Introduction

In 2022, Vladimir Putin ordered Russian troops to invade Ukraine in a so-called special military operation known as the Ukraine War. It is tempting to see Putin as the sole cause of the war, but there is more to this conflict than the godfather of a mobster government trying to expand his turf. Even Adolf Hitler had good reasons for tearing up the Versailles Peace Treaty and occupying the Rhineland. What he did next was less reasonable, and it culminated in mass murder. After World War II, the Allies realised that without the unreasonable Treaty of Versailles, the war probably wouldn’t have happened. Leaders make mistakes all the time. Western leaders ignored Russian interests by expanding NATO into former Soviet territory and promising NATO membership to Ukraine.

Giving in to Putin’s demands will embolden him to invade other countries. You don’t have to doubt that. Donald Trump, like a veritable peace dove, was willing to give the gangster in the Kremlin what he claimed to desire, but Vlad the Empirebuilder sniffed weakness and now thinks he can win the war. Geopolitics works like gangster warfare. The West operates by the same logic. Iraq didn’t pose a threat to the United States. The businesspeople behind the move hoped to profit from looting the country. China plans to invade Taiwan, and once it has done so, a new objective will undoubtedly pop up in the heads of the imperialists in Beijing. Meanwhile, the madman in the White House has set his eyes on the Panama Canal, Greenland and Canada. So, will there ever be peace?

Blaming the West or Putin for the Ukraine war doesn’t prevent the next war. There are always conflicts brewing, such as those between India and Pakistan, Israel and Iran, and Thailand and Cambodia. There is always something to fight about. The Ukraine conflict has a long history, as do many other conflicts, and the motives of he warring parties always appear honourable. Putin’s case for invading Ukraine is better than the US’s case to invade Iraq. Leaders tell stories about national greatness or the threats posed by other states to send us to war. Had the Soviet Union still existed, a state founded on a story of a brotherhood of peoples that repressed nationalism, the Ukraine War would never have happened. That points to both the cause and the solution. We can end warfare by uniting as one humanity with a single story.

Historical background

Between 800 and 1240 AD, the Ukrainian capital, Kyiv, was the centre of Kievan Rus, a state founded by the Viking traders who sought a land route to the Mediterranean. By 1240, the Mongols overran the area. When Mongol power waned by 1400, a new Russian state emerged around Moscow, while Ukraine became part of Poland. Crimea and the surrounding territories became part of Turkey. As a result, Ukraine became separated from Russia and developed a separate culture and language. Polish and Turkish power declined from the seventeenth century onwards, and Russia filled the void. By 1800, Russia had become a large empire controlling most of Ukraine.

During World War I, the Russian Empire collapsed, and a civil war followed the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. By 1922, the communists had won and held most of Ukraine. In the late 1920s, the Soviets forcefully collectivised farms. Farmers lost their land and ended up in prison labour camps. Agricultural output dropped, leading to a famine and the deaths of three to five million people. In 1939, Hitler and Stalin made a pact. They divided Poland, and the Soviet Union acquired Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Western Ukraine. When Germany invaded the Soviet Union in 1941, some Ukrainians saw the Germans as liberators, but many more fought in the Red Army. After the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, Ukraine became independent. Crimea remained strategically important to Russia as it was the home of the Russian Black Sea fleet.

When the Soviet Union retreated from Eastern Europe, NATO leaders promised Mikhail Gorbachev that NATO would not expand into its former sphere of influence.1 Eastern European countries were eager to join NATO. Once liberated from Soviet oppression, they sought security guarantees against their neighbour, Russia, which joining NATO could provide. Several policymakers in the West believed NATO expansion would be a historic mistake. Russia could see it as a violation of the promises made, which could undermine cooperation with Russia.2 NATO expansion proceeded nonetheless. The collapse of the Soviet Union broke the Russian spirit and national pride. Russia had been an empire, and the Soviet Union was a world power. It was all in shambles.

Vladimir Putin worked for the Soviet secret service, the KGB, for sixteen years. After leaving the Secret Service in 1991, he worked for the mayor of Saint Petersburg, where he oversaw the disappearance of precious metals and food, leading to allegations of corruption.3 Later, Putin joined President Boris Yeltsin’s staff. In 1998, Yeltsin appointed him director of the intelligence service FSB, the successor of the KGB. On 9 August 1999, he became Prime Minister.

One month later, a series of terrorist attacks took place inside Russia, which the FSB attributed to Chechen militants, while the evidence indicates that the FSB was behind it. State Duma speaker Gennadiy Seleznyov announced that another bombing had occurred in Volgodonsk, while that bombing had yet to happen. In Ryazan, the local police apprehended FSB agents planting bombs. As Putin had been the FSB’s head until a month before these attacks, the obvious question is whether he had ordered them. His being the kind of guy who would do such a thing doesn’t count as proof, but Putin is the kind of guy who would do such a thing. And so, the conductors of an independent investigation either died mysteriously or ended up in prison.

In any case, Putin seized on the opportunity. He vowed to go after the Chechen terrorists, which made him popular with the Russian people. The terrorist attacks became a pretext for a long and bloody war in Chechnya. A few months later, Yeltsin stepped down and appointed Putin his successor. Putin pledged to restore Russia’s prestige and sphere of influence. He eliminated the oligarchs who opposed him and stripped them of their possessions. His opponents, also those who lived abroad, had a significantly higher death rate than average citizens, attributable to causes like falling out of windows or running into nerve gases. The surviving oligarchs had to pay taxes, which improved the state’s income.

Vlad the Empirebuilder sees the former Soviet territories as a primary interest to Russia and seeks influence or dominance in that area. In 2005, despite corruption, voter intimidation, election fraud and the poisoning of the pro-Western candidate Viktor Yushchenko, Ukraine held free elections due to a popular uprising, much to the dismay of Putin, who had hoped to retain control of the country with the help of his favourite, Viktor Yanukovych. Most other Soviet republics remained within Russia’s sphere of influence, except Georgia, which aspired to EU and NATO membership. Russia then invaded Georgia in 2008.

Prelude

Since its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukraine has had a multi-party system with numerous corrupt political parties in which oligarchs play a central role. The country became almost evenly split into two political blocs. One sought cooperation with the West, and another aimed for closer ties with Russia. People in the West and the centre of Ukraine favoured the Western-oriented bloc, while people in the East and the South generally favoured the Russia-oriented bloc. That coincided with the languages spoken. People in the East mostly spoke Russian, and people in the West spoke Ukrainian.

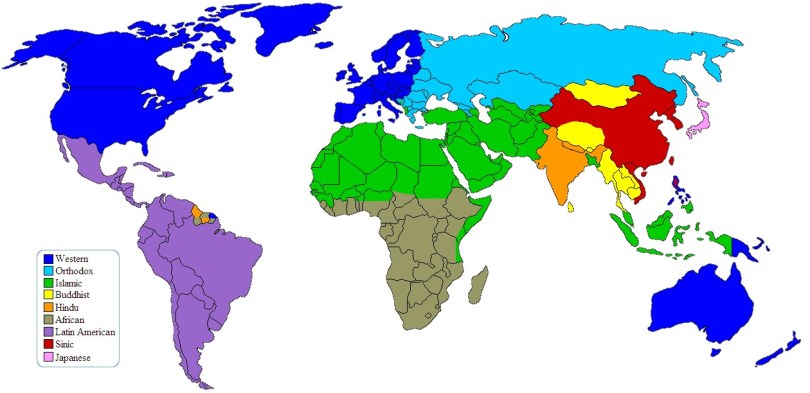

Many living in eastern Ukraine spoke Russian, felt a connection to Russia, and desired friendly relationships with Russia. Many living in the West thought they were Ukrainian, felt unrelated to Russia, and hoped to become part of the West and be free from Russian influence. It was a recipe for trouble, which the imperial powers, the United States and Russia, sought to exploit. Samuel Huntington called Ukraine a cleft country as these blocs identify with separate civilisations. Ukraine had plans to join NATO. In 2008, Putin warned Moscow would view that plan as a direct threat to Russia’s security.4

After fair elections, Putin’s favourite, Viktor Yanukovych, became president in 2010. By 2013, there was strong support for an economic treaty with the European Union (EU) in Parliament. After lengthy negotiations, a deal was in the making. Then, Yanukovych decided not to sign a political association and free trade agreement with the EU and to seek closer ties with Russia instead. Russia was Ukraine’s largest trading partner, and Putin had offered loans on favourable conditions while threatening to harm the interests of the Ukrainian oligarchs and politicians if they rejected his proposal.5

Protests erupted, calling for the resignation of the president and the government. The demonstrations were initially peaceful, but President Yanukovych responded with a police crackdown that included the use of snipers. The protestors held out for months and fought back with chains, sticks, stones, petrol bombs, a bulldozer and firearms. At some point, the police could no longer defend themselves from protesters’ attacks. In the end, 108 civilians and 13 police officers had died. The Euromaidan protests led to the ousting of the government, and President Yanukovych fled. Most Ukrainians didn’t want to sever ties with Russia at that point, as Ukraine relied on cheap gas from Russia.5 After the Maidan Revolution, pro-Russian protests and uprisings erupted in Crimea, the Donbas and Odesa.

Pro-democratic groups had started the Maidan Revolution. Most participants were ordinary citizens. However, the violence of the well-organised fascists, which included the use of snipers, probably decided the outcome. The Ukrainian fascists have a long history which traces back to the partisan movement from the 1940s. After the Maidan Revolution, fascists patrolled the streets of Kyiv. They also provided fighters for the war against Russia-backed separatists. Among them was the Azov regiment, a group of 900 fighters with Nazi sympathies.6 Their bravery on the battlefield at a time when the regular army had difficulty defending Ukrainian territory made the far-right more respected in Ukraine.

Russia claims that the Maidan Revolution was a Western-sponsored coup to overthrow a legitimate government. Yanukovych had become President after fair elections. Between 1991 and 2014, the US spent $ 5 billion to support civil society and NGOs aiming at strengthening democracy, anti-corruption efforts, and economic development. These groups had played a central role in starting the protests. Had the far-right not come to their aid, President Yanukovych might have been able to subdue the demonstrations with force.

And so, Putin sees foreign aid money as interference and a threat to Russia. After pro-democratic protests in Russia, he made Russian NGOs receiving money from abroad subject to a foreign agent law and closed their operations in Russia. Since the Orange Revolution in 2004, Putin began investing in increasing Russian influence abroad.7 It included interference with the 2016 US elections.8 After the Maidan Revolution, the Obama administration chose not to antagonise Russia after learning the lessons of Russia’s war with Georgia in 2008. The previous Bush administration had provided Georgia with money and weapons in an attempt to build a strategic bridgehead in the southern Caucasus region, provoking Russia to invade Georgia.7

Ukraine War

Ukraine was drifting away from Russia and aligning itself with the West. Most Ukrainians don’t want to live under Putin’s rule, but they also hoped for a good relationship with neighbouring Russia. That is why they elected Volodymyr Zelensky. A Ukrainian NATO membership would endanger that. Putin believed Ukraine was of crucial interest to Russia. Losing Ukraine would be a damaging geopolitical loss for Putin. The Russian invasion of Crimea and the Donbas insurgency had soured Russian-Ukrainian relations. There had been a truce, but there was regular shelling of civilian areas.9 The Donbas attracted Ukrainian far-right fighters seeking combat experience. Russia-backed separatists have reported terrorist attacks with a total of 1,000 fatalities between 2015 and 2021.10

Zelensky had won the 2019 elections by promising to seek peace with Russia. The far-right blocked these plans by promising there would be riots and that Zelensky might be killed.11 A return of Ukraine to the Russian sphere of influence was not to be expected. The truce with Russia was not more than a truce for both parties, as Ukraine intended to regain its lost territories while Putin hoped to bring Ukraine under Russian influence. Ukraine was building its military and seeking NATO membership. Although NATO considers itself a defensive alliance, it is part of the Western sphere of influence, and Putin sees it as a coalition against Russia that could threaten Russia’s security.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, few expected the Ukrainian army would hold out for more than a few weeks. In the first days of the war, Zelensky rejected an evacuation offer from the United States, saying he needed ammunition, not a ride. Street fighting in Kyiv was about to commence. Zelensky, who had been an actor previously, unified the nation and extracted weapons and other support from his Western allies. He had played the Ukrainian President in a comedy previously. Fiction has become a reality. Or is reality fiction?

There were peace talks during the first months of the war. Both Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky and Russian President Vladimir Putin seemed willing to make concessions. Western powers blocked a peace deal, fearing the agreement would reward the aggressor state, Russia. Western powers also hoped to weaken Russia.12 The discovery of the Bucha massacre in early April, in which Russian troops had murdered over four hundred civilians, was another reason the peace talks failed.13 For three years, the war dragged on. Ukraine needed Western support to keep its army in the field.

It was a stalemate, with Russia making a few territorial gains at the expense of massive losses in military personnel. In 2025, Donald Trump became President of the United States. He initially held a more favourable view of the Russian position and went as far as parroting the Russian propaganda narrative that Ukraine had started the war. The man in the White House took upon himself the role of peace dove and tried to broker a peace deal with Russia by pressuring Ukraine into accepting the loss of territory and giving up NATO membership. The sudden change in American policy left America’s European allies in disarray, prompting them to express their support for Ukraine. Trump soon found out that what his European allies told him was all true, and that the man in the Kremlin wasn’t at all interested in peace.

Clash of civilisations

Geopolitical actors act as gangs, defending and expanding their turf. It is insightful to paint the picture of the Ukraine war as gang warfare, so Putin’s mafia state attacking a state backed by the US mobster state run by neoconservative gangsters and the military-industrial complex, which, amongst others, invaded Iraq to loot its oil. And by the way, far-right thugs in Ukraine, the so-called Nazis, whom Putin was harping about while having Nazi mercenaries from the Wagner Group fighting on the Russian side, have prevented a peace deal with Russia. Meanwhile, Ukraine alleges that China is supporting the Russian war effort, while China claims it can’t accept Russia losing the war.14

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Neoconservative view won out, as the United States found itself the hegemon in a unipolar world. It emboldened the Neoconservatives’ aggressive attitude and pursuit of global dominance. US planners aimed to prevent the emergence of a rival power in any part of the world. They hoped to establish a global order, the New World Order, which George H.W. Bush mentioned in his speeches as a peaceful cooperation between nations. This arrangement would allow other countries to pursue their legitimate interests while deterring them from aspiring to a larger regional or global role or challenging US leadership.11

A single world order can bring peace or at least limited warfare. The Romans pacified the Mediterranean. From behind the desks of the geopolitical planners in the United States, it may have seemed a marvellous idea and an excellent business opportunity for the military-industrial complex. It brought the Iraq War, with hundreds of thousands of fatalities. It has always been the prerogative of the hegemon to ignore the subjected people. The Romans never considered how the Gauls felt about Roman occupation. The resentment about the West’s colonial past and military interventions is understandable, but the end of Western dominance will not end warfare. Nothing will unless we have a single world order.

The clash-of-civilisations view doesn’t provide a workable alternative. Ukraine and Russia are Christian Orthodox and Slavic, but most Ukrainians choose the West. The same applies to Taiwan and a few other countries that share China’s Confucianist heritage, such as Japan and South Korea. The Clash of Civilisations predicted that these countries would seek leadership from the leading nations of their respective civilisations, Russia and China. The world has become closely integrated, so separating this globalised world along civilisational lines makes little sense. China’s growing economic and military power makes Neoconservative thinking increasingly risky. China asserts its sovereignty over Taiwan and the South China Sea, using force to back up its claims. If China’s neighbours feel threatened and seek an alliance with the United States, that could be another path to World War III.

Gang warfare

Geopolitical actors act as gangs, defending and expanding their turf. It is insightful to paint the picture of the Ukraine war as gang warfare, so Putin’s mafia state attacking a state backed by the US mobster state run by neoconservative gangsters and the military-industrial complex, which, amongst others, invaded Iraq to loot its oil. And by the way, far-right thugs in Ukraine, the so-called Nazis, whom Putin was harping about while having Nazi mercenaries from the Wagner Group fighting on the Russian side, have prevented a peace deal with Russia. Meanwhile, Ukraine alleges that China is supporting the Russian war effort, while China claims it can’t accept Russia losing the war.15 The major powers are all making their cynical calculations.

Humans operate in groups. It is human nature, so the gang is our default political organisation. This type of establishment dominated most of human history and still exists today in the form of warlords, militia, drug cartels, and street gangs. States have proven to be effective in repressing violence within their borders. If the order breaks down, gangs will run most places.16 Gang leaders see themselves as public benefactors, on par with eminent leaders of states. And so do their followers. As order is retreating, we now witness the rise of far-right gangster governments in the West with leaders who engage in criminal acts. In gangs, peace also works best, but they regularly fight.

In a unipolar world, where one power dominates, most countries fear and respect the hegemonic power. A hegemonic power can provide order, much like a police officer, or it can be a big bully that attacks others. The United States was the hegemon between 1990 and 2020. Other countries didn’t challenge that position. It allowed the United States elites to develop delusions of grandeur and invade Iraq because of a belief in the superiority of Western values. The Neoconservative planners inside the US government thought Iraq would miraculously turn into a liberal democracy after the invasion.17 It was wishful thinking, promoted by delusions of grandeur about the superiority of Western civilisation. Probably, the business case also seemed profitable.

In a world with two major powers, a stable situation can emerge. During the Cold War, there was mutual assured destruction (MAD) in case of a nuclear war. Still, the United States and the Soviet Union were on the brink of nuclear war during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis and again in 1983, when Ronald Reagan’s aggressive rhetoric made the Soviet leadership believe the US would attack. They put their nuclear forces on high alert. Both on the Soviet and US sides, warning systems for incoming enemy missiles have malfunctioned and sounded the alarm. The soldiers watching the alarms detected red flags, suggesting these alarms were false. And so, we were lucky to come out of the Cold War alive. In a multipolar world, alliances shift, and a stable situation is less likely to emerge. That is what powers like China and Russia are aiming for.18

On the eve of World War I, Europe was a multipolar continent with five major powers and shifting alliances. The future of the multinational Austrian-Hungarian Empire was in peril as the nationalism of the different peoples living in it gradually undermined it. After a Serbian nationalist assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the leadership of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire believed it had to eliminate the Serbian threat. Russia felt it had to support its ally Serbia to prevent it from being overrun by the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. Germany felt threatened because its foes, France and Russia, surrounded it. Germany saw no option but to back its ally, the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. France and Great Britain backed Russia because it was their ally, and Germany their foe. And so, a simple assassination plunged Europe into a war that killed over ten million people. We are drifting toward a multipolar world with several major powers, hence, a politically less stable one.

Conspiring for world peace

Before World War I, the socialist movements declared their opposition to war, which meant workers killing each other for their capitalist bosses. Once the war had started, most socialists and trade unions backed their government and supported their country’s war effort. The workers would have been better off if they had united and refused to fight. So, why did they go to war nonetheless? You and the other are better off if you don’t fight. But you don’t know what the other will do. If you don’t fight, the other might kill you. Workers in France were uncertain about the actions of their German counterparts. If the latter had joined the army, but not the French, then Germany would have overrun France. Furthermore, nationalist stories about pride and heritage proved more inspiring than the rational appeal to the self-interest of the international proletariat.

After World War II, the elites of the West tried to prevent future wars by promoting the cooperation of nations in international institutions dominated by Western elites like the United Nations, the World Bank, and the IMF. Nationalists and socialists distrusted the capitalist and internationalist Western elites, who were the primary beneficiaries. Still, a single world order is a requirement for permanent world peace. Nowadays, Western power is in decline. A peaceful world order doesn’t appear to emerge anytime soon, not from peasants and workers of all nations joining hands, nor from the secretive scheming of the elites. Humans have been incapable of bringing permanent peace on their own and probably remain incapable of it in the foreseeable future. Perhaps the survivors of World War III will come to their senses after having seen billions of people die, but there is no guarantee that they will.

Featured image: Destroyed Russian tank near Mariupol. Ministry of Internal Affairs of Ukraine. Wikimedia Commons.

Latest revision: 5 August 2025

1. NATO Expansion: What Gorbachev Heard: Declassified documents show security assurances against NATO expansion to Soviet leaders from Baker, Bush, Genscher, Kohl, Gates, Mitterrand, Thatcher, Hurd, Major, and Woerner. George Washington University (2017). [link]

2. NATO expansion: a policy error of historic importance. Michael MccGWire. Review of International Studies (1998). [link]

3. Putin’s Career Rooted in Russia’s KGB. David Hoffman (2000). Washington Post. [link]

4. Putin warns Nato over expansion. The Guardian (2008).

5. A US-Backed, Far Right–Led Revolution in Ukraine Helped Bring Us to the Brink of War. Jacobin (2022). [link]

6. Profile: Who are Ukraine’s far-right Azov regiment? AlJazeera (2022). [link]

7. Did Uncle Sam buy off the Maidan? Marc Young (2015). Die Zeit. [link]

8. Fact Sheet: What We Know about Russia’s Interference Operations. German Marshall Fund of the United States.

9. UN report on 2014-16 killings in Ukraine highlights ‘rampant impunity’. United Nations (2016). [link]

10. Ukraine-Russia Crisis: Terrorism Briefing. The Institute for Economics & Peace (2022).

11. Why Zelensky won’t be able to negotiate peace himself. Ted Snider (2024). Responsible Statecraft.

12. ‘We want to see Russia weakened’: Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin says he wants Putin’s forces depleted so he cannot repeat what he has done in Ukraine during his Kyiv trip. Daily Mail (2022). [link]

13. The Grinding War in Ukraine Could Have Ended a Long Time Ago. Branko Marcetic. Jacobin (2023). [link]

14. Defense Planning Guidance (1992). George Washington University. [link]

15. China tells EU it can’t accept Russia losing its war against Ukraine, official says. Nick Paton Walsh. CNN (2025) [link]

16. The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution. Francis Fukuyama (2011). [link]

17. What the Neocons Got Wrong. Max Boot. Foreign Affairs (2023). [link]

18. China-Russia ties strengthen, accelerate multipolar world. Andrew Korybko (2025). GlobalTimes.cn. [link]