Commercial versus savings banks

Historically, the banking sector comprised several types of banks. The distinction between commercial banks, which create money, and savings banks, which don’t, has lost its value due to the existence of efficient financial markets, where banks match terms through borrowing and lending. The distinction between created money and savings is arbitrary, as the following example demonstrates. Suppose that I work at a farm, and the farmer rewards me with a plot of land and leftover wood and materials from a defunct shed, which I use to build my home. After finishing my house, I go to the bank and take out a mortgage. The bank creates money out of thin air.

Until I went to the bank, no money had changed hands. Still, I was able to save for a home of my own. In other words, savings aren’t the same as money in a savings account. In this case, my savings are my home, and if the mortgage is a debt, the money I take out is my savings. To further illustrate the point, suppose that I have no money and also own no home. When I go to the bank for a car loan, the bank creates this money on the spot. If you think there are no savings, you are wrong again. The person who sold you the car had saved the car. I can even borrow money and put it in a savings account. And so, I created savings from thin air by borrowing money and lending it to the bank.

Full-reserve banking

A well-known monetary reform proposal is full reserve banking, as outlined in the Chicago Plan, which means there are only savings banks and no commercial banks that create money. It often resurfaces when banks go bankrupt. With full reserve banking, banks can’t lend out funds deposited in demand accounts or current accounts. Money in these accounts isn’t debt but backed by central bank currency or cash. And depositors can’t withdraw the money from their savings accounts on short notice. In this way, banks can’t go bankrupt because of depositors demanding payment in cash. With full reserve banking, loans must come from savings, which are funds that depositors can’t withdraw on demand, as they have entrusted them to the bank for an extended period.

Lack of cash is usually not the primary reason banks fail, but rather, loan write-offs. That was also the case during the 2008 financial crisis. Full reserve banking addresses a liquidity problem, whereas the crisis was a solvency issue that subsequently led to a liquidity issue. Banks ran into trouble, not because they lacked cash, but because they incurred losses on their loans. As a result, banks began to distrust one another and stopped lending to each other. The financial system can be safe with zero reserve banking, provided that banks are solvent, thus have sufficient capital, and own adequate liquid assets, such as government bonds, that they can sell to meet withdrawals. And so, a reserve requirement can better include liquid safe assets, such as government bonds, rather than currency alone.

Some proponents of full reserve banking are socialists who oppose privately controlled money creation, as they view it as a public subsidy to the private banking sector. Others desire a banking sector free from government interference, so a ‘free’ banking market without central bank interventions and deposit guarantees. At least that is something socialists and their opponents might agree on. Bank credit can contribute to economic cycles and financial crises. With full reserve banking, there would be less bank credit, and interest rates would be higher. To make lending possible, depositors must part with their money for a designated period of time to make it available for lending. As a result, fewer funds are available for lending, and interest rates would be higher.

Shadow banks

Full-reserve banking makes financial markets less efficient, allowing alternative schemes, such as shadow banks, to fill the gap. An example can illustrate that. Suppose that God has ordered banks only to use money in savings accounts for lending so that there is full reserve banking in Paradise. Eve and Adam only do business with each other. Both have €100 in their current account, which they use for their daily business transactions. This money is suitable for payment because it is in the current account. For that reason, they don’t receive interest. Assume now that the bank also offers savings accounts with an interest rate of 4% but money in savings accounts isn’t suitable for payment.

Then a financial advisor comes along, disguised as a snake, advising Eve and Adam for a reasonable fee on how to manage their payments between themselves and to deposit their money into a savings account. So, what you now read in Genesis is made up by bankers to hide their fraud, a conspiracy theorist might infer. But it is just a story. In this way, Eve and Adam both earn interest on their €100. They give each other credit, so that Eve can borrow €100 from Adam, and Adam can borrow €100 from Eve. They don’t need to keep money in their current accounts, so they deposit their funds into a savings account and earn interest. Everybody wins, Eve, Adam, and of course, that snakelike creature.

Initially, Eve and Adam had no savings, only money in their current accounts. The advisor’s scheme allows them to fabricate savings out of credit. It seems like creating money, but Eve and Adam gave each other credit. They agreed to pay later, which exposed both to credit risk. One of them might not repay because you can do so many different things with €100 than put it in a savings account. You can use credit, which is an agreement to pay later, and use it like money. And so, Paradise was lost. Similar schemes exist on a larger scale. These are shadow banks. Shadow banks don’t create money but credit. The difference between fractional reserve money and this type of credit may not be significant in practice, except that it is unregulated, resulting in little oversight.

When banks create money, they do the same. The banks act as intermediaries between Eve and Adam, allowing them to lend money to each other even when they do not conduct business with each other or do not trust each other. The bank also assumes the risk that a debtor will fail to repay and receives a reward in the form of interest. It is also credit, but we refer to it as money because the law regards bank credit as legal tender, thus money. The government backs this scheme, as a stable financial system is a key public interest. Banks must have sufficient capital and reserves to meet emergencies. For that reason, banks are subject to regulations, while shadow banks are not subject to these rules, allowing the latter to offer more competitive interest rates.

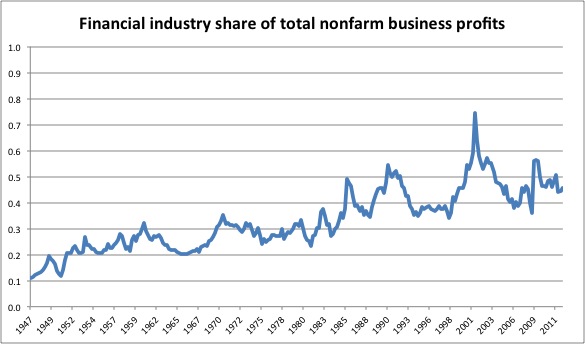

As a result, the role of traditional banking has declined. Large corporations could lend and borrow in money markets at rates better than those offered by banks. At the same time, retail investors could invest directly in money markets and get better yields than banks offer. This development started with corporate borrowing. It later expanded into mortgages. The primary reason for regulating banks is that they operate the payment system, which is of public interest, and can borrow from the Federal Reserve. It prompted banks to strip their balance sheets and expose themselves to off-balance sheet risks to generate higher returns on their capital. For instance, offering an emergency credit line to a shadow bank generated profits while not appearing on the balance sheet.

The 2008 financial crisis originated in shadow banks that invested in risky assets, rather than conventional banks that create money through lending. Shadow banks aren’t subject to the same regulations as traditional banks, so they made speculative investments in mortgages. These investments appeared safe because rating agencies failed to do their jobs. Regular banks encountered trouble because they had backed shadow banks, hoping to reap a quick profit from credit insurance. The word they use is off-balance sheet financing. The regular bank didn’t lend money, but guaranteed credit to shadow banks in case of emergency, which is as dangerous as keeping the mortgages on its own balance sheet. But that was legal. It allowed banks to make more money from the same capital. Money creation, therefore, wasn’t the problem, and replacing regular banks with shadow banks could further destabilise the financial system.

If a financial crisis were to occur with loan write-offs, full reserve banking would only ensure that money in current accounts is safe. However, the same problems would emerge in savings accounts. Savings banks can expose themselves to off-balance sheet risks, unless that is forbidden. And they can also go belly up. And they did. If the debtors of a bank fail to meet their obligations, the bank may face financial difficulties, and the savings it holds may be at risk. Also, with full reserve banking, governments and central banks may end up supporting savings banks and even shadow banks to ensure financial stability, thereby rendering the benefits of full reserve banking void. After all, the initial cause was never a liquidity problem, but a solvency issue.

Commercial versus investment banks

The Glass-Steagall Act in the United States severed linkages between regular banking and investment activities that contributed to the 1929 stock market crash and the ensuing depression. Separating banking from investing can prevent banks from providing loans to corporations in which they have invested. The measure aimed to make bankers more prudent. The separation of commercial and investment banking prevented securities firms and investment banks from taking deposits. The reason for the separation was the conflict of interest that arose from banks investing in securities with their own assets, which were their account holders’ deposits. Banks were obliged to protect the account holder’s deposits and should not engage in speculative activities.

The Glass-Steagall Act included the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), which guaranteed bank deposits up to a specified limit. It also comprised Regulation Q, which prohibited banks from paying interest on demand deposits and capped interest rates on other deposit products. Maximising interest rates can limit the risks banks are willing to take on loans, as these risks can destabilise the financial system.

Until the 1980s, the legislation mainly remained unchanged. With the rise of neoliberalism, government regulations became increasingly disapproved of. Hence, the Glass-Steagall Act became increasingly disregarded, and diligent deregulators repealed it in 1999 as part of their effort to relieve businesses of government regulations that stood in the way of corporations making profits at the expense of the public good. Regulation Q ceilings for all account types, except demand deposits, were phased out during the 1980s. After the 2008 financial crisis, a renewed interest in the Glass-Steagall Act emerged.

In the United States, money market funds circumvented the limits imposed on banks by Regulation Q, luring depositors with higher interest rates, thereby undermining the prudent banking paradigm. The money market funds, which are shadow banks, invested in collateralised debt obligations (CDOs), such as mortgage-backed securities (MBS). The 2008 financial crisis started in money market funds, not traditional banks.

Natural Money works with the same principles. It distinguishes between regular banks, which provide loans, and investment banks, which are partnerships that invest in equity. Islamic banks also operate similarly. The maximum interest rate of zero works like Regulation Q, aiming to limit the risks banks are willing to take on deposits, as interest is a reward for taking on risk. Banking in a Natural Money financial system works as follows:

- Regular banks make low-risk loans. The money in these banks is secure. The maximum interest rate is zero. And so, deposits have negative yields.

- Investment banks don’t lend but participate in businesses by providing equity. They can rent houses and lease cars. Investment banks offer higher returns.

- Both regular banks and investment banks can invest in government securities to manage their risk and meet withdrawals.

- Regular banks can promise a fixed interest rate. The government may offer support and deposit guarantees.

- Investment banks don’t guarantee returns. They pay dividends based on their profits. Its depositors are investors who can face losses.

Natural Money enhances financial stability by favouring equity investments over debt investments. The maximum interest rate makes debt investments less attractive. And there is no reward in the form of interest for engaging in high-risk lending, which enhances the financial system’s stability. It stands to reason that the integrity of the system depends on strict adherence to its principles and the termination of evasive, get-rich-quick schemes of financial parasites, which requires a belief in the vision behind the idea of a usury-free economy. Let’s not dismiss that as a fantasy immediately.

Sanitation of banking

The primary cause of the financial system’s failure is usury. Imagine what a maximum interest rate of zero on debts can do. Only the most creditworthy borrowers can get a loan. You may have to save and bring in equity before applying for a mortgage, and that may be the only credit you can obtain. Even an overdraft may be impossible. That may seem harsh, but it is even worse when indebted consumers reach the point of interest payments and can’t make ends meet. If you want to buy something, you have to save for it. Likewise, corporations need to attract capital rather than debt to meet their liquidity requirements. The financial sector will shrink, and much of modern finance may become redundant.

That said, individuals and businesses may obtain better deals in the money market, allowing them to opt for this option rather than a bank. The distinction between traditional banks and shadow banks may blur. Tradional banks may need fewer regulations while shadow banks may need more. That is because without interest, risk may disappear. The central bank may stand behind the payment system, but it may not have to stand behind the lending system. The implicit guarantee of central banks buying debt and issuing currency with a holding fee means that the warranty will remain unused.

Two other themes emerged during the 2008 financial crisis: ‘too big to fail’ and ‘too complex to understand.’ Complexity and size are the outcome of competition. The failure of a large bank can bring down the financial system, and the products traders in financial markets use to hedge their risks or improve their profitability can be complex. Our future civilisation could be simpler, so the sanitation of the financial system should encompass cooperation, simplification and diversification. It may look as follows:

- There should be an exhaustive list of all legal financial products and their requirements. We shouldn’t allow other financial products to exist.

- No bank should hold more than a certain percentage of the global market, and no bank should expose itself to more than a certain percentage of another bank.

- Banks should share services where scale is crucial, such as technological infrastructure and advanced knowledge.

Smaller banks can achieve efficiency improvements by using the same technological infrastructure. As long as they are independent financial institutions, they may share an IT department and operate their businesses on the same software. It may even be a public infrastructure that all banks share, allowing for significant cost savings, while also sharing knowledge and implementing measures related to issues such as fraud prevention.

Latest revision: 13 November 2025

Featured image: Ara Economicus. Beverly Lussier (2004). Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.