simon Peter (John 21:20), as he did at the Supper and the entrance to the tomb. The Beloved Disciple allegedly wrote down his testimony (John 21:24), making Simon Peter the most likely source of the eyewitness account. The author of Mark probably used that same eyewitness account.

The validity of the Gospel

The deification of Jesus was an early tradition. If you are God’s husband who lives eternally, you are already godlike, even if you are human. In other words, the Gospel of John might be more historically accurate than the others. Mark can be a good addition. The start of Mark makes it possible to conclude that Jesus started as a disciple of John the Baptist, which is something you can’t infer from John. Turning Mary Magdalene into the Beloved Disciple may have coincided with the insertion of the latter part of John 20, which was contrived to detail the resurrection occurring after three days. It is the reason why the latter part of Mark has gone missing. It contradicted the resurrection-after-three-days narrative. After eliminating the redactions, the Gospel of John may be the most accurate narrative of what has transpired.

Historians and biblical scholars doubt the resurrection and the miracles Jesus performed. These miracles contradict the laws of nature, so it is reasonable to think that these miracles never occurred. However, in virtual reality, miracles can happen, which casts doubts on that argument. If the Gospel of John is a redacted insider account, it may be more accurate or more revealing than most biblical scholars and historians currently assume. John also circulated in a Gentile tradition outside Jewish and Pauline Christianity that had fewer problems with the facts. And so, John could be more precise or more telling than the other Gospels, as they aren’t insider accounts and come from a tradition hostile to the idea of God being a woman who married Jesus.

Jesus appeared to some of his disciples shortly after the crucifixion. You can’t imagine Christianity beginning without Jesus appearing to some of his followers. That his followers had seen Jesus after he supposedly had died strengthened their beliefs that Jesus was Adam, who lived eternally and was the Son of God. The resurrection of the dead was a belief amongst some Jews at the time, and it seemed the best explanation for what they saw, thus the body disappearing and Jesus appearing, so they labelled the event like so.

Remarkably absent in John is the story of Jesus’ transfiguration. It is present in Mark, Matthew and Luke. If John is more accurate, the transfiguration could be a myth. To Christians, the transfiguration is evidence of Jesus’ divinity. The reason for inventing the transfiguration story may have been to fulfil an earlier prediction by the prophet Malachi.

John also doesn’t mention breaking the bread and sharing the wine during the Last Supper, and it may be more than just an omission. The body and blood of Christ, representing the new covenant, are part of the sacrificial lamb imagery that Paul introduced. Jesus never said, ‘Take it; this is my body,’ nor, ‘This is my blood of the covenant, which is poured out for many.’ The Torah requires firstborns of the flock and herd to be brought as sacrifices (Deuteronomy 12:6, 15:19), and Jesus was God’s firstborn.

The Jewish tradition sees human sacrifice as a grave sin. The Jewish Bible condemns child sacrifice as a barbaric custom (Leviticus 18:21, 24-25; Deuteronomy 18:10), so the reasoning is most peculiar indeed. John is the most outside the Jewish tradition. If it had happened, John more likely would have mentioned it, and the other Gospels more likely would have left it out in order not to offend the Jewish audience.

It also presents a possible explanation for the seven demons Jesus supposedly cast out of Mary Magdalene. Mark mentions it in the later-added section at the end (Mark 16:9), suggesting it was not an original belief. You can also find it in Luke (Luke 8:2). Had a separate Gentile Christian tradition claimed that Mary Magdalene was God, mainstream Pauline scribes might have introduced this peculiarity to stress that She was not.

It is impossible to uncover all the redactions. It appears that there have been at least four rounds of modifications to the text. The final version dates back to approximately 95 AD, reflecting the perspective of that era. After the Romans had destroyed the Jewish temple in 70 AD, Christians realised that Jesus might not return anytime soon. The character of the faith changed accordingly, from expecting Jesus’ return with power and glory to having a personal bond with Jesus that gives access to eternal life. The Gospel of John reflects this change in outlook.

Figuratively speaking

In the Gospel of John, Jesus doesn’t always speak in clear and precise terms. He says, ‘I have much more to say to you, more than you can now bear. But when he, the Spirit of truth, comes, he will guide you into all the truth. He will not speak on his own; he will speak only what he hears, and he will tell you what is yet to come. He will glorify me because it is from me that he will receive what he will make known to you.’ (John 16:12-14) Muslims see these words as a prediction of the coming of Muhammad. That is unconvincing.

Chapter 16 of the Gospel of John excels in vagueness. It contains a remark that appears insignificant among the obscurity but might be there for a reason, saying, ‘Though I have been speaking figuratively, a time is coming when I will no longer use this kind of language but will tell you plainly about my Father.’ (John 16:25) Why should Jesus not speak plainly about God? The scribes who modified this gospel may have known what they were doing and realised the truth would come out one day. And that day may finally have arrived.

Latest revision: 8 November 2025

1. How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher. Bart D. Ehrman (2014). HarperCollins Publishers.