Marlboro Red

In the 2000s, it struck me that nearly all empty cigarette packages dumped on the street were of Marlboro Red. And so I began to pay attention. There were one or two Camels and a few others, but almost all were Marlboro Red. Marlboro Red is the most popular brand. Its market share in the Netherlands is nearly 30%. The second-largest brand has a market share of under 10%. But if you had to make a guess based on discarded empty packages, you would think Marlboro Red had a market share of 95%. It was not scientific research, but my observation and my wife’s. We made jokes about it. We didn’t make tallies, but it was like that. Cultural differences are a big issue. That I had already learned as a student. Marlboro Red smokers often dumped their garbage on the spot, while other smokers rarely did. So, if you’re looking for a jerk, check who’s smoking Marlboro Reds.

You might think that littering isn’t that bad if you compare it to the horrors of warfare, dumping chemicals, the abuses in the meat and dairy industries, and the cutting down of rainforests. Still, disrespect for Creation and God begins with littering. It is also a matter of upbringing, thus culture. Some countries are clean, while others are a mess due to people disposing of their garbage wherever they see fit. And so, it’s pretty easy to spot jerks. Those who litter are. Jerkdom is part of a culture of not caring. We buy the products of corporations that dump chemicals in the ocean and complain about the poisoned fish we eat. There are worse offences. But it starts with littering. Next comes graffiti, which only those who make it consider art. Then comes destroying property. If you want to go further and cause more harm, you might consider buying something, such as new clothes.

If 30% of the people dump 95% of the garbage, the remaining 70% is responsible for only 5%. Marlboro Red smokers were 44 times as likely to dump their trash on the street as other smokers ((95/30) / (5/70) = 44), a striking conclusion. It is not a coincidence because the sample was large enough to make the finding statistically significant. It is more complicated to do this investigation today. You still find cigarette packages on the street, but it is hard to identify the brand name among the scary pictures of cancers and other horrible diseases you get from smoking. Marlboro Red smokers differ from other cigarette smokers. You can call it culture. Culture can explain the deviant behaviour of groups of people who share common characteristics, such as smoking Marlboro Red.

The Marlboro Man embodies careless living in a consumerist society, which apparently includes discarding one’s garbage on the spot. Our brand choices reveal a great deal about our personalities, so marketers have done their jobs well. A politically correct person would say I am stigmatising Marlboro Red users. There could be something wrong with my sample. The sample may have flaws, as I live near a train station where young people gather, but I have also noticed this elsewhere. The difference is so stark that it can’t merely be an error in the sample. Even if the sample correctly reflects reality, perhaps only 0.1% of smokers discard their cigarette packages on the street, so only a tiny minority of 4.4% of Marlboro Red smokers might do so. Perhaps that is correct, or perhaps not, but 44 times as much is an eye-popping difference.

If you intend to tackle the problem of littering cigarette packages and have a limited budget, target Marlboro Red users to achieve the maximum result. Otherwise, you are wasting money. And who wants to waste money? Okay, stupid question. Plenty of people buy Rolex watches. I envision Marlboro Red smokers as jerks who don’t care, thus people who might piss through your letter box, or throw fireworks in it. That is what I imagine, but I might be wrong. Perhaps they are people like you and me, who might be friendly, own a dog, have a job, and look after their neighbours. Reality never ceases to surprise me. If I meet an individual, this person usually doesn’t conform to my prejudices about the groups to which he or she belongs. A group consists of individuals, and although they may share common traits on aggregate, each individual is very different. And there are behaviours like littering that occur more in certain groups than others. Our prejudices about groups have a basis in reality. Still, our prejudices aren’t reality. If you only see Marlboro Red packages on the ground, you may imagine that Marlboro Red smokers are all littering jerks who don’t care. However, it could be a minority, a small minority even.

Can I trust my dentist?

How do cultures emerge and develop? History and circumstances go a long way in explaining that, as the following example illustrates. When I go to a general practitioner, I trust this person. When I visit the dentist, I have more doubts because of my personal experiences and those of others. General practitioners and dentists are similar medical professions. In the Netherlands, a general practitioner doesn’t benefit from the advised treatments, while a dentist does. You have to trust medical professionals, but you can’t always. In a free market, doctors will prey on desperate people. To prevent dental professionals from taking advantage of me too much, I see the dentist only once a year rather than twice, which is the generally accepted guideline. So what happened?

As a child, I had the same dentist for over fifteen years, an old-fashioned one for peasants like me who didn’t propose treatments unless they were necessary. He told me I could wear braces, but it wasn’t necessary for my teeth’s health. I didn’t care about looking perfect, so I still live with the consequences, but they have never bothered me. After all, I wasn’t entertaining a career that would put me at risk of appearing on television.

After leaving my parental home, I selected a new dentist. The first thing he did was take X-ray pictures. Then he said a cavity was developing underneath one of the fillings. Well, what a coincidence. That had never happened before. And coincidences are suspicious, and much more than my suspicious mind could imagine back then. Then the dentist showed me the picture and pointed at a dark spot. There was another filling with a dark area beneath it, and I said, ‘You can see a similar blot here.’ He replied, ‘That is something different.’ I am unqualified to evaluate these X-rays, but both areas were similar, so the dentist lied. Had he not shown me the photograph, I would have believed him. It made me suspicious and overly critical of what dentists were doing.

Before he could treat my tooth for the supposed cavity, I came up with a lame excuse and selected another dentist. A few years later, I had a colleague who had married a dentist. She previously had lived in the same neighbourhood. Her husband was in training at the time. And so, she had been seeing another dentist, who happened to be that one. She told me she had had a row with him. I wasn’t the only one who had smelled a rat there. Her husband was a dentist-in-training, so she probably had valid reasons for quarrelling.

That was a peculiar coincidence indeed. What are the odds of her having the same dentist, given that her husband was a dentist in training, which would provide evidence to support my suspicions being well-founded? Thirty years later, the tooth and the filling were still in place. I later moved again and found an old-fashioned dentist. He was like my first dentist, so I trusted him. He often performed dental cleaning. That usually took ten minutes, and it cost € 21. After ten years, he joined a practice with some other dentists. Shortly after that, he retired.

My next dentist didn’t perform the dental cleaning. Instead, he sent me to a dental hygienist. That treatment lasted twenty-five minutes and was a lot more expensive. Instead of € 21, I paid € 62. Standards do change, but I doubted the sudden need for 150% more cleaning. But if my dentist advises the treatment, who am I to disagree? After all, he is the expert. It is best to accept the assessment of medical professionals unless you have proof they are wrong. I worked harder on brushing and cleaning my teeth. After eight years, my dentist said my teeth were in good shape and clean. There was a tiny bit of tartar, so he advised me to see the dental hygienist anyway. The dental hygienist could have stopped after ten minutes, but she went on to arrive at twenty-five, so she could charge me for that, or so I thought. Probably, the treatment was always twenty-five minutes, regardless of the condition of the teeth. I found that dubious and looked for another dentist.

It would only get worse, even though not at the beginning. A new guideline stated that dental hygienists could do the periodic dental check-up. The following year, the dental hygienist combined the check-up with dental cleaning, making the most of the allotted time financially. I went there for thirty minutes. She billed me for thirty minutes of dental cleaning and also charged me for the check-up. A decent check-up lasts ten minutes, so you might expect a check-up and twenty minutes of dental cleaning if you are there for thirty minutes.

I was too surprised to protest. And I wasn’t sure. Had I checked the clock correctly? The following year, she did it again. Additionally, she charged me for taking X-rays and evaluating them. How can you do all that in thirty minutes if you already spend thirty minutes on dental cleaning? It doesn’t add up. The dentists had decided to take pictures every three years instead of five, which means more money for them. And she was double-charging me. Dental cleaning was € 160 per hour at the time, which was what I brought home after a day of work. Many people work longer for that money. To charge that per hour wasn’t enough for her, which is particularly nefarious.

After returning home, I emailed her to request clarification. She didn’t respond, so I filed a complaint with the Dutch Association of Dentists and looked for another dentist. In my complaint, I protested against the double charging and noted that questionable ethics appear customary in dental care. When I was young, there were no dental hygienists. My wife once said, ‘The dental hygienist is a new profession created out of thin air.’ She had left a dentist because he required her to see the dental hygienist without first examining her teeth to determine if that was necessary. I have heard stories from others of dentists overcharging or doing unnecessary treatments. And so, my suspicions, even though overdone perhaps, aren’t baseless.

My next dentist also advised dental cleaning. And this time, I was with the dental hygienist for forty minutes, and she billed me accordingly for € 119. Over the past fifteen years, the time spent on dental cleaning has increased by 300%, and the cost has risen by 467%. I take much better care of my teeth than I did twenty years ago and began using toothpicks, but it doesn’t show up in the dental cleaning cost. It can’t be that all these dentists and dental hygienists are lying. My teeth accumulate tartar no matter how well I clean them. I put up the ante once again, brushing my teeth three times a day, and it finally showed in reduced dental cleaning time in the years that followed.

The parabolic rise in dentist costs is mainly due to changing standards. Dental cleaning improves the health of teeth. My dentist now wants to take photographs every two years, whereas it was every five years a few decades ago. At some point, the benefits of increased cleaning and more photographs become minimal while the costs escalate. We have passed that point, but no one has put a halt to it. More and more people can’t afford dental care, and their teeth’s health suffers. General practitioners usually don’t benefit from the treatments they recommend, leading to very different professional ethics.

It demonstrates how a culture can emerge from circumstances and history. Dentists have a financial interest that promotes unnecessary treatments. Claiming a cavity is developing above a filling while there is not is outright lying. You have to be evil-minded to do that. But giving more treatments than necessary is a matter of debate. Dental cleaning and X-rays are suitable for opportunistic money-making schemes. The same trend is visible in veterinary practices. Douwe, our cat, suffered from kidney failure. We had spent hundreds of euros on tests, but the vets found nothing. We spent hundreds of euros more on special diets sold by these vets, but Douwe’s condition only deteriorated. Then we visited an old-fashioned vet who examined Douwe by feeling with his hand. He found the problem and euthanised Douwe. It cost € 30.

Modern veterinarians don’t physically inspect the animals but instead perform tests, charging over 1000% more. Physical examinations are bad for business. Vets make much more money from conducting tests. As a result, many pet owners can’t afford veterinary care, so either the animals suffer or their owners get into financial trouble. Today, there are expensive treatments that the wealthy can afford, like surgery. My father has spent over € 5,000 on surgery for the leg of his dog. An old-fashioned vet would have amputated the leg, as the animal could still walk on three legs. In hindsight, that might have been better because the surgery failed, so the dog had to undergo the procedure a second time. After that, the ailment returned, so a third surgery followed. My father had the dog euthanised because it was in pain.

You can’t blame only the vets and dentists for the cost explosion. Modern humans view their pets as family members rather than just pets and want the best for them, just as they do for their children. And they want perfect teeth rather than just healthy ones. Only, many people can’t afford it. Vets make tons of money. They now retire early, purchase luxury mansions and travel around the world. Vulture capitalists smell opportunity and are buying up veterinary practices. And so, it will only get worse. It shows that a group culture can be a problem. Most veterinary and dental care professionals think they are doing a good job and would object to outright fraud. The problem, however, is changing standards within their profession. It reflects the prevailing mood in society, where greed is now considered good. Most dental care professionals and vets are unaware of the damage their cultures and professional values cause.

The politically incorrect

It is okay to say that, but once you apply the reasoning to ethnicity, you step into a minefield. These differences can be an excuse for racism and discrimination. Racism is widespread, and discrimination is even more so. Typically, stereotypes are rooted in reality, which complicates the issue. Racism and bigotry are undesirable, but if you have reason to have grudges against specific groups, these grudges might express themselves as racism. You might as well hate Marlboro Red smokers and dentists. The standard politically correct answer is that most people from minorities are good people, just like most Marlboro Red smokers and dentists are. Additionally, the ethnic group to which you belong can also cause trouble for other groups. Whites caused the most trouble in history.

Usually, a minority in that group causes trouble, but that minority can make a neighbourhood unsafe. And people from a group don’t rat out each other, so that they can be part of the problem. There has been growing negativity surrounding immigration recently. That is not only because of the numbers, but also because of the crime. However, the image you get from the evidence you see is not reality itself. If most suspects of burglary have a particular skin colour, you might think they are all criminals, while it is usually a minority. Even when differences are relatively small, the groups in question pose a problem. If the percentage of criminals in the population rises from 1% to 2%, you need twice as many police, courts and prisons. And if you can’t discuss these issues, you also can’t discuss the problems the majority causes.

Usually, a minority in that group causes trouble, but that minority can make a neighbourhood unsafe. And people from a group don’t rat out each other, so that they can be part of the problem. There has been growing negativity surrounding immigration recently. That is not only because of the numbers, but also because of the crime. However, the image you get from the evidence you see is not reality itself. If most suspects of burglary have a particular skin colour, you might think they are all criminals, while it is usually a minority. Even when differences are relatively small, the groups in question pose a problem. If the percentage of criminals in the population rises from 1% to 2%, you need twice as many police, courts and prisons. And if you can’t discuss these issues, you also can’t discuss the problems the majority causes.

It works two ways. Host societies have varying ways of dealing with immigrants. The gang violence among immigrants is worse in Sweden than elsewhere. The Swedes tend to keep to themselves, and it isn’t always easy for foreigners to integrate into Swedish society. Many countries have volunteers who care for asylum seekers and help them settle. It is probably not a coincidence that my worst hitch-hiking experience as a youth occurred in Sweden, where my cousin and I waited for over seven hours for a lift despite the heavy traffic. Nowhere else had I waited for much more than an hour, and I have hitch-hiked in seven countries. Whatever the cause may be, these gangsters commit these crimes, not the Swedes who allowed them into their country. Still, there must be a reason why the gang violence in Sweden among immigrants is worse than elsewhere.

When harmful conduct relates to culture, the politically correct response is often that only a minority is involved in it. Why do mass shootings occur far more often in the United States than elsewhere? The politically correct gun lobby would argue that only a tiny fraction of Americans go on a shooting spree. The image you get is not reality itself. If there are mass shootings in the United States nearly every day, you might think Americans are gun-obsessed nutters, while it is a small minority. Still, there are mass shootings all the time, so it sets the United States apart from other countries. The problem is not gun ownership. Liberals might think that stricter gun laws will solve the problem. More stringent gun laws will never happen because the problem is not gun ownership but gun culture.

When there is no gun culture, gun ownership wouldn’t pose such a problem. European countries, such as Finland and Switzerland, also have widespread gun ownership. Still, random mass shootings are a typical American phenomenon. America has a gun culture and a belief that guns are a preferred way to solve problems. American police are over 60 times as lethal as their British counterparts (33 versus 0.5 fatalities per 10 million inhabitants in 2022), which is an appalling statistic. Still, several countries have far more violent police forces. These numbers relate not only to the amount of violent crime. Compared to films from other countries, American films overflow with excessive violence, including gory details like bullets penetrating bodies and tearing flesh apart, which Americans somehow seem to be particularly interested in. The hidden suggestion is that killing other people is business as usual.

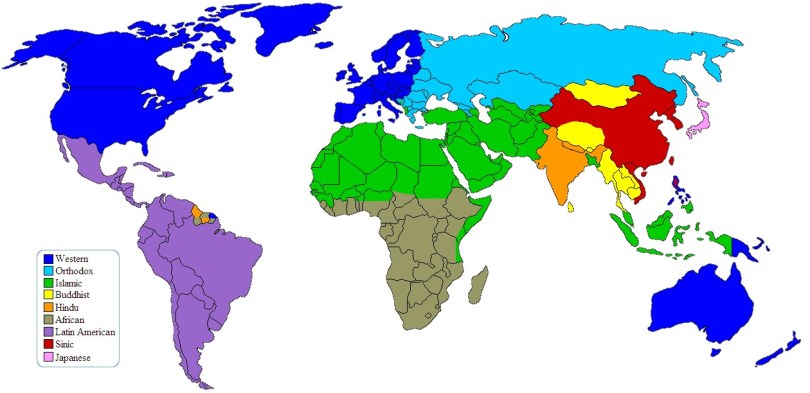

Ethnic groups have cultures. We picture Americans, Chinese, Germans and Arabs like we picture lawyers and construction workers. Our prejudices may accurately identify group characteristics, but will often fail us in individual cases. Suppose all the cookies are gone on Sesame Street, and you must find suspects. Would you not select the big-mouthed, blue-haired ones with a taste for cookies? That is also profiling. But perhaps it was one of Ernie’s pranks. If you did not think of that, you are prejudiced. We base our prejudices on experience and facts, as well as fiction and rumours. Only the facts do not base themselves on our prejudices. We often forget about that. Not all dentists are greedy money-grabbers, likely not even most. Although some minority groups cause more trouble than others, most individuals within these groups probably do well. Still, cultures and societies are Big Things, even though you can’t precisely define or measure them.

Intentions and arguments

In multicultural societies, people from certain ethnic groups often face greater difficulties and cause more problems than others. That undermines the fabric of society as much as racism and discrimination. It is one of the reasons why right-wing populism is on the rise. Culture often coincides with ethnicity, so the resentment can express itself as racism, which allows racists and bigots to have their say. That was the reason for having political correctness. Policymakers have long hoped that maintaining a friendly atmosphere and helping disadvantaged groups would help to reduce these problems over time.

The validity of an argument doesn’t depend on the intentions of the person making it. That said, there is a wide array of possibilities for misrepresenting the facts, so intent usually matters for the quality of the argument. Activists are cherry-picking incidents to present a picture of a group causing trouble. I could have photographed discarded, empty Marlboro Red cigarette packages on the street to illustrate that Marlboro Red smokers are littering jerks. Although there is some truth to it, it is not the truth itself.

Our cultures and values play a crucial role in how we view society. Groups that pose problems often share a belief that the society in which they live is not their own. ‘It is a white man’s world,’ a black man might say. You may become angry or frustrated when you fail in society due to circumstances you believe are outside your control. You may not understand the unwritten rules or know the right people to get ahead. Even when we are equal before the law, we are not in reality. It is not always easy to determine to what degree you can blame society, the individual, or the groups to which individuals belong.

Ethnic profiling

Cultural differences are why authorities engage in ethnic profiling. Culture coincides with ethnicity. In the Netherlands, crime rates vary by ethnic group. Criminals are a minority in every group, but the differences are significant. People of Antillian, Moroccan, Surinamese and Turkish descent are, on average, three times more likely (2.4%) to be crime suspects than native Dutch (0.8%). It has a magnifying effect, as it influences how the native Dutch think of these people. When you see pictures of crime suspects, they often have, as the Dutch call it, a tinted skin, meaning they aren’t white. It can give you the impression non-whites are all criminals, just like you can get the impression that all Americans are gun-wielding nutters or that Marlboro Red smokers are jerks. It can make you distrust people who aren’t white, most notably when you hardly know them.

The relationship between ethnicity and crime can be misleading. There is a coincidence between income and crime. And these minorities have relatively low incomes. A good question is why people from certain ethnic groups have low incomes. That relates to culture, but it is not the only explanation. Many immigrants came to Western Europe for low-paid jobs that required little education. Their parents had little education. Education was not a high priority for them, so their children often ended up with little education. Even when income explains crime rates better than culture, culture still plays a significant role in income, most notably through attitudes towards education and work. It is something we can’t ignore as specific types of conduct relate to particular groups.

Diversity policies, such as hiring persons from disadvantaged groups, can help improve society. However, the result can be that better-qualified people don’t get the job because of their skin colour or gender, which is discrimination. And, if you don’t hire the best people for the job, the quality of your product or service can come under pressure. On the other hand, without diversity policies, talent may go to waste. You can train talented people when they lack education. The Dutch government invested in the education of minorities rather than promoting diversity in hiring. Equalising opportunities with education seems a better approach than lowering standards.

Ethnic profiling is controversial. It has undesirable consequences, as the following example demonstrates. Suppose a country consists of two ethnic groups, which are Group A, 2/3 of the population, and Group B, 1/3. Assume further that people in Groups A and B are each responsible for 50% of Fraud X. Hence, people in Group B are twice as likely to commit Fraud X as people in Group A. To combat fraud effectively, you can only verify individuals from Group B to achieve the maximum result. You could apprehend twice as many fraudsters with the same effort. But now comes the catch. You don’t check on people from Group A, so only people from Group B end up in prison. While responsible for 50% of the fraud, Group B receives 100% of the punishment. That is discrimination.

Some call it racist, but the reason for ethnic profiling can be a risk assessment related to cultural characteristics, not ethnicity. In this hypothetical case, it is the likelihood of committing Fraud X. Also, in that case, ethnic profiling can be racist. People from Group A might dislike those from Group B and elect a leader who allows the authorities to investigate the crimes of Group B while disregarding the crimes of Group A. You can end up with a situation where the authorities prosecute Fraud X and only check on people in Group B, supposedly because they are doing it more frequently while doing nothing about Fraud Y, which members of Group A commit twice as often as those from Group B.

If your job is combating Fraud X, and you dedicate only 50% of your resources to Group B, that seems reasonable because people from Group B are responsible for 50% of Fraud X. In that case, people from Group B are still twice as likely to get punished because Group B is half the size of Group A, but receives the same amount of checking. And because people in Group B are twice as likely to commit Fraud X, people from Group B end up in prison four times as likely as those from Group A. While responsible for 50% of the fraud, Group B accounts for 67% of the prison population. If people from Group B claim that the authorities discriminate against them and punish them more, they are right.

People from ethnic minorities often get harsher punishment for the same crimes. A Dutch study showed that people from other ethnic groups are up to 30% more likely to receive a prison sentence for the same crime than native Dutch. The reason might be discrimination, but more likely, it is cultural. If you share the same culture with the judge, you know what to say to sway the judge’s opinion. Consequently, the judge might think the migrant is a jerk and the Dutchman is reasonable.

If the problem is severe enough, the end may justify the means. Ethnic profiling can undermine the trust of minorities in the authorities, because these groups may feel they are the target of police harassment. Still, if authorities don’t act on culturally related crime, we might end up with lawless ghettos. In several Western European multicultural societies, males of North African descent are overrepresented in the prison populations. In the United States, it is black males. On average, they commit more crimes than the general population. And if the police engage in ethnic profiling, people from these groups receive more punishment for the same crimes than others.

Ethnic profiling to check on people is one thing, but it becomes much worse when you use it to punish people without proof. The Netherlands has benefits with advance payments for medical expenses, rent and childcare. The tax service administers these benefits. These advance payments can bring people into trouble when it later turns out they aren’t qualified and must refund the money received. The rules were complex and prone to errors, as well as to fraud. Most irregularities occurred in areas where poor people lived, often ethnic minorities, so the tax service checked these individuals more closely. It remains unclear whether the tax service did ethnic profiling. Whether these were errors or fraud is often impossible to say, but he tax service didn’t need proof to label you as a fraudster and demand repayment.

Criteria can help identify potential fraud, but they don’t prove that someone committed fraud, nor can they distinguish between honest mistakes and intentional embezzlement. Suppose 5% of the people who used the childcare arrangement committed fraud. Assume also that there were criteria to select the 20% doing 80% of the embezzlement. In that case, 20% of that selection commits fraud, and 80% do not. There was a political climate that promoted harsh treatment of ethnic minorities. A decade later, thousands of people were in financial and emotional ruin. Complex regulations lead to errors and encourage fraud.

Officially, there is no ethnic profiling in the Netherlands, but it does happen. The Dutch government conducts an offensive against ‘undermining crime’ in selected poor neighbourhoods. In Zaandam East, it led to the surveillance of suspicious individuals and manhunts, sometimes based on hunches rather than evidence. The area is known for the window-cleaning gangs that divide up territories and use violence against the competition. It has been hard to crack down on these gangs, and Dutch authorities fear that criminals are undermining Dutch society. Zaandam East is one of the twenty areas targeted by the National Programme for Liveability and Safety, a drastic approach to ‘clean up’ city districts. The people living there are mostly foreigners, often from Bulgaria and Turkey. The methods the authorities use may not always be lawful, and critics ask whether the fraud and crimes committed by native Dutch receive similar scrutiny.1 Still, fighting organised crime requires intrusive methods. Zaandam-East is a crime-infested neighbourhood, but the majority of people living there aren’t criminals. I have known two Turks who lived in Zaandam. They were ordinary people with jobs.

Discrimination everywhere

Municipal officials from ethnic minorities experience discrimination and racism by colleagues, a 2023 survey in the Netherlands revealed. Civil servants participating in the survey reported facing discrimination, such as receiving criticism when another member of their ethnic group misbehaved. Those who spoke out against those remarks faced bullying and exclusion, so others kept their mouths shut out of fear of losing their job or being labelled a problematic case. Many municipal officials from ethnic minorities left their jobs due to racism and also because they had fewer chances of promotion, the report said.

Discrimination is not a trivial issue, but there are two sides. Those who make the remarks may think they are funny and that their jokes are harmless. They don’t think of the consequences. Bullying and exclusion can cause long-lasting trauma. Some complainers might have displayed unacceptable behaviour or taken offence at issues a Dutch person wouldn’t. We have no footage to establish what happened. In many cases, attributing the problem to discrimination based on ethnicity only scratches the surface. Bullying and exclusion happen for many reasons. It has to do with how humans behave in groups.

In workplaces, a pecking order often exists, with leaders, followers, and outcasts. Humans desire to establish social hierarchies. Some want to be the boss. To be a leader, you must demonstrate strength and confidence. A low-risk approach is attacking the weak or those who are different. There is also a group culture that defines how you should behave. Causing problems for the group and not fitting in are reasons for bullying. These issues may relate to skin colour, sexual preference or political views. Angry responses demonstrate your weakness. Reporting incidents makes you a rat.

Workplaces should be safe, but that is not always the case. In a properly functioning group, members respect each other, do not exploit each other’s weaknesses, and resolve their differences. For some reason, people can’t always get along. In a job environment, it can be performance on the job. I have worked in a Java team for over a decade. Due to our responsibilities, we couldn’t afford to have underperforming individuals on our team. There was no bullying, but three people had to leave the team because they weren’t performing adequately. These situations were unpleasant.

It is often difficult to pinpoint the exact reasons why people encounter difficulties at work. They may experience discrimination, but the underlying cause may be something else. What makes the outsiders different is usually the point of attack for the bully, making it appear to be a form of discrimination. Employers seek to select individuals who fit in with the team. They are in business to make money, not to settle disputes. Cultural differences can be a source of trouble, and discrimination is often subtle, as employers may have reasons to discriminate.

Once, I had a colleague from Suriname. He was a temporary hire who worked for a software agency. His uncle was his boss. He also came from Suriname. Out of the blue, he told me that he was the only Surinamese working for the agency. His uncle preferred Dutchmen because he could depend on them. They did as asked and kept their agreements. People from Suriname are more relaxed and often come up with excuses as to why they fail to meet their schedules, he seemed to imply by saying that. Customer satisfaction is key to business success, so it matters who you hire. His uncle was a businessman, not a philanthropist. It might have been better if he had hired a few more Surinamese and taught them to take their jobs more seriously and meet appointments. That would have been a diversity policy that could have helped to reduce the issue.

Minorities also discriminate. We are all human, after all. If people from an ethnic minority discriminate, it may seem less damaging than when the majority does it, as minorities usually have fewer favours to dispense. That is probably why liberals looked the other way. Jews are an exception. They have amassed so much wealth and power that their favouring of Jews has become extremely harmful. But few dare to speak out about Jews. Discrimination by minorities undermines society as much as discrimination by the majority. When I was on holiday in the United States, I once wanted to book a hotel room in a black neighbourhood in Miami. The lady behind the reception was kind enough to advise me not to. But if a white man can’t safely sleep in a hotel room in a black neighbourhood, how can blacks expect whites to stop discriminating against them?

One of the most disgraced minorities in the Netherlands is Moroccans because of the troubles caused by young males from this group. Many of them look down on compatriots who have done well in Dutch society. Had the mayor of Rotterdam, a Muslim of Moroccan descent, wished to run for Prime Minister, he would have stood a good chance. But on the message board for Moroccans I regularly visited, there were no words of praise. Several posters saw him as a defector. Also, the Moroccan lady who made it to the speaker of the house received few regards. They see themselves as ‘us’ and the Dutch as ‘them’. Discrimination works both ways. You will never become part of society if you think like that.

What is the matter with me?

I once asked myself the following question. Suppose I had room to let, and two men applied, one a white man from Bulgaria and the other a black man from Suriname. Both had similar jobs, and both gave a favourable impression. Who would get the room? Probably, I would choose the man for Suriname. Suriname has been a Dutch colony, and most people from Suriname living in the Netherlands are nearly as Dutch as the Dutch themselves. I have a prejudice that Surinamese are relaxed people who seldom cause trouble. About Bulgarians, I know far less, and I have never spoken to one. For the same reason, I would have selected a Dutchman if he had made a similar impression.

So, where did I get the idea from that Surinamese are okay? The people I have met? Television? It is unclear. Knowing I am biased, I would still choose the man from Suriname. Surinamese are culturally closer to the Dutch than Bulgarians, and I know more about them. And here we arrive at the heart of the matter, something overlooked in debates about racism and discrimination. About Bulgarians, I know very little. And Bulgarians differ more from native Dutch than Surinamese. When I rent out a room, I don’t want trouble. Judging native Dutch is hard enough already, let alone people from other cultures.

I discriminate and have prejudices like most people. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have opinions about liberals, conservatives, Muslims, Chinese, Germans, dentists and Marlboro Red smokers. I may not always be aware of my biases, but I am not s racist. Otherwise, I would have selected the white guy. It is better to diagnose my condition as xenophobia. I know more about Suriname and Surinamese. That is not to say there is no racism or that it is not widespread, but the underlying issues are often unfamiliarity and cultural differences. And so, identifying the issue as racism only scratches the surface. If you intend to solve the problem, that kind of simplicity doesn’t get you very far.

Those who are different face exclusion and violence. And I am different, so I know what it means that others pick you out for special treatment for no other reason than who I am. It makes you doubt yourself and ask, ‘What’s the matter with me?’ By the time I had become a student, I had become an emotional wreck, mired in self-doubt. But it is how groups of humans deal with deviant behaviour and press for conformity. Even people who think they are open-minded and cherish diversity do it because they don’t tolerate those who disagree. That is what Woke people do. Cooperating in groups requires conformism, so cultural differences and unfamiliarity cause trouble and uncertainty.

It begins with basic things, such as appointments. That made the Surinamese employer not hire his fellow Surinamese. I had a friend who was always late when we went out. He didn’t do that at work, of course. He married a lady from Africa. When she came with him, they were even later. Their marriage worked well because they shared a view on keeping schedules. It wouldn’t have worked with me. It might seem a minor issue, but a foundation of modern civilisation is maintaining schedules. In a business, it is a matter of survival due to competition. The solution, however, might not be for Africans and Surinamese to join the rat race but rather to end the system that drives us to destruction. That is why we must first identify what the future requires of us before we demand that people fit in.

The requirement of fitting in still allows for diversity in traditions as long as they don’t cause harm to nature or other people. Everything is interconnected, so not only do crimes like shoplifting and selling drugs do damage, but also, when there is no direct causal relationship between actions and consequences, such as dumping garbage or spreading hatred, and dying animals and terrorism. The same is true for discrimination. There may be good reasons to discriminate, but there can also be better reasons not to, or to help individuals from disadvantaged groups. Think of the benefits in the long run and the long-forgotten words of Martin Luther King,

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the colour of their skin but by the content of their character.

Today, King’s dream seems like a distant memory of the past. We are not there yet. It might testify to the stubbornness of the issue. The recent rise of fascism in the West, however, masks the progress beneath the surface. There may be a lack of willpower, but above all, there is a lack of self-criticism among all those involved, as existing traditions and cultures hinder progress. Perhaps it was too much in the 1960s. The colour of your skin can say something about your character, as there is a relationship between ethnicity and culture. Different cultures pose different problems. Throughout history, multiculturalism has been a tool employed by emperors to manage culturally diverse empires. And so it will be for the coming messiah if he is to unite the world. Multiculturalism is the proverbial One Ring and the road to closer integration. If God’s Paradise endures, cultures will lose significance, and the world will be one.

Latest revision: 18 July 2025

Featured image: Black and white sheep. Jesus Solana (2008). Wikimedia Commons.