Negative electricity prices

Solar is the cheapest source of energy, but only when it is available. When the Sun doesn’t shine, there is nothing. And there can be more than needed. Electricity prices in the Netherlands go below zero for most of the day during sunny and windy summer weekends. When solar panels and windmills produce the most, it costs their owners money to bring that power to the grid. In 2023, electricity prices reached a negative € 0.40 per kilowatt-hour on a few occasions. Taxes and delivery costs were € 0,15, so people with a dynamic energy contract could make money using electricity in those instances. As one energy expert put it, ‘This is nuts.’1 Since then, shutting down solar and wind farms during peak hours has helped keep prices in check.

The Netherlands has a massive solar and wind capacity, often-changing weather, a lack of battery storage, and a stressed power grid. In 2022, 40% of the Netherlands’ electricity and 15% of its total energy consumption came from renewable sources. It could be just the beginning if the Netherlands intends to become climate-neutral. There are plans for more wind and solar farms. To manage all that, you need large batteries and hydrogen to store electric energy, as well as more nuclear power plants or plants that run on fossil fuels to bridge periods with little sun and wind. It will be costly, which is why investors have second thoughts. The Dutch might be better off becoming climate neutral by curbing their energy use. Only that would be a capital sin in our religion of economic growth.

In the drive to reduce carbon emissions, households are increasingly electrifying their energy consumption, using electric heating and electric cars, resulting in higher electricity demand in the winter and further stress on the grid. There is only so much shifting of energy demand that flexible pricing can achieve. Power outages during peak hours become increasingly likely. Further down the road, the Dutch might end up shutting down energy-intensive industries in times of a lack of renewable energy. Did no one see that coming? Policymakers have ignored this massive problem. In any case, the costs of halting climate change will be staggering, so some say renewable energy is a religion.

Critics had a field day in 2023 when the Dutch Climate Minister said that the proposed measures to combat climate change would cost € 28 billion over seven years, or € 222 per person per year, and reduce global temperatures by only 0.00036 degrees Celsius. ‘This is nuts,’ they said. No one will notice the difference. And in 2025, a new figure emerged to shake the climate plans. The required infrastructure for new wind farms in the North Sea could cost € 88 billion over fifteen years, or € 326 per person per year, leading to significantly higher energy bills for the Dutch. Something has to give. The climate is heating up, but the costs become prohibitive. That is because we believe economic growth should fund them. In other words, we think that the problem is the solution.

Sri Lanka’s Organic Farming Disaster

In the spring of 2021, Sri Lankan farmers went organic overnight. It was not their choice. The government had banned synthetic fertilisers and pesticides, a move intended to save Sri Lanka $ 400 million a year and protect Sri Lankans from the adverse health and environmental impacts of these substances. The savings were the true motive, so the Shri Lankan government planners hadn’t spent much thought on the consequences. The ban led to a 20% fall in rice and tea production. The price of rice rose by 30%, and vegetables like tomatoes and carrots by 400%. It became another blow to an economy at a time when the coronavirus pandemic had devastated the tourism industry. After five months, the government made a U-turn and reduced the restrictions. By mid-2022, the economy had gone into free fall. Inflation was above 50%, with 90% of Sri Lankans missing at least one meal per day.2 It was a total disaster. Some say organic farming is a religion.

Synthetic fertilisers make crops grow faster. Pesticides control insect infestations and diseases that destroy crops. Their adoption since the 1960s, known as the Green Revolution, has helped lift countries like Sri Lanka out of poverty. In Sri Lanka, rice yields tripled. Synthetic fertilisers and pesticides, however, ruin our health and the environment. Soil degradation endangers our food supplies. Still, discontinuing the use of fertilisers and pesticides can lead to famine. So, can organic farming feed the world?

There is also the issue of agricultural subsidies. In developed countries, governments subsidise farmers to purchase fertilisers and fuel their tractors. Of the total energy in maize produced in high-input agriculture, about 70% comes from fossil fuels. The manufacture of chemical fertilisers takes more than 30% of this energy. Cleaning the groundwater from excess fertiliser nitrates may be so costly that it will be impossible.3 When these subsidies disappear, less intensive farming methods become more economical. That will make food more expensive, and poor people can barely afford to pay for food already.

Organic farming requires twice as much land for the same output. There could be ten billion people by 2050, so the world’s farmers may need to increase their production even further. That is, unless we change our diets. Livestock takes up nearly 80% of global agricultural land, while it produces less than 20% of our calories.4 Holy cow! Meat and dairy are also a religion. By reducing our meat and dairy consumption and finding alternative ways to obtain the nutrients found in these foods, we may be able to feed the world through sustainable or organic farming methods.

Goodbye, fossil fuels?

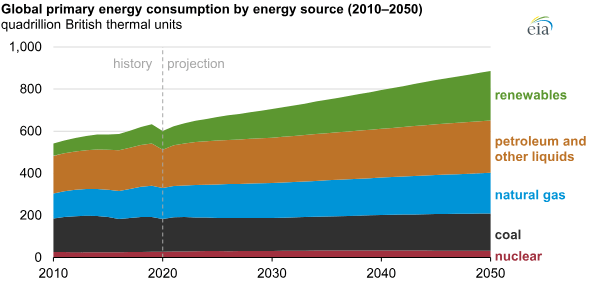

Fossil fuels provide 80% of the world’s energy needs. Perhaps you have heard fairy tales from fantasy land about phasing out fossil fuels, that solar is the cheapest source of energy, and that it will all be nice and dandy with solar and wind. A 2021 International Energy Agency (IEA) projection of future energy use tells a different story. The IEA expects a 30% increase in world energy use between 2020 and 2050. Renewable energy will not even fully cover that increase.5 We don’t hear much about it, but that’s why Big Oil keeps drilling. Saying goodbye to fossil fuels and switching to renewable energy begins with reducing global energy consumption by 30 to 50%, requiring drastic lifestyle changes.

The IEA concludes that the pledges by governments to date—even if fully achieved—fall well short of what is required to bring global energy-related carbon dioxide emissions to net zero by 2050 and give the world a 50% chance of limiting the global temperature rise to 1.5 °C.6 In plain language, we either face doom or are among the survivors of a climate disaster. The IEA presented a plan to achieve net-zero carbon emissions by 2050. It bets on cheaper solar energy and technology to store it. The problem with these plans is that achieving 50% renewable energy usage may be feasible, but beyond that, the costs will likely become prohibitive. And we are about to find out.

A global power grid could make switching to renewable energy feasible when combined with drastic reductions in energy consumption. It is possible because we don’t need most of the things we produce and consume. Long-distance electricity transport incurs limited losses (26% per 10,000 kilometres), and solar is the cheapest energy source. It might become profitable to transport electricity over thousands of kilometres from locations where solar energy is available to places where it is not. It further requires a global government due to the political risks posed by the interests of nation-states.

We may have already surpassed the 1.5 °C global temperature rise, at which point things supposedly become critical. We don’t know that, of course, but it is the best guess scientists can come up with. Scientists have been wrong often, but have been right even more often. Modest lifestyles are the way out. Forget about air travel, cars, central heating, and other luxuries that make our lives comfortable. When we have fewer children, future generations will face fewer stark choices. As long as we have enough, our lives need not be miserable. Still, the change demands sacrifice like a war effort. We don’t know the future, so our choices are a matter of faith.

The future is not ours to see

We are religious creatures who live by stories. These stories help us survive. Our beliefs enable us to collaborate on shared interests. Humans have always lived in groups on territories that they had to defend against other groups. It is how humans have lived for ages, so it is a natural behaviour to allow more strangers in to strengthen our group or to see strangers as a threat. To make us act, we need a fairy tale like the multicultural society being wonderful and its opponents being evil racists or the replacement conspiracy theory that alleges that the evil elites plan to replace white populations with non-whites in Europe and North America through mass migration and lowering the birth rate of whites. The adherents of the replacement theory use terms like ‘white genocide’ and call immigrants ‘invaders who come to rape and pillage.’

The theory is so flimsy that it may seem strange that rational people would believe it. Most immigrants flee from a miserable situation and want to live in peace and have a job. But not everyone succeeds. However, mass migration is not without problems as the immigrants come from areas with different norms and values. There is a proliferation of violent gangs, and more people feel unsafe. The rationality of a belief comes not from its correctness but from our survival. If another tribe entered your territory, it often meant death and destruction, so these feelings are natural. The primary reason for these views to become more common is not racism, which has always been there, but a growing sense of uneasiness about the number of immigrants and the trouble that they can cause.

In most cases, these fears are overdone, but not always. Crime levels among immigrants are higher. Since the 1960s, the ethnic makeup of several Western countries has undergone profound changes. If I look out the front window of my home, I can’t always tell which country I live in by looking at the people walking there. I don’t live in Amsterdam, but in a small regional centre in a rural area. I live close to an asylum seeker centre, but not all those people live there. Migrants risk their lives by leaving their homes to find a better future elsewhere, so I don’t harbour any ill-will towards them. I see people of different ethnicities mixing, mostly in good spirits. That doesn’t happen everywhere, but what I observe indicates that it could be that way.

Most immigrants aren’t asylum seekers, but people who do manual labour the Dutch don’t like to do or those who do jobs in tech corporations the Dutch can’t do. The pace of immigration causes distress among the Dutch, so the anti-immigration party has gained followers. Over the last twenty-five years, approximately 3.5 million people have migrated to the Netherlands. The people who have come to the Netherlands since 1960, along with their descendants, now comprise about 25% of the population.

The underlying problem, however is, and that truth is so politically incorrect, that no one says it, is that many immigrants don’t like live on a sustainable consumption level like they did, but desire to become excessive consumers like the Dutch, whose Earth overshoot day around the first of April, so that the Dutch consume four times as much as is sustainable. Had that not been the case, there wouldn’t have been that much immigration. And many Dutch feel poor already with that excessive lifestyle, so they don’t want to share it with foreigners, nor do they want immigrants, nor do they want to fund development aid.

There is a shortage of homes because the Netherlands has shifted from socialist building projects based on projected needs to a market-driven approach, leading to a significant drop in construction and an explosion in rents. Later, a court ruling halted construction projects because nitrogen emissions were harming the environment. Many Dutch people can’t find a home. And immigration makes it worse. Immigrants also have more children than the indigenous Dutch on average. And so, the replacement is in full progress. If the current trend persists, the descendants of the original Dutch will be a minority in the Netherlands by the end of the century. It can work out fine, but also when it does, mass migration can erode societal cohesion, making people feel less connected to each other.

We usually benefit from peace and cooperation, including migration. We welcome foreigners as they can strengthen our tribe. We also fight tribal wars, so foreigners can become a threat when they become disloyal. We don’t know the future, and it’s better to be safe than sorry. We often act on hunches. We are that way because the genes of those who survived spread. That includes the genes of those who committed genocide. The genes of their victims died out. And so, our choices are a matter of faith, especially on the issue of migration, as it is about who we can trust. Those who don’t worry about mass migration are naive. Science can’t predict tomorrow’s headlines, let alone what happens a few decades from now. And what seems rational depends on the future you expect.

Had the Native North American tribes in 1650 rallied around a strong leader who claimed whites were an evil race with nefarious inclinations, not humans, but subhuman trolls from a dark place where the Sun never shines who were planning to take their land, and united to eliminate these pale abominations, they might have fared better in the following centuries. So, if you see people giving the Hitler salute, think of the fate of Native North Americans. It helps you understand why they do it. Hitler led his people to destruction. And so did the Native American leaders who violently opposed white immigration into their lands. But had the natives succeeded in killing the whites and prospered in the following centuries, critics might later have argued that it had been unnecessarily cruel to genocide these pale-faced ones.

The rear-view mirror pundits are a particularly annoying species. They can predict the past with uncanny precision. And that makes them think they are so smart. We can’t foresee the long-term consequences of migration. It can lead to civil war, but so can divisive politics. In Bosnia, Eastern Orthodox people, Catholics and Muslims have lived relatively peacefully alongside each other for five centuries until the 1990s, when they fought a bloody civil war. The Bosnians shared the same ethnicity, culture, and language, differing only in their religion. Nationalist and religious politics plunged them into war. But had they not lived together, the war would also not have occurred.

Nationalists like to stress what goes wrong, while multiculturalists want to point out what goes right. The replacement theory can incite violence, but so can multiculturalism. In 2002, a left-wing extremist assassinated a Dutch anti-immigration politician after another had been permanently handicapped in a previous attack sixteen years earlier. In 2011, a Norwegian right-wing terrorist assassinated 77 people in a bid to prevent a ‘European cultural suicide’. There are plenty of examples of far-left and far-right violence.

The modern version of multiculturalism is also a myth. Multicultural societies supposedly comprise people of different races, ethnicities, and nationalities living together in the same community, where individuals retain, pass down, celebrate, and share their unique cultural ways of life, languages, art, traditions, and behaviours, or so we are told. It is often not a reality. Ethnic groups frequently reside in separate quarters in large cities. Cultural differences can lead to conflict. Chicago has separate neighbourhoods for whites, Mexicans, blacks, Poles, Koreans, Jews, Indians, Italians, Greeks, and they all have their neighbourhood grocery stores. The purpose of the multicultural fairy tale is to provide a story that maintains the peace long enough for us to work out our differences. Most immigrants find a place in society, so there is as much reason to believe in multiculturalism as in the replacement theory.

The underlying causes of mass migration are political and economic, such as poor governance in low-income countries, and ‘value-adding’ activities in high-income countries that drain the labour pool. If more people make money through lawsuits, advertising beauty products on social media, or trading crypto, you’ll need to bring in people to do the cleaning and work the fields. The current system creates a global competition of everyone against everyone in many essential activities like agriculture, so that it is hard to make a living outside areas with value-added bullshit. You may make more cleaning hotel rooms in Miami than carpentering or working on the land in El Salvador.

It is the social and political arrangement of nation-states and modern capitalism, creating concentrations of ‘value-adding’ nonsense activities that drive migration because that is where the money is. Everywhere else, there is a race to the bottom. Mass migration is undesirable simply because misery drives it. Ending it requires a world government and eliminating competition in essentials, thereby severely limiting global trade in essential items that people can produce locally. Replacing money with barter and solidarity is a way to make that happen, but that would also end civilisation as we know it. Taxing long-distance trade and financial transactions rather than labour is a less radical alternative.

What is our religion?

Once we have accepted a myth, it becomes a matter of faith, and we ignore evidence to the contrary or interpret facts to make them fit our beliefs. In this way, we develop tunnel vision and see only one way out. When the Dutch began electrifying their energy consumption, few foresaw that they might end up needing more power plants rather than fewer, just in case there was no solar and wind energy, which might happen during winter when energy demand is the highest. So far, the consequences have remained limited. The Sri Lankans suffered much more from their sudden switch to organic farming. But we might accept the consequences if we believe these choices are the right ones.

Your future and your children’s are on the line, so making the right choices is a matter of survival. And so, it is natural to have strong feelings about matters like renewable energy, organic farming or migration, and rally around stories that can generate the collective action you think is needed. We believe in stories such as nationalism, multiculturalism, progress, collapse, science, and Christianity. Whether it is the truth or a myth doesn’t always matter. We don’t know the future, so our choices are a matter of faith. Past generations believed in progress and that the future would be better. Still, material wealth and new technologies didn’t bring happiness.

In the Middle Ages, most Europeans were dirt poor. Their houses were mere sheds. Still, they built magnificent cathedrals. Rich people spent their money on cathedrals rather than investing it for profit. God was more important to them. Were they right, or were they wrong? Today, money is our religion. Whether to switch to renewable energy or organic farming has become an economic calculation. But can you serve both God and Mammon? Renewable energy, organic agriculture, and a global multicultural society are choices of faith, but so are the alternatives. They can go wrong as well, and probably will. We can never be sure that we make the right choices. We can only do the best we can using the information we have. And if God has written the script, we can only play our role in it.

Latest revision: 22 August 2025

Featured image: The Lady Chapel of Exeter Cathedral. User Diliff. Wikimedia Commons.

1. ‘This is nuts:’ European power prices go negative as springtime renewables soar. Joshua S Hill (2023). Renew Economy. [link]

2. Sri Lanka’s organic farming disaster, explained. Kenny Torrella (2022). VOX. [link]

3. Can conventional agriculture feed the world? Pablo Tittonell. Wageningen University.

5. How much of the world’s land would we need in order to feed the global population with the average diet of a given country? Hannah Ritchie (2017). Our World In Data. [link]

5. EIA projects nearly 50% increase in world energy use by 2050, led by growth in renewables. EIA (2021). [link]

6. Net Zero by 2050: A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector. IEA (2021). [link]