What is knowledge theory?

What is truth, and what is knowledge? Philosophers have been discussing these questions for thousands of years. It is the domain of knowledge theory, also called epistemology. It deals with truth, belief, and the justification of beliefs. It aims to answer questions such as: What do we know? What does it mean that we know something? And what makes beliefs justified? We usually acquire knowledge in two ways:

- by induction, which is using observations to formulate general rules or theories, and

- by deduction, which is applying those rules and theories to specific situations.

How does that work? Let’s give an example. After carefully investigating the records of people who have lived and still live, you conclude, with the help of induction, that people typically die before they reach 120. Using this rule and deduction, you infer you will die before the age of 120. That seems straightforward, but there are pitfalls, so philosophers continue to discuss these issues.

There is a difference between rules and theories. A rule is that if A occurs, B happens. A theory is that A causes B. If we can’t observe A, the theory assumes its existence. A then exists in our imagination. The explanation of electricity assumes the existence of electrons and their behaviour. We can’t see electrons, not even with a powerful microscope. We can do experiments to see how electricity behaves. We presume the conduct of electricity proves the existence of electrons, so experiments demonstrate their existence. It is like living in the dark and assuming that cows exist, even though we have never seen them. We have theorised that such animals say moo, so our hearing of moos proves the existence of cows. So if we hear moo, that must be a cow.

We are imaginative beings. Our knowledge involves imagination. We imagine electrons and gravity. Dogs can’t imagine electrons or gravity, so they can’t build electric cars or aeroplanes. Electrons and gravity may exist in our imagination, but they point at something real. Otherwise, objects wouldn’t fall to the ground, and we wouldn’t drive electric cars. This discussion of knowledge theory is a historical account. New ideas usually build upon previous thoughts. This treatise discusses Western philosophy. Western thinkers have been the most inquiring. As a result, the Scientific Revolution began in Europe. Science is the result of thinking, but it has also greatly influenced thought. It started with the ancient Greeks. What distinguished them from other traditions was their rational thinking.

Classical philosophy

Some 2500 years ago, Greek philosophers speculated about the nature of reality. Some claimed everything consisted of fire, water, earth and air. Later, a few philosophers argued that the building blocks of reality are small particles called atoms. These atoms differ in size and shape for different materials. The objects we see are groups of atoms stuck together. Democritus argued that the universe merely consisted of atoms in the void. That is already close to what we believe today. Speculation about the nature of reality, such as whether matter consists of atoms, is metaphysics.

Metaphysics is about how we perceive reality. We connect the dots in a particular way. It is our imagination. We can believe that everything consists of fire, water, earth and air, or we can think that atoms are the building blocks of everything around us. It was speculation because these atoms were invisible, and the Greeks had no microscopes to verify their existence. By assuming atoms exist and have different shapes and sizes, you can explain the presence of various substances. You can also do that by presuming everything consists of fire, water, earth and air. Only we find atoms more convincing.

The ancient Greeks also pondered other issues. Some figured that the Earth is a sphere. When you look at the sea, you see the horizon slightly curved, and boats disappear in the distance before their sails do. A philosopher named Xenophanes doubted religion. He realised that people believed that the gods were like themselves. Black people believed the gods were black, while red-haired people thought they were red-haired. Xenophanes claimed it was impossible to know the gods and how they looked. It was an early form of scepticism.

And why should you worship the Greek gods if the Persians and the Egyptians bow before other gods? If your birthplace determines your beliefs, your beliefs are likely false. The sophists were philosophers who had come into contact with different cultures. They claimed that absolute knowledge is impossible. Everything is subjective, they argued. This view is called relativism. Socrates is known for his dialogues in which he debated the sophists.

According to Socrates, there is absolute truth, even though we don’t know that truth. His pupil Plato later claimed that ideas are the basis of knowledge and that ideas, not objects, are the building blocks of reality. His view is called idealism. It relates to deduction. Plato’s pupil Aristotle asserted that knowledge comes from observation. His approach is called empiricism. It works like induction. Both methods come with problems. If you imagine a unicorn, you have the idea of a unicorn, and the idealist could claim unicorns exist. On the other hand, if you see a unicorn after eating some mushrooms, the empiricist could also say unicorns exist.

And so, knowledge can always be called into question. If no one has ever seen a unicorn, this isn’t definite proof of their non-existence. These creatures could still be hiding deep down in the forests. And perhaps eating mushrooms enhances your senses, allowing you to see things that would otherwise remain hidden. It is for that reason that scepticism emerged. There were two groups of sceptics. The first claimed that nothing is certain. They aimed to refute the claims of other philosophers. The second argued it is better to postpone judgment until the matter is sufficiently clarified.

These ideas revived in Europe in the late Middle Ages after classical philosophers’ texts turned up in Arab libraries. European philosophers like Thomas Aquinas and William of Ockham were also theologians. They believed that there was no difference between theology and science. Over time, science and religion went their separate ways. Their paths separated. Today, science requires empirical evidence, while religion doesn’t. Scientists test assumptions, such as the existence of electrons, with experiments that others can verify. In religion, evidence is often personal, such as most appearances of the Virgin Mary, and experiments like checking the answers to prayers never yield anything substantial.

The most obvious explanation is usually correct, or what occurs most often is most likely the case. If you see something flying in the sky, it probably isn’t Superman. And so, it is rational first to ask yourself, ‘Is it a bird? Is it a plane?’ Once you have ruled out these possibilities, you can conclude, ‘No, it is Superman!’ William of Ockham is known for his simplicity principle, Ockham’s Razor. It says the explanation with the fewest required assumptions is preferable. If what you prayed for transpires, you could check whether it might be a coincidence before claiming it is God answering your prayer. The latter requires God’s existence, and that this supposed infinitely powerful being, which rules billions of galaxies, listens to your particular request while ignoring many others. In contrast, coincidence doesn’t require those assumptions.

Modern philosophy

In 1492, Christopher Columbus sailed to America. Ancient sources, including the Bible, didn’t mention this enormous, lurking continent stretching from the North Pole to the South Pole. A little later, Nicolaus Copernicus claimed that the Earth revolved around the Sun rather than the other way around, which everyone believed until then. Traditional knowledge had failed dramatically. Copernicus had the luck of dying soon. The Catholic Church prosecuted Galileo Galilei for claiming Copernicus was right and the Bible was wrong.

At the same time, Protestants challenged the authority of the Catholic Church by making religion a personal matter. If you had reason to believe something, it could be correct. Religion is about your conscience rather than what the Church teaches. The number of issues on which we can disagree is infinite, so we have 45,000 branches of Christianity today. The ensuing religious wars ravaged Europe and ended without a clear winner.

And who was right? There can be only one truth. Merely believing something doesn’t make it true. However, questioning the existence of God was initially out of the question. European philosophers sought a rational foundation for religion, attempting to base it on verifiable claims, an effort known as deism. The project failed because it was impossible to establish the properties of the invisible fellow in the sky that everyone imagined.

The confusion spurred renewed scepticism and a new search for the foundations of knowledge. As philosophers from continental Europe, such as René Descartes, Gottfried Leibniz, and Baruch Spinoza, argued, our senses are deceptive. Therefore, only rational thinking can generate knowledge. This school is called rationalism, but it was a refurbished idealism.

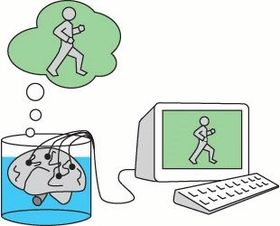

In a thought experiment similar to the brain-in-a-vat scenario, Descartes questioned everything the senses register. Your brain could be inside a vat filled with a life-supporting liquid and connected to a computer that generates the impression you are walking. What is beyond doubt, according to Descartes, is that you exist, even when you are just a brain-in-a-vat. And you can establish this fact by thinking. ‘I think therefore I exist,’ he concluded.

Other philosophers from Great Britain, such as Francis Bacon, Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and David Hume, argued that knowledge comes from observations. It was a renewed empiricism. A philosophical divide emerged between idealist continental Europe, most notably Germany and France, and empiricist Great Britain, as well as later the United States. The duck test is an example of pragmatist empiricism. It says that when something looks, quacks, and walks like a duck, it probably is a duck. It is not a coincidence that a US writer rather than a German philosopher invented it.

The divide affected moral philosophy and views about society. The empiricist view holds that ethical rules are whatever people agree on, thus reflecting society’s sentiments. The idealist vision is that morals are absolute and apply to everyone. Idealistic schemes to improve society, with religious claims to being the truth, such as Marxism, came from continental Europe. Pragmatic thinkers, including Adam Smith, the intellectual father of Capitalism, came from Great Britain or the United States. Smith attempted to describe what had happened and offer practical guidance on how to manage an economy.

It was an era marked by advances in the natural sciences. These advances were the result of thought. And the advances, in their turn, spurred thinking. It was the combination of observation and thought that led to scientific progress. You can investigate the effect of gravity on the motion of objects. You can do so by dropping an iron ball from a tower. You can release the ball from different heights and measure how long it takes for the ball to hit the ground. The table below contains the results of these measurements.

| Height (in metres) | Time (in seconds) |

| 0.05 | 0.10 |

| 0.50 | 0.32 |

| 1.00 | 0.45 |

| 5.00 | 1.01 |

| 10.0 | 1.43 |

| 50.0 | 3.19 |

It requires considerable thought to get the formula representing the relationship between height and fall time: fall time = 9.81 * √ (2 * height). For instance, 3.19 = 9.81 * √ (2 * 50.0). If the tower is only 50 metres high, you cannot measure how long it will take for the ball to fall from 100 metres. With the help of the formula, you can calculate the fall time without the need for measuring it: 9.81 * √ (2 * 100) = 4.52 seconds. It is the combination of observation and thinking that made this possible.

Finding the mathematical formula that matches the data is like solving a jigsaw puzzle. This method of reasoning is induction. It is establishing a general rule based on observations. You can never be sure the outcome is correct. Using your sightings and induction, you might conclude that all swans are white. And if you go to the Moon to drop an iron ball from a tower over there, you will discover that the relationship between height and fall time is different from Earth.

Another way of reasoning is deduction. It involves working from assumptions to conclusions using logical reasoning. If the premises are all justified and the rules of logic are correctly applied, then the inference must be correct. Thus, deduction is applying general rules to specific situations. If all humans are mortal (first premise), and Socrates is a human (second premise), then Socrates is mortal (conclusion). Also, if the relationship between height and fall time is fall time = 9.81 * √ (2 * height) (first premise), and the tower is 100 metres (second premise), then the fall time is 4.52 seconds (conclusion).

The scientific method combines thinking, induction and deduction. Simply put, a scientist uses observations and thinking to produce a theory. You need observations to find the formula representing the relationship between height and fall time. The observations alone are not enough. It requires some puzzling to find the formula. Once you have found the formula, you can use deduction and experiments to check its validity. You can calculate how long it will take for a ball to fall to the ground from 321 metres. You can go to the top of the Eiffel Tower to drop the ball and measure how long it takes before it hits the ground. If the measurement equals the calculated time, the theory works.

Kant and Hegel

The German philosopher Immanuel Kant didn’t settle for a duck test. Germans get to the bottom of things. He aimed to uncover the foundations of our knowledge. Kant realised knowledge arises from observation (empiricism), but we can’t know anything without thinking (idealism). We interpret observations. We recognise differences, count instances and think of cause and effect. Our thinking imposes its structure upon our observations. It is our nature. If we see a tree, we see branches and leaves. We see that the leaves are green and that the branches are brown. We see a difference between a tree and a deer. We can count trees. The concept of a tree encompasses other ideas, such as branches, leaves, greenness, and brownness.

We view the world through our framework, which is language. Without the word tree, we don’t see trees. So, if we only have the words animal and plant, a tree is a plant to us, and we don’t see a difference between trees, bushes, grass, and ferns. We don’t know reality or the things in themselves (relativism). We attach the categories to our perceptions. Speculation about the nature of reality, such as asking whether trees, gravity, or electrons exist, is pointless. Kant is also famous for attempting to find a rational foundation for absolute moral rules.

Subsequent idealist philosophers disagreed. They believed the mind creates reality, so absolute knowledge is possible. They argued that reality is subject to our perception, allowing us to uncover it. The fall of a ball is subject to mathematical laws invented by the human mind. You can claim gravity causes the ball to fall, even though gravity exists only in our imagination. Imagining gravity enables us to predict how long it takes for a ball to reach the ground after being dropped from a tower. Our predictions coming true corroborate that Sir Isaac Newton’s imaginary invisible friend, gravity, indeed exists. You can poke fun at gravity this way, but gravity has proven to be a trustworthy companion, more dependable than many people you can see and touch.

The most notable idealist philosopher was Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel. He argued that we increase our knowledge over time, so there is progress. If we dig deeper, we may learn more about trees, for example, where their roots are. The more we know, the closer we come to the absolute truth. However, by decomposing reality into parts and analysing them, we lose the essence of the whole. We are part of reality and interact with it. Hence, we are one with everything around us and history. We can comprehend reality only in this way. And in doing so, we might find the ultimate answer, which is why we exist. Hegel was also a religious man, so he expected us to discover God at the end of our quest for knowledge.

Seeking knowledge is a process that never stops. You can ask yourself, ‘Is the way I look at the subject correct and adequate? Have I not forgotten something?’ After we arrive at a conclusion, our experiences and thoughts continue, or the situation changes, and we may come to a different belief later. Hegel called it dialectic. Our knowledge increases. It pushes forward, leading to progress. Hegel’s dialectic has three phases:

- an initial thought or assertion (thesis),

- a contradicting or supplementing argument (antithesis, negation),

- and the integration of the two into an improved insight (synthesis).

Contemporary philosophy

Kant ended the idea that metaphysics gives us knowledge. Philosophers became less ambitious from then on. One reaction was pragmatism. The theory of evolution may suggest that we hold beliefs to survive and reproduce. Pragmatic American thinkers, such as Charles Sanders Peirce and William James, viewed thinking as a means of solving problems. They were not interested in truth or the nature of reality. Another approach, hermeneutics, with German thinkers like Wilhelm Dilthey and Martin Heidegger, concerns human communication. Dilthey argued that natural sciences are about interpreting observations while the humanities are about meaning and, in the case of Heidegger, what it means to exist.

Others embarked upon a renewed search for the foundations of knowledge. Analytical philosophers such as Bertrand Russell and Ludwig Wittgenstein believed that the primary tools of philosophers were language and logic. They aimed to develop a new method to gather knowledge. There is an outside world, and language expresses facts about that reality, or so they argued. This view is known as realism, which is closely related to empiricism. They claimed there are justified true beliefs. Jane might think something is true based on what she knows. If this is indeed the case, her belief is justified.

Karl Popper introduced the idea of falsification. You can never prove a hypothesis is correct, but you can prove it is wrong when you find contradicting evidence. That is also scientific progress because knowledge increases. The theory you believed in is incorrect. You might think all swans are white as long as you only see white swans. Once you spot a black swan, your theory is proven wrong. From then on, you think most swans are white while some are black. It is the way knowledge progresses. The belief that most swans are white and some are black is closer to the truth than the idea that all swans are white, even if a red swan is lurking somewhere out there that no one has ever seen.

Scientific theories must be falsifiable. Otherwise, they aren’t scientific. Scientific theories must enable us to make predictions that we can test. As long as these predictions come true, we assume the theory is correct. We can’t be certain, but the theory works for us. You can go out and look for swans and check their colour. Your theory says they must be either black or white. You can use the mathematical formula reflecting the relationship between height and fall time to calculate the fall time from 100 metres. If you do an experiment and the outcome differs from the calculation with the formula, the theory is wrong unless your measurement or computation is in error.

As our knowledge increases, our understanding of reality changes. Philosophers call that a paradigm. It also happens in science. Thomas Kuhn noted that scientific paradigms change over time. A scientific paradigm is a theory or system of ideas that dominates a field, such as physics. Existing theories don’t explain everything. The theories that clarify the most phenomena and leave the fewest unexplained are the best and form the paradigm in the field. The paradigm of your knowledge of swans is that swans can be black or white. It is better than your previous belief that they are all white. When you discovered a black swan, your paradigm shifted. You changed your opinion.

Edmund Gettier criticised the notion of justified true beliefs. You can be correct for the wrong reasons. Suppose Jane looks at her watch. It says it is two o’clock. She believes it. She doesn’t know it stopped exactly twelve hours earlier. Her belief is thus not justified. The watch accidentally gives the correct time, so her belief is true nonetheless.

As our knowledge increases, our understanding of reality changes. Philosophers call that a paradigm. Thomas Kuhn noted that scientific paradigms change over time. A scientific paradigm is a theory or system of ideas that dominates a field, such as physics. Existing theories don’t explain everything. The theories that clarify the most phenomena and leave the fewest unexplained are the best and form the paradigm in the field. The paradigm of your knowledge of swans is that swans can be black or white. It is better than your previous belief that they are all white. When you discovered a black swan, your paradigm shifted. You changed your opinion.

Unexplained phenomena, such as unexpected readings on instruments, might indicate that the paradigm is incorrect. As long as there is no better explanation, most scientists attribute them to errors. At some point, the evidence accumulates that the theory is erroneous. Then, a scientist comes up with a better hypothesis, and out of the confusion, a new paradigm arises. Newton’s laws have long been the paradigm in physics. However, when scientists developed more precise instruments in the 19th century, they gave readings that Newton’s laws couldn’t explain. Initially, most scientists disregarded the evidence. It took a while before a fellow named Einstein could explain them. From then on, Einstein’s theories became part of the new scientific paradigm, quantum physics.

Paradigms in science affect how we see the world. Five centuries ago, most people in Europe believed the Earth was flat, a few thousand years old, and at the centre of the universe. Only a few educated people were aware that the ancient Greeks had discovered evidence of the Earth being a sphere. Despite the efforts of flat-earthers and creationists, most people today believe the Earth is a sphere, billions of years old, and an insignificant dot in the universe.

Paradigms in science profoundly affect how we see the world. Five centuries ago, most people in Europe believed the Earth was flat, a few thousand years old, and at the centre of the universe. Only a few educated people were aware that the ancient Greeks had discovered evidence of the Earth being a sphere. Despite the efforts of flat-earthers and creationists, most people today believe the Earth is a sphere, billions of years old, and an insignificant dot in the universe.

Existing religions and ideologies, or the so-called Big Stories, are all wrong. It gave rise to post-modernism. Post-modernists claim that great stories like religions and ideologies are dead, and absolute knowledge is impossible. Words like ‘reality’ and ‘truth’ are totalitarian concepts, they argue. There is only room for small stories, lived experiences, and perspectives. A great source of inspiration was Friedrich Nietzsche. He proclaimed the death of God and heralded the end of the Christian story of God’s people on the road to Paradise, which gives meaning to our existence. And suddenly, we were out there, without God, condemned to give meaning to our petty existences ourselves. Post-modernism is not much more than relativism with a new marketing campaign. This view was, not surprisingly, criticised by those who claimed the truth is out there somewhere.

So, we are more or less back to where Socrates refuted the sophists. The truth is out there. Believing something doesn’t make it the truth. And if there is a truth, we might be able to find it. With the simulation hypothesis, speculation about the nature of reality or metaphysics re-emerged. We could all live as mindless figures in a computer simulation of an advanced post-human civilisation. It seems that knowledge theory remains stuck. At least, it is clear that while our knowledge has grown dramatically over the last 2,500 years, knowledge theory has not progressed accordingly.

Data, information, knowledge and wisdom

There is a difference between data, information, knowledge and wisdom. Data refers to signals or symbols, like letters or numbers. Data doesn’t need to have meaning. A noise you hear is data. The sequence Q&7nn?9Y is also data. Information refers to what data means. You have information if you know the noise you hear comes from a car engine. There is a car with its engine running nearby. Characters together can form words and sentences that can have meaning if you know the context. So, if you read sales were up 25% last month, this can be information, but only if you know the corporation it applies to.

To acquire knowledge, you need information, and it must be accurate. You may read that sales are up by 25%, but it doesn’t have to be true. And the noise you hear might come from a television. Wisdom refers to understanding. Knowledge itself doesn’t necessarily lead to better insights and decisions. It can be hard to discern between the important and the insignificant. Conflicting information can make you indecisive. Or you ignore crucial information to act more decisively.

The amount of data used and stored is growing fast. Most data is not information but entertainment, such as cat videos on YouTube. A small portion may include information such as sales data. Whether data is considered information depends on your objective. If you look for the meaning of life, you don’t need sales data. For any investigation, only a fragment of the available data is relevant. It requires wisdom to understand which data is helpful and what it means for the inquiry. The amount of data increases faster than the amount of information. The amount of information increases faster than our knowledge. And wisdom can’t be measured, but likely, it doesn’t increase at all.

Proof and evidence

There is a difference between proof and evidence, even though we use these words interchangeably. The definition of proof is a final verdict that removes all doubt, whereas evidence supports a particular explanation. Proving is typically done through deduction, while induction involves using evidence. Proof requires the premises to be correct, which is problematic because the premises used in deductive reasoning, such as the relationship between height and fall time, are often attained by induction. In mathematics, proving is possible. It is pure deductive reasoning without applying it to reality. So, 1 + 1 = 2 is always true. However, if you think you see two trees, someone else may disagree. Perhaps the other person sees three trees or only bushes.

We don’t know everything. With a limited sample of swans and induction, you could conclude that all swans are white. We support claims with evidence, such as experiments, but we can never be certain that relationships like those between height and fall time are always the same. There is no proof, not even in science, but scientific evidence meets the quality standards of the scientific method. They involve careful observation and rigorous criticism, as we can be wrong about what we observe or think. A scientist may use observations to formulate a theory about the fall time of objects and then check it with experiments.

Words like ‘establish’ and ‘conclude’ bridge the gap between proof and evidence. Science aims for the best explanation for the observations. A hypothesis needs evidence and must explain the observations better than the alternatives. Assuming this universe is a simulation, we can explain phenomena that are currently unexplained, such as paranormal events. Rigorous scepticism could be filtering out paranormal events that don’t have multiple credible witnesses or other plausible explanations. However, we can’t test the hypothesis with experiments, so the simulation hypothesis is not scientific.

Scientific proof means that all the experiments confirm the theory. The problem with that is the same as with the swans. If you believe all swans are white, it is scientifically proven until you run into a black swan. That is why all our present knowledge about our existence, the age of the universe, and the laws of nature suddenly becomes void if we discover that we live inside a simulation. The simulation hypothesis can explain the unexplained and is closer to the truth, much like the theory that most swans are white, with some being black. Even so, there could still be a red swan out there that we don’t know about.

Takeaways

Science can’t prove this universe is a virtual reality, but the evidence could be strong enough to establish that we do. It is, however, metaphysical speculation, not much different from saying that Sir Isaac Newton’s imaginary invisible friend, gravity, causes a ball to fall to the ground. The only difference is that gravity is predictable, so you can do experiments and check this friend’s existence. The computer we exist in could be less imaginary than Newton’s friend. You can only make that argument if you understand what knowledge is. So, here are some considerations:

- We can always question assertions because the methods to arrive at knowledge, induction and deduction, can lead to wrong conclusions.

- The validity of a statement depends on its accurately describing (some part of) reality. You can verify it with observations and induction. If things occur that violate the statement, it must be wrong.

- The truth or falsity of a system of statements depends on its logical consistency. You can check a system of statements using logic and deduction. Contradictions point to errors.

- A claim is plausible when sufficient evidence supports it, while no credible evidence contradicts it. Contradicting evidence nullifies it. In science, that is the falsification principle.

- For survival, usefulness is more important than the truth. Religions help us cooperate, and that allows us to survive, which is their primary function.

- Exotic explanations, such as a flying object being Superman, make sense only if common explanations don’t. When dealing with unexplained phenomena, you may have to consider them.

- Minimalism argues for using as few assumptions as possible to establish a point. Assumptions are always questionable. It prompts us not to engage in unnecessary speculation or to use irrelevant data. That is why this booklet is thin.

- Contradicting arguments can be correct in their own right, as there could be a higher truth or synthesis. Evolution and creation can both be correct if we live in a simulation. The simulation hypothesis resolves the question.

- Proof means the absence of doubt, which is impossible in dealing with reality. Evidence can still support a particular explanation or theory. You can still look for the best explanation for the observations.

Latest revision: 12 August 2025

Featured image: Owl eyes. Brocken Inaglory (2006). Public domain.

Other images: Brain-in-a-vat. Alexander Wivel (2008). Public domain.