Setting interest rates

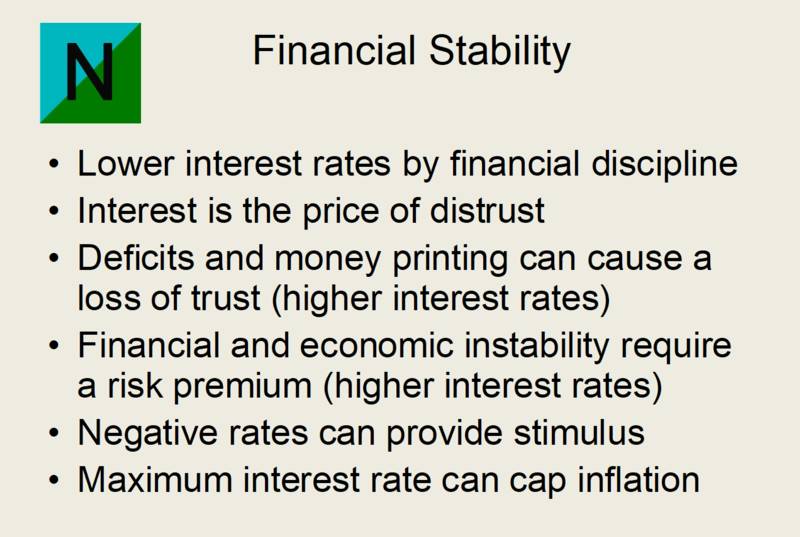

In the current financial system, central banks manage the money supply via interest rates. When the central bank lowers interest rates, borrowing money becomes cheaper, making it more attractive to go into debt for consumption or investment. As a result, the money supply increases at a faster pace, which then boosts consumption and investment. When the central bank raises interest rates, the opposite happens, and the money supply increases at a slower pace, or even decreases.

Central banks boost the money supply because usury promotes a money shortage. Most money is a debt, on which debtors pay interest. Debtors must return more than they borrowed. That money may not be available if those with surpluses don’t spend their balances, requiring more borrowing to prevent a disruption in the money flows. Classical economics questions this idea. If the money flows become interrupted, sellers lower their prices, and those with money will spend more to pick up these bargains.

Transmission via the bond markets

Based on estimates of future short-term central bank interest rates, financial institutions such as banks borrow short-term money from the central bank at the interest rate set by the central bank to buy longer-term government bonds. If banks expect the short-term interest rate to remain below 2% in the coming year and 1-year government bonds yield 3%, they may borrow short-term money from the central bank to buy these bonds, repay them when they mature, and pocket the 1% difference.

The trade creates demand for these bonds, causing their price to rise and their yield to drop. Perhaps traders stop buying the bond when the interest rate drops to 2.5% because there is always a risk that the central bank will raise interest rates during that year. If 10-year bonds yield 4%, another trader might sell 1-year bonds and invest the proceeds in 10-year bonds, thereby lowering their yield as well. Usually, this happens in future markets, so traders often don’t own these bonds.

Altering markets

Central bank critics argue that they distort markets by eliminating the market mechanism. Central bank interventions have a profound impact on the operation of financial markets. As a result, there is more lending than would have occurred otherwise. Central banks create liquidity in financial markets by providing short-term funds that banks use to buy bonds with different maturities. It allows banks to buy and sell these government bonds, enabling them to match their lending and borrowing needs at any time.

So, how does that work? Apart from lending to customers, banks invest in government bonds, which they can sell at any time, as they can trade government bonds in financial markets. If a corporation requests a one-million-euro loan that matures in five years, the bank might sell a five-year government bond. In that case, the bank eliminates the interest risk, as it knows the amount of interest it would have received by keeping the bond and the interest it will receive from the loan.

In the past, banks had to be careful because they couldn’t borrow easily from the central bank, nor did they invest in or trade government bonds. So, if you applied for a mortgage, the bank looked for matching term deposits. Perhaps you could obtain a 5-year mortgage if there were sufficient 5-year deposits available. If, after five years, the bank lacked adequate deposits, you would not be able to renew your mortgage and might have to sell your home. And so, you would think twice before getting a mortgage.

Economists call these markets inefficient. You couldn’t get a 30-year mortgage. The operation of central banks has altered financial markets, making them more efficient. That can be beneficial for the economy. The Industrial Revolution started in England. England had the most efficient financial markets. The central bank needs the trust of financial markets. Financial markets can lose confidence, which can lead to a decline in the currency’s value. A central bank can try to restore trust by raising interest rates.

Subsidising the financial sector

Central banks reduce the risk of bank failures. When borrowers repay their debts, banks are solvent. However, they may find themselves short of cash in their vaults when depositors withdraw their deposits. Central banks create this money if needed, so banks need less cash in their vaults. Central banks can also rescue banks in trouble, thereby reducing the risk to the broader economy. After all, a financial crisis can lead to an economic crisis, such as the Great Depression. That nearly happened in 2008.

There are public benefits to stabilising the financial system, but these benefits exist due to interest on money and debts, thus usury. Usury creates a shortage of funds that requires management. Central banks subsidise the financial sector in the following ways:

- Central banks mitigate the risk of systemic failure, enabling financial institutions to take on more risk and lend more. Banks may make risky loans to profit from higher interest rates, assuming the central bank will bail them out if things go wrong.

- Central banks signal their intentions to financial markets. When the central bank intends to change interest rates, it provides advance notice so financial institutions aren’t caught off guard and can adjust their bond portfolios accordingly.

The supply and demand of funds in the financial markets ultimately determine interest rates. Still, these markets would operate differently without central banks, with significantly less borrowing and lending. Central banks make the financial system function more smoothly and reduce the risk of systemic failure. As a result, interest rates are lower than they would have been otherwise.

Central banks are powerful, undemocratic, technocratic institutions. Since the 1970s, they have become independent from governments. Before that time, governments used their central banks to finance their deficits through money printing, leading to inflation and a loss of trust in currencies. Making the central bank independent from politicians and giving it a mandate to keep inflation low was a move to instil confidence in fiat currencies.

The argument in favour of central bank independence is that a government must be trustworthy to its creditors. Creditors, like most of us, don’t trust politicians because they spend other people’s money. Since then, governments have borrowed in financial markets and paid interest on their debts. Central banks still buy government debt and return the interest to the government, which is the same as printing money outright.

Central banks can impede the functioning of financial markets by mispricing risk. Central banks can save banks in trouble by printing money. Without central banks, financial institutions would have to be more careful. Bank failures would occur more often, and banks would pay more interest to depositors to compensate for that risk. That negatively impacts economic growth and leads to crises. That is why central banks exist.

Signalling intentions

Central banks signal their intentions in advance to prevent traders from being caught off guard, thereby avoiding chaos in financial markets. That issue became at the centre of a drama that played out in the UK bond markets in September 2022. Interest rates spiked after the government announced a massive spending package. It suddenly became clear that the Bank of England might have to raise interest rates much further than previously thought to contain inflation. The spending plan caught financial institutions off guard. The Bank of England had to intervene in the bond market to bring down interest rates.

Financial institutions borrow short-term money from the central bank and invest it in the bond market. To borrow this money, financial institutions pledge these bonds as collateral, just like your house is the collateral for your mortgage. If interest rates rise, the value of these bonds decreases due to discounting the interest. A UK bond trader noted, ‘If there was no intervention today, yields on UK government bonds could have gone up to 7-8 per cent from 4.5 this morning, and in that situation, around 90 per cent of UK pension funds would have run out of collateral. They would have been wiped out.’

An institution might bring in £1,000,000 in equity to borrow £9,000,000 from the Bank of England at an interest rate of 1.75% and invest £10,000,000 in ten-year bonds at 3% interest, pledging the bonds as collateral for the loan. The institution could earn £142,500 per year on a £1,000,000 investment, yielding a handsome 14.25% return if market conditions remain stable. But it is a dangerous bet due to discounting. The price of a bond is its net present value. If the yield on ten-year bonds were suddenly to rise from 3 to 4%, the institution would incur a loss of £811,090, which is the difference in net present value of the bond. That would nearly wipe out the entire equity. And that happened that day.

In the past, pension funds invested in bonds for the long term, but bond yields were low. Pension funds have fixed obligations, such as paying a retiree €1,000 per month until they die. If interest rates are low, you have to pay more in pension premiums to arrive at that amount. To pump up their revenues, pension funds invested in stocks and speculated in the bond market using leverage. It seemed like easy money because central banks signal their intentions in advance. This time, however, the government took the traders by surprise, so the central bank had to rescue them.

Permanent liquidity

When there is liquidity in financial markets, you can buy or sell financial instruments like stocks and bonds at any time. In other words, you can sell them in the financial markets for currencies like the euro or the US dollar. During a financial crisis, liquidity becomes scarce, and it becomes harder to sell financial instruments. Their price collapses because there are many sellers and few buyers. Only cash and government bonds perform well in those times. Financial pundits refer to it as a flight into safety. To prevent a crisis, central banks inject liquidity into the financial system. In other words, they lower interest rates, making it attractive for investors to borrow from the central bank.

In this way, the central bank prints new money. It can end the crisis because investors can use this new cash to buy stocks. Since the 1987 stock market crash, central banks have increasingly resorted to adding liquidity or printing money to quell financial crises. If currency is plentiful, short-term interest rates drop, and stocks and bonds become more attractive investments, so there will be buyers. Once interest rates are near zero, the central bank can’t lower them; market participants may accumulate central bank currency rather than invest in stocks because they find an interest rate of zero more attractive.

In such a situation, investors will not invest but instead hold onto their cash. With interest rates near zero, traditional methods for addressing financial crises have become ineffective. That is why central banks adopted extraordinary measures, such as quantitative easing (QE), in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and the 2012 euro crisis. Investors say, ‘Cash is king.’ It is the ultimate means of payment. If your bank goes bankrupt, your deposit might be gone. But you can still pay with banknotes, which are the central bank’s currency.

During a financial crisis, people worry about whether their stocks will retain value in the future, as the economy may collapse. That is why investors also prefer central bank currency. But that is only due to the interest rate on cash. If there had been a 12% annual holding fee on central bank currency and cash, investors would seek alternatives to cash and central bank currency, and the market would always maintain liquidity, so that the central bank doesn’t have to take action. In that case, we may not need a central bank, and central bank currency becomes a unit of account or administrative currency.

In times of crisis, investors often rush to buy safe financial instruments, such as government bonds. With Natural Money, administrative currency is unattractive because of the holding fee. Holding on to the currency will cost you 12% per year, which means that a euro will be worth 88 cents after a year. And so, interest rates on government debt may be as low as needed, such as -5%, to make other investments more attractive and bring liquidity back into the markets. And so, there will always be liquidity.

No one wants to own currency that costs 12% per year to hold. It will mark the end of the administrative currency’s role as a reserve. Currently, banks are required to keep the central bank’s currency to meet their reserve requirements. That is unnecessary. Equity requirements are more helpful than currency reserve requirements. Government debt can also serve as a suitable reserve. Currently, banknotes are also the central bank’s currency. A 12% holding fee would make cash unattractive to use. Cash should have a backing of short-term government debt with a more favourable interest rate.

Latest revision: 13 November 2025

Featured image: Ara Economicus. Beverly Lussier (2004). Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.