Identity groups building society

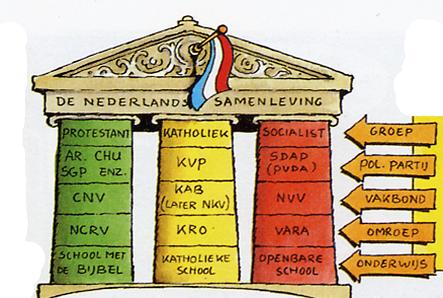

Dutch society long centred around identity groups based on religion or ideology. The Dutch call it pillarisation. A pillar is vertical, so it encompasses several social classes. Social life was within your identity group, and you had few contacts with outsiders. These pillars had sports clubs, political parties, unions, newspapers, and broadcasters. Roman Catholics and Protestants also had schools and hospitals.

The pillars of Dutch society were Protestant, Roman Catholic, and Socialist, with each about 30% of the population. The Protestants themselves consisted of smaller groups that had their specific views on the Bible. The remaining 10% of the Dutch were liberal. The liberals were less organised and opposed pillarisation, but they also had political parties, newspapers and broadcasters.

Strong communities are close-knit, have shared norms and values based on ideology or religion, and come with social obligations. The pillar organisations focused exclusively on their communities. Similar arrangements existed in other countries. In the Netherlands, none of these groups dominated society. And the shared Dutch identity and the state made these relationships cooperative. In other words, Dutch society was built on pillars.

The Dutch were famous for their tolerance, which was at times close to indifference. The identity groups accepted each other and minded their own affairs. After 1800, there was no civil war in the Netherlands, nor was there a threat of one at any time. Leadership played a significant role. The leaders of the pillars were willing to compromise, and the members merely followed their leaders, guaranteeing peaceful relationships within society for two centuries.

Still, identity issues dominated Dutch politics from time to time. On 11 November 1925, the cabinet fell when the Catholic ministers resigned after Parliament accepted an amendment introduced by a small Protestant fraction to eliminate the funding for the Dutch envoy with the Vatican. A Protestant government fraction supported the amendment.

None of the identity groups on its own was able to dominate society. Instead, they had to make deals with each other. On religious issues, Roman Catholics and Protestants found each other. For instance, they arranged that schools and hospitals could have a religious identity and that the state would fund them like public schools and hospitals. The Socialists made deals on working conditions and social benefits with Catholics and Protestants.

Pillarisation in the Netherlands began to take shape at the close of the nineteenth century. One could say that Dutch society was built upon the pillars. They allowed groups with different views and cultures to coexist peacefully and gradually integrate. From the 1960s onwards, the pillars began to lose their meaning, and the Dutch became one nation. Pillarisation can be helpful if you believe in a shared destiny, for instance, the nation-state, but have different backgrounds that prevent integration in the short term. In this sense, it works like multiculturalism.

Pillarisation can be helpful if people believe in a shared destiny, for instance, the nation-state, but do not share a common background. In that case, everyone can live and work together with the people they feel comfortable with. Cultural and religious differences may subside over time. But as long as these identities remain distinct, people can organise themselves accordingly via pillars, and in doing so, avoid conflict.

Latest update: 19 May 2023