Turning debt into money

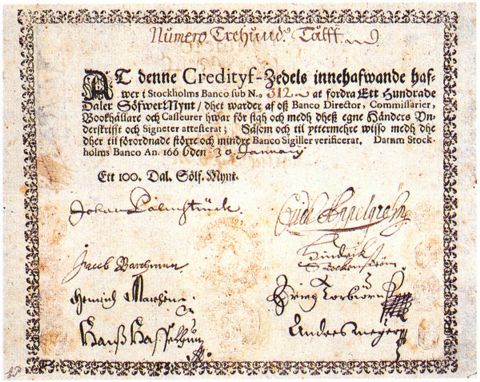

The previous episode about money discussed some imaginary trades between you, a hatter, a lawyer, a barber and a fisherman. It is shown that if people promise to pay this might suffice for payment. So if the fisherman promises you to pay next week for the hat you just made, you could say to the lawyer that you expect the fisherman to pay in a week, and ask her if you can pay in a week too. The lawyer could then ask the same of the barber and the barber could ask the same of the fisherman. If all these debts cancel out then no cash is needed.

In most cases, debts cannot be cancelled out so easily. A hat may cost € 50, legal advice € 60, a hairdo € 30, and the fish € 20. If you are the hatter, you could lend € 10 to the barber and the lawyer could lend € 20 to the fisherman. Perhaps the lawyer doesn’t trust the fisherman because he smells fishy. But if the lawyer trusts the barber and the barber trusts the fisherman then the lawyer could lend € 20 to the barber and the barber could lend € 20 to the fisherman.

That could become complicated quite easily. And this is where banks come in. Banks can lend money because they know the financial situation of their customers. The fisherman can borrow money from his bank to make payments because the bank knows that he has an unstable but good income and a vessel that can be sold for cash if needed.

If the fisherman borrows money to pay for the hat you made, this money ends up in your account. You can use it to pay the lawyer. And so the fisherman’s debt becomes the lawyer’s money until she uses it to pay the barber. People that have a deposit lend money to the bank and the bank is lending this money to those who have a loan, in this case, the fisherman. Depositors trust the bank even though they do not know the people the bank is lending money to.

Most people think of money as coins and banknotes but more than 90% of the money just exists as bookkeeping entries in banks. When a fisherman borrows money from his bank, he can spend it on a hat. This means that the bank creates money and that this money is debt. Most of our money is debt so the value of money depends on the belief that debtors pay back their debts. This seems scary and it keeps quite a few people awake at night.

Some people argue that debts and banking are frauds because they are based on a belief. But banks and debts help to boost trade and production by creating money that doesn’t exist to start businesses that don’t yet exist to make products which will be bought by the people those businesses will hire with this newly created money. Banking and debts are the basis of the capitalist economy.

Banking as bookkeeping

Banking is more or less just bookkeeping and balance sheets. Balance sheets can be used to explain the magic trick banks do, which is creating money. Balance sheets are simple. There are no intimidating formulas, only additions and subtractions. The important thing to remember with balance sheets is that the total of the amounts on the left side must always equal those on the right side.

On the left is the value of your stuff and your money. On the right side is the value of your debts. Your net worth is what remains when you sell all your stuff and pay off your debts. It is on the right side too in order to make it equal to the left side. Your net worth can be a negative value. If that is the case, you might be bankrupt because you can’t repay your debts by selling your assets. The left side is named debit and the right side is called credit. Your balance sheet might look like this:

|

debit

|

credit

| ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

house

|

€ 100,000

|

mortgage

|

€ 80,000

|

|

other stuff

|

€ 50,000

|

other loans

|

€ 30,000

|

|

cash, bank deposits

|

€ 20,000

|

your net worth

|

€ 60,000

|

|

total

|

€ 170,000

|

total

|

€ 170,000

|

When you buy a car, you own more stuff, but also another loan or fewer bank deposits as you have to pay for the car. This is because debit always equals credit. When you drive the car, it goes down in value, as does your net worth, because debit always equals credit. If your salary comes in, your bank deposits as well as your net worth rise because debit always equals credit. If you pay down a loan, the amount in your bank account, as well as the amount of your loan, goes down because debit always equals credit. If debit doesn’t equal credit then you have made a calculation error.

Also for a bank, the total of the amounts on the left side must always equal those on the right side, so that debit always equals credit. Your debt is on the debit side of the bank’s balance sheet. You have borrowed this money from your bank. The bank owns this loan. Your bank deposits are on the credit side of the bank’s balance sheet. The loans of the bank are paid for by deposits. Banks lend money to each other. This may happen when you make a payment to someone who has a bank account at another bank. Your bank may borrow this money from the other bank until another payment comes the other way. The balance sheet of a bank may look like this:

|

debit

|

credit

| ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

mortgages and loans

|

€ 70,000,000

|

deposits

|

€ 60,000,000

|

|

loans to other banks

|

€ 10,000,000

|

deposits from other banks

|

€ 20,000,000

|

|

cash, central bank deposits

|

€ 10,000,000

|

the bank’s net worth

|

€ 10,000,000

|

|

total

|

€ 90,000,000

|

total

|

€ 90,000,000

|

How banks create money

Banks create money. How do they do that? It is easy if you understand balance sheets. Assume that you, the hatter, the lawyer, the barber, and the fisherman all have € 10 in cash. Together you decide to start a bank. You all bring in the € 10 you own so that you all have a deposit of € 10 and the bank has € 40 in cash. The bank allows everyone to withdraw deposits in cash. This is no problem as long as the total of deposits equals the total amount of cash. After everyone has put in the deposit, the bank’s balance sheet looks as follows:

|

debit

|

credit

| ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

cash

|

€ 40

|

your deposit

|

€ 10

|

|

deposit lawyer

|

€ 10

| ||

|

deposit barber

|

€ 10

| ||

|

deposit fisherman

|

€ 10

| ||

|

total

|

€ 40

|

total

|

€ 40

|

First, there was only € 40 in cash. Now there are € 40 in bank deposits too. You might think that the bank created money. Only, that isn’t true because the depositors can’t spend the cash unless they take out their deposits. In other words, the depositors don’t have more money at their disposal than before. If you look at the total, there is still € 40. This is bookkeeping. You have to write down the total twice as debit must equal credit.

But now things are going to get a bit wild. The fisherman comes to you and he wants to buy a hat. The hat costs € 50 but the fisherman has only € 10 in his account. To make the sale possible, the bank is going to do its magic. The fisherman calls the bank and asks if he can borrow some money. The bank grants him a loan of € 40 and puts the money in his deposit account so that he can spend it. And look:

|

debit

|

credit

| ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

cash

|

€ 40

|

your deposit

|

€ 10

|

| loan fisherman |

€ 40

|

deposit lawyer

|

€ 10

|

|

deposit barber

|

€ 10

| ||

|

deposit fisherman

|

€ 50

| ||

|

total

|

€ 80

|

total

|

€ 80

|

Who says that miracles can’t happen? The deposits miraculously increased from € 40 to € 80 so € 40 is created from thin air. There is still only € 40 in cash but the fisherman’s debt created new money. This is how banks create money. And that is only because bank deposits are money. This is all there is to it. So much for the mystery. The fisherman then pays € 50 for the hat. And so it becomes your money:

|

debit

|

credit

| ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

cash

|

€ 40

|

your deposit

|

€ 60

|

| loan fisherman |

€ 40

|

deposit lawyer

|

€ 10

|

|

deposit barber

|

€ 10

| ||

|

deposit fisherman

|

€ 0

| ||

|

total

|

€ 80

|

total

|

€ 80

|

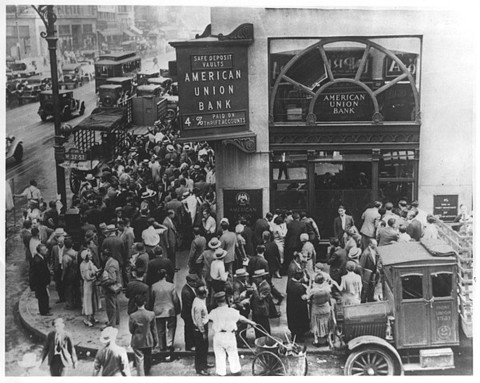

And now comes the dreadful part that keeps some people fretting. Everyone can take out his or her deposits in cash. There are € 80 in deposits and only € 40 in cash. If you go to the bank and demand your € 60 in cash, the bank would go bankrupt, even when the fisherman pays off his loan the next day. You could bankrupt the bank by buying € 50 in fish with cash. If you go to the bank to get € 50 in cash it would not be there so the bank would go bankrupt before the fisherman can pay off his loan with the same cash.

A bank could get into trouble in this way even when debtors repay their debts. Clever minds already figured out a solution. Central banks can print money too. If the European Central Bank (ECB) prints € 20 on a piece of paper and lends this money to the bank, there would be enough cash to pay out your deposit. Banning the use of cash and only using bank deposits for payments would be another option. So, after the ECB deposited € 20 in cash, the bank’s balance sheet might look like this:

|

debit

|

credit

| ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

cash

|

€ 60

|

your deposit

|

€ 60

|

| loan fisherman |

€ 40

|

deposit lawyer

|

€ 10

|

|

deposit barber

|

€ 10

| ||

|

deposit fisherman

|

€ 0

| ||

|

deposit ECB

|

€ 20

| ||

|

total

|

€ 100

|

total

|

€ 100

|

After you pay the fisherman, he can pay off his loan, and the bank will have enough cash to pay out all deposits. The bank can repay the central bank and everything is fine and dandy again. In this case the bank could not meet the demand for cash but the value of cash and loans wasn’t smaller than the deposits (the bank’s debt). After the fisherman pays back his loan and the bank pays back the ECB, the bank’s balance sheet might look like this:

|

debit

|

credit

| ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

cash

|

€ 40

|

your deposit

|

€ 10

|

| loan fisherman |

€ 0

|

deposit lawyer

|

€ 10

|

|

deposit barber

|

€ 10

| ||

|

deposit fisherman

|

€ 10

| ||

|

deposit ECB

|

€ 0

| ||

|

total

|

€ 40

|

total

|

€ 40

|

If banks can’t create money, trade would be difficult. If the hat is € 50, the legal advice € 60, the hairdo € 30, and the fish € 20, and you, the lawyer, the barber and the fisherman all have only € 10, nothing can be bought or sold. If the bank lends € 40 to the fisherman, he can buy a hat from you, you can buy legal advice from the lawyer, the lawyer can buy a hairdo and the barber can buy fish. Debt is the basis of the capitalist economy. Nearly all money is debt, and without debt, the economy would come to a standstill.

How much money can banks create?

The amount of money a bank can create is limited by the bank’s capital, which is the bank’s net worth. Regulations stipulate that banks should have a minimum amount of capital. This is the capital requirement. If the capital requirement is 10%, and the bank’s capital is € 10,000,000, it can lend € 100,000,000, provided that there are enough deposits. If the bank makes a loan, a new deposit is created. If the deposit leaves the bank, the bank must borrow it back from another bank or cut back its lending. That is because debit must always equal credit.

|

debit

|

credit

| ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

mortgages and loans

|

€ 70,000,000

|

deposits

|

€ 60,000,000

|

|

loans to other banks

|

€ 10,000,000

|

deposits from other banks

|

€ 20,000,000

|

|

cash, central bank deposits

|

€ 10,000,000

|

the bank’s net worth

|

€ 10,000,000

|

|

total

|

€ 90,000,000

|

total

|

€ 90,000,000

|

When a deposit leaves the bank, it ends up at another bank. The other bank can use it for lending, provided that it has sufficient capital. There may be a reserve requirement, which is a minimum of cash and central bank deposits the bank must hold. If the reserve requirement is 10%, the bank can lend out as much as ten times the amount of cash and central bank reserves it has available. In the past, reserve requirements were important as people often used cash and could go to the bank to demand their deposits in cash. For that reason banks needed to hold a certain amount of cash.

Featured image: Deutsche Bank building CC BY-SA 4.0. Raimond Spekking. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.