We, humans, have become the dominant species on Earth. That is because we collaborate flexibly in large numbers. Social animals, such as monkeys and dolphins, work together flexibly but only in small groups. Ants and bees cooperate in large numbers but only in fixed ways. Language enables our large-scale, flexible collaboration. Some animals use signs and calls or give each other names, but we use far more words.1 That allows us to cooperate in more ways and for a wide range of purposes. Language allows us to make and communicate agreements. And we can describe things in detail. We can write, ‘Please read these safety instructions carefully before using model T92.’ Then follow many pages of instructions. Butterflies don’t observe a written list of safety instructions before leaving their cocoons like NASA does when launching a spacecraft. That is why butterflies have never landed on the Moon.

We are also imaginative creatures. We imagine things into existence. We envision laws, money, property, corporations, social classes and states. We imagine that there is a law, and that is how the law works. In other words, we envision the law, and lo and behold, it exists. The same is true for money and corporations. We humans say, ‘Let there be corporations.’ And lo and behold, there are corporations. Only humans do that. No other species envisions money and corporations. I can’t give a dog a debit card to go to the supermarket to buy dog food. A dog lacks the imagination for that. A dog can’t think of money, laws and corporations. And so, you can’t make dogs work together in a corporation to produce dog food by paying them money. Our fancifulness existed long before civilisations emerged. Archaeologists uncovered a 32,000-year-old sculpture of a lion’s head upon a human body. These lion-men only existed in the imagination of humans.

We are also religious creatures. We cooperate using myths. People of the same religion can go on a holy war together. Faith can also motivate people to engage in charitable work and provide for the poor. Religions promote social stability by justifying the social order and promising rewards in the afterlife for those who support it. As societies grew more stratified, the elites, such as kings and priests, tried to justify their existence and lavish lifestyles, and why peasants had to toil. And so, creation myths emerged, explaining that the gods created humans to work the ground. Established religions were often schemes to exploit peasants. You can’t let a dog submit to you by saying obedient hounds will go to heaven and enjoy everlasting bliss after they die, and unruly canines will be fried forever in a tormenting fire. A dog lacks the imagination to even think of it, let alone believe it. We have a religious nature. We make up stories and believe in them. We are social beings and need a group to survive. Beliefs hold groups of humans together, so it is a matter of survival to believe in our own imagination

Small bands of people cooperate because their members know each other and see what everyone contributes. In larger groups, that becomes more difficult as people can cheat. That is where states, money, and religions come in. They facilitate collaboration between strangers, allowing us to operate on a larger scale. States do so by coercion, money by trade, and faith by inspiration. As there has always been a survival-of-the-fittest-like competition between societies, those who cooperated most effectively survived and subjugated others. Religions forge bonds and help maintain peace within a group, or inspire group members to go to war. Religions played a crucial role in the survival of humans. If believing means surviving, it is rational to have faith, regardless of how curious the belief may be. It is in our nature to be religious, and usefulness rather than correctness is the essence of religion. And so, it is better to view a religion not as a set of lies, but as something people agree on to believe in, which helps them to cooperate and survive.

We make up stories and believe them. Hollywood films featured reptiles disguised as humans. Since then, some people have claimed that reptiles live among us disguised as humans. You can see how we can go collectively crazy in this way. When we retell stories, they change. We forget parts of a tale, add new elements or alter their meaning. And so beliefs and religions evolve. The evolution of religions has been a process in which ideas emerged and interacted. Early humans were hunter-gatherers who believed that places, animals, and plants possessed awareness, feelings, and emotions. They asked them for favours, like ‘Please, river, give me some fish.’ Hunter-gatherers felt they were more or less on an equal footing with the plants and animals around them.1 Animism is the name for these beliefs. These beliefs were local and concerned visible objects like a tree or a mountain. Over time, people began to imagine invisible entities like fairies and spirits. A crucial step in the development of religions was ancestor veneration.

The first humans lived in small bands based on family ties. Their ancestors bound them together. And so, they began to venerate the dead. It was a small step to imagine that the spirits of the dead are still with us and that our actions require the approval of our late ancestors. Ancestor veneration made it possible to envision a larger-scale relatedness in the form of tribes. A tribe is much larger than a band. The belief that its members share common ancestors holds a tribe together. Tribes are too large to identify their common ancestors, so tribespeople imagined their ancestors, and the stories about them are myths. The Romans started as a tribe. They had a myth about their founders, Romulus and Remus. As the tale goes, a she-wolf raised them. Tribes are much larger and can muster more men for war. That is why tribes replaced bands. It helps when people attribute magical powers to their ancestors and fear the consequences of angering them. In this way, ancestor veneration turned into the worship of gods. The previous beliefs didn’t disappear completely. Many people still believe in ghosts.

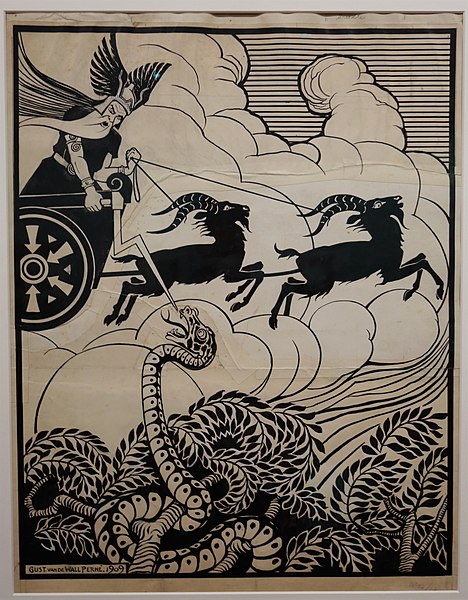

Hunter-gatherers can move on in the event of conflict, but farmers invest heavily in their fields, crops, and livestock. Losing their land, animals, or harvest meant starvation. With the arrival of agriculture, property and territorial defence became paramount. States defend their territory and can afford larger militaries. Kinship is an obstacle as states enlist the people within their realm, regardless of family ties. States thus needed a new source of authority, and the worship of gods replaced ancestor veneration. When humans subjugated plants and animals for their use, they needed to justify this new arrangement. Myths emerged in which the gods created this world and ordained that humans rule the plants and animals. In Genesis, God says, ‘Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground.’ (Genesis 1:28) Most of the world’s major religions originated in agricultural societies.

Religions emerged from ancestor worship. And so, gods could be like mothers and fathers. People gave devotion to several ancestors. Each ancestor had a specific admirable quality. Consequently, early religions featured multiple gods and goddesses, each with a distinct role. That is called polytheism, which is the belief in several gods. Henotheist religions emerged later when people became emotionally attached to one particular deity. Henotheism is the belief that multiple gods exist, but that we should worship only one of them. Even polytheists can believe there is a supreme being or principle. However, that supreme being is indifferent to our concerns, so it doesn’t make sense to direct prayers to it in the hope of receiving help. The gods, being on a lower level, have desires, so we can befriend them by making offerings, polytheists believed.1

The next step is monotheism, or believing there is only one God. Monotheists believe that there is only one God who rules the universe. Monotheistic religions were successful because monotheists, most notably Christians and Muslims, have missionary zeal. They believe that God craves our worship. Converting others is an act of mercy, as unbelievers will end up in hell. The worship of other deities is an offence to monotheists. After all, it contradicts their belief that there is only one God worthy of infinite adoration. Failing to take action against the unbelievers could anger God. Polytheists are less likely to feel offended when some choose to worship just one of the many deities or invent a new one.

In the first centuries AD, Christianity replaced the worship of local deities. To help pagans accept Christianity, the Church replaced these deities with saints, who often had the same purpose, and took over existing holidays. Each saint had specific qualities, just like the previous deity. In Ireland, St. Brigid of Kildare replaced a Celtic goddess with the same name. Both occupy themselves with healing, poetry, and smithcraft, and their feast day, 1 February, is the same, which is not a coincidence. And so, polytheism didn’t disappear entirely, as Christians continued to pray to saints. The Church also took over the Roman holiday commemorating the winter solstice, which was on 25 December. It turned pagan rites to celebrate the rebirth of the Sun into a Christian feast commemorating the birth of Christ.

Monotheism comes with a few logical difficulties. We hope that God cares for us and answers our prayers. However, prayers are often not answered, and bad things are happening. So, how can an almighty Creator allow this to happen? The obvious answer is that there is no god, or God doesn’t care. That is not what we want to hear. And so people imagined Satan, God’s evil adversary, who makes all these bad things happen.1 And we hope that the people we hate receive punishment, if not now, then in the afterlife or a final reckoning on Judgement Day. Religions cater for our sentiments, a psychologist might say.

In modern times, Europeans developed ideologies, such as liberalism, socialism, and fascism, which, like moral philosophies, describe how we should live. These ideologies are much like religions. They have prophets, holy books, missionary zeal, and preachers. The prophets of communism were Marx and Lenin. They had theologians who explained their writings. The communists had public holidays, such as 1 May, and heresies like Trotskyism. The Soviet army units had chaplains to oversee the faithfulness of the troops, although the Soviets named them as people’s commissars. The communists further expected an end time, the proletarian revolution, after which they would enter Paradise, world communism. A fanatic missionary zeal further characterised Soviet communism.1 And so, communism is much like a religion. The foundations of the ideologies of liberalism and socialism are the Christian values of freedom and equality. Fascism developed from nationalism, and the struggle for survival in nature inspired Nazism, which helped to make it especially cruel.

After the Middle Ages, educated Europeans began to doubt Christianity. The contradictions in the Scriptures began to attract attention. And then came the party pooper, Charles Darwin, who wrote On The Origin Of Species. Plant and animal species are the outcome of a struggle for survival. Despite the frantic efforts of religious people to fiddle with the facts, the evidence continued to mount. Religions exist because we invent stories to promote cooperation, and that contributes to our success, not because there is an invisible fellow in the sky. But human imagination reigns supreme. We live in such a universe created by an advanced humanoid civilisation. That already happened. We live in such a universe. And so there is a God after all.

Latest revision: 23 September 2025

Featured image: Lion-headed figurine from Stadel in the Hohlenstein cave in Germany. J. Duckeck (2011). Wikimedia Commons.

1. A Brief History Of Humankind. Yuval Noah Harari (2014). Harvil Secker.