George Orwell worked at the British Ministry of Information during World War II. From 1941 to 1943, Orwell worked for the BBC, broadcasting propaganda talks to India. His wife worked in the ministry’s censorship division. It became the model for the Ministry of Truth in Orwell’s world-famous novel Nineteen Eighty-Four.1 The Ministry of Truth’s motto was, ‘Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.’ We always learned that the BBC told us the truth, but that was part of the propaganda. The alternatives were Nazi Germany and, later the Soviet Union. These states had their own propaganda. No social order is objectively the best. We cooperate by believing in stories, such as religions and ideologies. If we stop believing them, our societies fall apart. Every order needs a story. That is why we have propaganda and censorship.

The Cold War was a decades-long standoff between the West and the Soviet Bloc. Two opposing stories and corresponding political-economic systems competed for global dominance: businesses aiming for profit, with their funny advertisements selling harmful products like cigarettes, versus the humourless communist cadres who wouldn’t kill us for profit but only for their socialist ideals. The Cold War included a propaganda war. Western propaganda touted our freedom to choose a cigarette brand and flavour as a way to express our personality. Smoking a brand made us feel special. The communists claimed cigarette manufacturers kill us for profit. People in communist countries had no brands or flavours to choose from, so they didn’t feel special or unique. However, they held spectacular military parades every year, in which they flaunted their tanks and missiles.

During the Cold War, the BBC cooperated with the UK government to discredit the radical left and promote moderate social democratic views within the Labour Party. The mainstream media, including the BBC, were part of that order, so they didn’t tell us everything. And secret services planted news stories,2 or employed the experts you heard and saw on the radio and television.3 You can never be sure the news you read or hear is entirely factual and propaganda-free. Today, the trust in the liberal order is declining. Its story fails to convince us, not only because of the lies, but also because of the propaganda promoting a new fascism, which comes with even more lies.

The BBC and other mainstream media rarely spread fake news, but they sometimes omit relevant facts and perspectives, which you might call lying by omission. The Dutch public broadcaster NOS reportedly passed every fact check for five years.4 The far-right criticised the selection of news stories and how the NOS presented them. The NOS has regularly reported on far-right violence but barely gave attention to the ethnicity of criminals. The stories you believe in determine which facts you deem worthy of reporting. A Catholic might want to learn about an apparition of the Virgin Mary, while others don’t.

In Hungary, a far-right leader and his cronies control most of the media. Fascists dislike factual reporting and diversity of opinion more than liberals. The Hungarians are happy with their leaders, who are more like gangsters than bureaucrats, because they keep the immigrants out. We are religious beings and need stories to believe in. What the relevant facts are doesn’t always depend on opinions. While the debate centres around immigration, more serious issues don’t receive attention. The historian Yuval Noah Harari compares the advent of artificial intelligence with a wave of billions of AI immigrants. They don’t need visas. They don’t arrive on boats. They come at the speed of light. They take jobs. They may seek power. They may replace us. And no one talks about it.

While the West has tried to come clean about its colonial past and slavery, what happened after World War II was as danming. Under the guise of fighting communism, the United States and its intelligence services committed atrocities and destabilised countries by supporting insurgencies. The Cold War encompassed a proxy war between the United States and the Soviet Union in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. The estimated death toll of these conflicts could exceed ten million. The United States didn’t start all these conflicts, nor was the US responsible for all the deaths, as the communists played it as dirty, but the interventions of the United States caused many of these conflicts or lengthened them.

Western leaders used false flags or invented stories about weapons of mass destruction and spread them via the media. The US started the Vietnam War after falsely claiming the North Vietnamese navy had attacked US ships in the Gulf of Tonkin. The US also invaded Iraq after falsely claiming it had weapons of mass destruction. Western leaders made unprovoked aggression look like a war of liberation or promoted a blockade that starved civilians as a humane effort to pressure an abusive government with sanctions. The former US Ambassador to the United Nations, Madeleine Albright, once said sanctions on Iraq were worth the deaths of half a million Iraqi children, which was the estimated death toll.

Also in the West, journalists aren’t safe from prosecution. In 2006, Julian Assange founded WikiLeaks, which published documents obtained by hackers, thereby exposing human rights violations by the US secret services. The United States considered these revelations a national security threat. Assange spent seven years in the Ecuadorian embassy and five years in a British prison. On 1 November 2019, UN Special Rapporteur on torture, Nils Melzer, wrote, ‘While the US Government prosecutes Mr. Assange for publishing information about serious human rights violations, including torture and murder, the officials responsible for these crimes continue to enjoy impunity.’5 In 2022, several global media organisations urged the US to end its protection of Assange as it threatens free expression and freedom of the press.6

In 2024, Assange came free after pleading guilty in a US court.

Every social-political order comes with a story explaining why it is the best. Without a good story, we can’t have an order. The foundations of our orders are stories. Most of the time, revolutions and civil wars are worse than dealing with the omissions and falsehoods in the stories that hold the existing order together. But not always. That is why revolutions do happen, but are rare. But as long as we don’t believe the same stories, we will continue to fight each other. The leadership of China and Russia don’t believe in democracy, and no form of government is objectively the best. The orders we have today are the outcome of a competition. The success of an order depends on the circumstances.

In today’s globalised world, there are several competing stories. There is a Christian story, an Islamic story, a socialist story, numerous nationalist stories, a story about slavery and the civil rights movement, a conspiracy theorist’s tale, the story of indigenous peoples, a Hindu story, a Chinese story spanning 2,000 years of greatness, and many others. Often, these stories figure in identity politics, so Chinese like tales about the greatness of China. Finally, there is a liberal story of individual freedom centred around the Magna Carta, the European Enlightenment, the Glorious Revolution, the American and French Revolutions, universal suffrage, and the overcoming of fascism in World War II, where D-Day, rather than Stalingrad, serves as the hallmark event. Children in the West learned it at school. It is a skewed version of history to explain why the liberal order is the best.

These stories are falling apart in this globalised world, including the liberal one. They cannot unite us, and that will lead to more wars and conflicts. The Magna Carta and the Glorious Revolution mean nothing to Chinese, Indians or Africans who look at a colonial past of oppression and exploitation. Others show little interest in China’s rich history or the stories of the indigenous peoples of the Americas. The Hindu caste system makes little sense unless you are a Hindu. We are imaginative creatures and invent new stories, such as the Earth being flat, and a conspiracy existing in the sciences to make us believe the Earth is a sphere. Some believe in it, adding to the confusion. Believing different stories will ruin us. Freedom of opinion is overrated. We need a story that can inspire and unite us all, one that is so spectacular and wonderful that we forget about all the others, and one that is true, so that we don’t need propaganda to believe it.

Latest revision: 24 June 2025

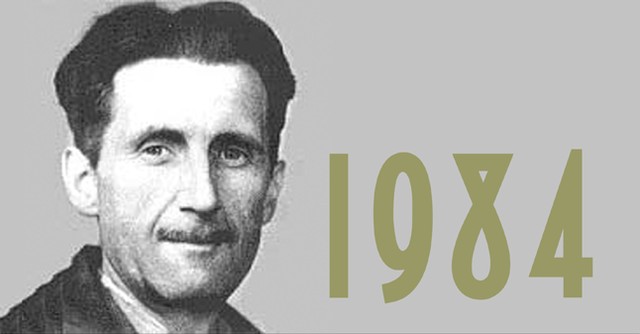

Featured image: 1984 and a photo of George Orwell. Public domain.

1. Orwell, 1984 and the Ministry of Information. Dr Marc Patrick Wiggam. School of Advanced Study, University of London (2017). [link]

2. Nederlandse media drukten artikelen af die waren geschreven door veiligheidsdients BVD. Bart FunnekotterJoep Dohmen (2023). NRC.

3. Geheime diensten gebruiken ‘onafhankelijke experts’ om publiek debat te sturen. Sebastiaan Brommersma (2024). Ftm.nl.

4. Mediabiasfactcheck.com. Netherlands Radio and Television Association (NOS) – Bias and Credibility. (2023).

5. UN expert on torture sounds alarm again that Julian Assange’s life may be at risk. United Nations (2019). [link]