Setup

Natural Money is an interest-free demurrage currency. It features a holding fee on currency and a maximum interest rate of zero on money and loans. The Natural Money currency is an accounting unit only, as the holding fee, which may range from 0.5% to 1% per month, makes the currency unattractive to hold. Therefore, the currency will not circulate, nor will someone invest in it. Cash, bank deposits, bonds, stocks, real estate, and other investments aren’t currency and therefore not subject to the holding fee. Not paying the holding fee and the curtailment of credit, and thereby inflation, caused by the maximum interest rate, can make lending at negative interest rates attractive.

Natural Money features a separation between regular banking, also known as commercial banking, which involves lending and borrowing, and investment banking, also referred to as participation banking, which involves participating in businesses. Regular banks guarantee returns to their depositors and use their capital to cover losses. Participating banks have shareholders who share in the profits and the losses. These two bank types should remain separated, even though one bank might offer both in distinct accounts. A commercial bank’s funds should be used only for lending. The maximum interest rate limits lending, allowing equity to replace debt in the financial system.

Evidence from history

There is little historical data on the subject of interest-free demurrage currency. Financial systems founded on interest-free money with a holding fee have never existed. There were holding fees and interest bans, but the combination of both has never existed. More importantly, a usury-free financial system requires a high-trust society founded on moral values where investments are safe, and is only feasible with the help of several relatively modern financial innovations. That all seems too good to be true, but we can have dreams. And so, the evidence from history is of limited value.

Several ancient societies have seen usury-induced economic crises. Extreme wealth inequality, often accelerated by usurious lending, regularly coincided with societal collapses. It is a recurring pattern that has existed since time immemorial. The Sumerians were already familiar with charging interest and its disastrous social consequences. Sumerian rulers began implementing debt jubilees as early as 2,400 BC, cancelling debts and freeing debt slaves. Other cultures, such as those in Israel, have banned charging interest. Israel also had debt jubilees every fifty years.

The Egyptian grain-backed currency existed for over 1,000 years, suggesting it provided monetary stability. Nevertheless, ancient Egypt has seen economic crises, often due to droughts causing crop failures, high taxation during warfare, or a weakening central government. The government mitigated famines with its grain reserves, but prolonged famines depleted these facilities, leading to civil unrest and, sometimes, a collapse of order. There is no evidence of social benefits of this money for Egyptian society. Charging interest was common, and Egypt had debt cancellations.

In the Middle Ages, the Church forbade charging interest. Christians, like Jews, were each other’s brothers and couldn’t charge each other interest. When economic life became more developed, the ban on interest became difficult to enforce. In the 14th century, partnerships emerged where creditors received a share of the profits from a business venture. As long as the share remained profit-dependent, it was not illegal, as it was a participation in a business rather than lending at interest.1 Islamic finance works with similar principles.2

In the 17th and 18th centuries, interest ceilings replaced bans. To circumvent the interest ceilings, a creditor and debtor could secretly agree on a fraud, whereby the creditor handed over less money than stated in the loan contract, so that the borrower actually paid more interest.3 More recent experiences with Regulation Q in the United States, which imposed maximum interest rates on bank accounts, suggest that a maximum interest rate is enforceable only if it does not significantly impact the bulk of borrowing and lending.4

An effective ban on usury requires a society grounded in moral values rather than profit. It requires us to live modestly and within the planet’s limits. It also requires societies to care for vulnerable individuals, so that they don’t fall prey to usurers. You shouldn’t charge interest, not merely because it is illegal, but because it contributes to something profoundly evil. That points to a broader problem. We should care about the world and consider the consequences of our actions. Even when what we do is legal, it doesn’t mean that it is good.

Implementation

To implement Natural Money, interest rates must already be low or negative. Attempting to lower interest rates when market conditions don’t justify that move would likely scare investors. Low interest rates require trust, which requires financial discipline, including fiscal discipline from governments. That doesn’t equal austerity, since governments earn interest on their debts when interest rates are negative. The transition preferably is a gradual process that the authorities communicate in advance. Whether that is possible at all remains to be seen, as the implementation may occur in exceptional times.

If there is still a functional currency, the first step is for the government to balance the budget. The second step is to decouple cash currency from the administrative or central bank currency. The move encompasses retiring central bank-issued banknotes and replacing them with treasury-issued banknotes. Not everyone will hurry to a local bank office to exchange banknotes, so the central bank-issued banknotes must be exchangeable at par for the new banknotes for a considerable period.

As long as interest rates are significantly above zero, a holding fee won’t bring them down. Setting a maximum interest rate can lower interest rates by curtailing credit, thereby cooling the economy. To avoid disrupting financial markets, the implementation must be gradual. The maximum interest rate should be high enough to avoid disrupting the economy. Initially, authorities could set the holding fee at a low percentage, or not at all. As interest rates fall, authorities can lower them.

The zero lower bound is a minimum interest rate. It operates like a price control by preventing interest rates from moving freely to the rate where supply and demand for money and capital balance. That is to the advantage of the wealthy, as they can take the economy hostage by demanding a minimum return on their investments. When returns are low, investors may prefer cash over investments, which can hinder an economic recovery. Economists call it liquidity preference.

Low interest rates can prompt lenders to seek higher yields and take on more risk. Low interest rates allow borrowers to take on more debt. Low interest rates can promote investments that become unprofitable when the economy slows down. A maximum interest rate can prevent these situations from happening. A maximum interest rate caps the risk lenders are willing to take and promotes a deleveraging of balance sheets, so that even low-yielding ventures don’t go bankrupt because of interest-bearing debts.

Issues with the maximum interest rate

A holding fee will cause few difficulties, but a maximum interest rate is more problematic. Insofar as the maximum interest rate affects questionable segments of credit, such as credit card debt and subprime lending, this is beneficial overall. More serious issues can emerge with financing small and medium-sized businesses. Partnership schemes can fill in the gap, but it is hard to predict how that will play out. The maximum yield on loans is zero, making partnerships more attractive, as they can offer higher returns.

There may be objections to the limits Natural Money imposes on consumer credit. Still, there is little doubt that a maximum interest rate can improve consumers’ purchasing power, as borrowers won’t have to pay interest. As a result, there are fewer borrowing options, which may lead to the emergence of black markets. To make illegal schemes unattractive for lenders, lenders who charge interest could lose the money they have lent.

Zero is the only non-arbitrary number, making it more difficult to change the maximum interest rate. That may happen for political or other reasons. The salespeople of usury can find plenty. If it is one, why not two? Zero is a clear line. A positive interest rate, no matter how small, contributes to financial instability. All positive growth rates compound to infinity, so once we start the fire of usury, it will eventually consume us.

A maximum interest rate seems feasible if it is above the rate at which most borrowing and lending occur, thereby limiting the effects on liquidity in the fixed-income market. A maximum interest rate creates room for alternatives, such as private equity and partnership schemes. These alternatives can supplement the fixed-income market and mitigate the effects of the maximum interest rate. A maximum interest rate is beneficial overall if it mainly affects questionable segments of credit, such as subprime lending.

In the case of bonds, the maximum interest rate of zero applies at the time of issuance. Due to economic circumstances or issues with the debtor, the interest rate may rise and enter positive territory. Likewise, governments may issue long-term bonds that may have positive yields if interest rates rise later on. That is not a serious issue, as long as the interest rate was zero or lower at the time of issuance.

A more serious issue is the risk of liquidity problems. When interest rates rise, less credit becomes available at interest rates of zero or lower. Interest rates might increase due to a strong economy with inflationary pressures. There are always economic agents that must borrow at all costs to meet their present obligations, so if they can’t borrow, they might go bankrupt. Businesses and individuals need to deleverage and arrange credit in advance, such as an overdraft facility, with their banks.

Another equally serious question is the profitability of banks with Natural Money. The lending business of banks will likely shrink significantly. The assumption is that risk-free lending will be profitable. But what if it isn’t? In that case, banks may need to lower the interest rates on deposit accounts to a level below the interest rate on short-term government debt. In that case, the cash interest rate may need to be lower than the interest rate on short-term government debt to make it work.

Inherent stability

Ending usury is impossible without investors having trust in the political economy or the political and economic institutions of the polity issuing the currency. The most trusted political economies have the lowest interest rates because their governments are fiscally responsible. Natural Money requires taking it to the next level. With Natural Money, to borrow, the government must find lenders willing to lend in the currency at negative interest rates. The government will be better off borrowing at negative interest rates, which provides an incentive for budgetary discipline. That is the foundation of stability.

Extracting a fixed income from a variable income stream contributes to financial instability. Fixed interest payments can bankrupt a corporation even when it is profitable overall. Interest contributes to moral hazard, as it serves as a reward for taking risks. Investors expect to earn higher yields on riskier debt, so lenders take on these risks. The more uncertain an income source, the higher the interest rate needs to be to compensate for the risk of lending, but the higher the fixed interest rate, the more likely failure becomes, which reveals the destructive consequence of interest being a reward for taking risks.

All parts of the financial system are intertwined. Individual banks can transfer these risks to the system. And so, the risk management of individual agents can increase the overall level of risk in the system. The payment and lending system is a key public interest, so governments and central banks back it. Banks take risks and reap rewards in the form of interest, while public guarantees back up the financial system. The arrangement leads to moral hazard, a mispricing of risk and private profits at the expense of the public. A maximum interest rate can end these problems.

A maximum interest rate causes a deleveraging and a reduction in problematic debts, which has a stabilising effect on the financial system and the economy. Individuals and businesses must already take action before their debts become problematic. Maximum interest rates can distort financial markets. Most notably, there will be fewer options for smaller firms to borrow. Partnership schemes should fill that void.

Interest payments also affect business cycles. The mainstream view is that central banks should raise interest rates during economic booms to curb investment and spending, thereby preventing the economy from overheating. A rosy view of the future prevails during a boom, so higher interest rates seem justified and borrowing continues for some time. When the bust sets in, the picture alters, and an overhang of debt at high interest rates worsens the woes. It would have been better if these debts hadn’t existed in the first place.

That makes a usury-based financial system inherently unstable. Natural Money changes this dynamic. When the economy improves, higher interest rates increase the attractiveness of equity investments relative to debt. That reduces the funds available for lending. The curtailment of credit will prevent the economy from overheating and avoid a debt overhang. When the economy slows, negative interest rates provide stimulus. In the absence of a debt overhang, the economy is likely to recover soon. A Natural Money financial system is inherently stable.

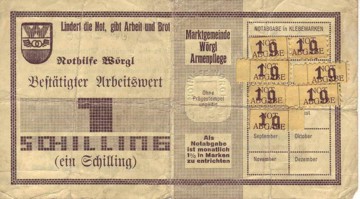

Featured image: 1919 Cover of The Natural Economic Order. Wikimedia Commons.

1. Simon Smith Kuznets, Stephanie Lo, Eric Glen Weyl (2009). The Doctrine of Usury in the Middle Ages. Simon Smith Kuznets, transcribed by Stephanie Lo. An appendix to Simon Kuznets: Cautious Empiricist of the Eastern European Jewish Diaspora.

2. Sekreter, Ahmet (2011). Sharing of Risks in Islamic Finance. IBSU Scientific Journal, 5(2): 13-20.

3. K. Samuelsson (1955). International Payments and Credit Movements by the Swedish Merchant Houses, 1730-1815. Scandinavian Economic History Review.

4. R. Alton Gilbert (1986). Requiem for Regulation Q: What It Did and Why It Passed Away. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.