The miracle of capitalism

A few centuries ago, over 99% of the world’s population lived in abject poverty. In 1651, Thomas Hobbes depicted human life as poor, nasty, brutish, and short. It had always been that way. Yet, a few centuries later, a miracle had occurred. Nowadays, more people suffer from obesity than from hunger. The life expectancy in the poorest countries exceeds that of the Netherlands in 1750, the wealthiest nation in the world at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. This miracle is the result of science, innovations and a massive build-up of capital. How could that happen? That is because interest rates have come down from 30% in the Middle Ages to near zero today. Only, what caused interest rates to go that low?

In the economic sphere, it is the outcome of an epic battle between ‘Time Preference’ and ‘Capitalist Spirit’ that raged for centuries. The capitalist spirit won. Ordinary people suffer from a condition known as time preference, which causes them to spend their money on frivolous items. They think, ‘Live today, because you can be dead tomorrow.’ Economists say they lack trust in the future. There are also capitalists, who are special people who suffer from an illness called the capitalist spirit. Rather than spending their money on frivolous items, they think, ‘Don’t live today, but invest, so you will have more money when you die.’ Economists say that they have trust in the future.

And so, capitalists save and invest while ordinary people work for them and buy the products and services their ventures produce. When time preference prevails, there are few savings and high interest rates. People are poor because there is a lack of money for investments. When the capitalist spirit prevails, there are ample savings, low interest rates, and wealthy individuals with excess capital to invest. This miracle wouldn’t have happened without low interest rates, as investment returns must be higher than the interest rate, and interest rates can’t be low without efficient financial markets and trust in political and economic institutions. So, how did that come about?

In the Middle Ages, Europeans gradually developed a capitalist spirit. The ethic of the merchant gradually spread, so that money and profit, rather than Christian values, came to drive Europeans. They found new trade routes and exploited their colonies. Initially, Spain and Portugal led the way, but their kings were short of cash and heavily taxed their people. Many merchants moved to the Dutch Republic, which was more business-friendly because the propertied classes ran it. The Dutch didn’t have a strong state with an army, so taxes were also lower. The Dutch invented the stock market, featuring publicly traded shares, a crucial financial innovation that helps manage risk. Since then, investors could invest in a corporation at any time and sell their investment at any time.

Later, Great Britain became the dominant power. The British business elite, who paid most of the taxes, didn’t like paying for incompetence and corruption. After they had gained control over the British state in the Glorious Revolution of 1689, they forced the state to improve its competence. The British invented fractional reserve banking with a central bank, thereby creating efficient financial markets. Their colonial empire also expanded, so that they came to control the largest market, which favoured economies of scale. Once the competent government and financial innovations were in place, the Industrial Revolution took off. Low interest rates made long-term investments in machines profitable.

Once interest rates had decreased, economic growth accelerated, enabling investment returns to cover interest payments, which allowed financial markets to expand and drive further growth. The capitalist miracle is that financial markets helped boost trade and production by creating money that doesn’t exist to start businesses that don’t yet exist to make products that the people those businesses will hire will buy with this newly created money. Financial markets are at the basis of the capitalist economy. When growth slows, interest-bearing debt may collapse the global economy, but so far, financial innovators have invented new schemes to lend more, helped by low interest rates. Low interest rates make an economy possible, not high ones. But trust makes low interest rates possible.

Usury: the hidden cancer

As long as there was growth, there was more for most people, even though the division of the fruits of capitalism has its shortcomings. Personal qualities explain some inequality. Some people work harder, some are better entrepreneurs, some are more frugal, some are more useful, and some are better at exploiting others for their personal gain. These people usually end up wealthier. Still, the primary driving force in the capitalist system has little to do with individual qualities. It is profit or interest. Interest comprises all returns on capital. Interest is the reason why the rich get richer at the expense of the rest of us.

Interest fuels a global competition driven by innovation and economies of scale. As a result, a few oligarchs have become exceptionally wealthy, often by cornering markets, such as in the tech sector. Wealth inequality will be the most urgent immediate challenge once there is less to go around. It is unacceptable that people are starving because of a fuel shortage while the elites fly around in their private jets. Today, the increased use of artificial intelligence drives up energy prices, pushing humans out of the energy market.

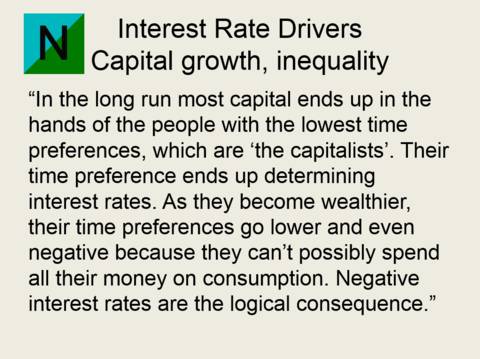

Interest rates emerge in a market. Credit in the banking system and the actions of central banks have a profound influence, making financial markets more efficient. Still, supply and demand in financial markets remain key factors. Silvio Gesell had already envisioned, in 1916, that efficient global financial markets would eventually drive interest rates to zero. He based his prediction on the observation that interest rates were the lowest in London, which had the most developed financial markets at the time.

Wealth inequality, caused by decades of neoliberal supply-side economic policies, also plays a role. Gutting labour rights and social benefits to lower taxes for the rich caused their wealth to trickle down via lower interest rates. The wealthy, awash in capital, have run out of sensible investment options because working-class people lack the funds to spend. And so, interest rates decreased, allowing the working class to borrow more, propping up the economy with asset bubbles, in yet another usurious scheme in which the rich exploit the rest of us. Adding mortgage debt has long helped keep several economies afloat, including the Netherlands’.

Most people pay more interest than they receive. We pay interest via rents, taxes, and the price of everything we buy. Interest works like a tax on poverty that the poor pay for the benefit of the wealthy. Lower interest rates could benefit most people by lowering prices. You don’t see that happening. In a usury-based financial system, lower interest rates allow us to borrow more, putting more money into circulation and raising prices. As we borrow more, we may end up paying even more interest. To improve their yields in a low-interest environment, capitalists invent new schemes, such as leveraged buyouts and vampire capitalism. Lower interest rates also enabled more predatory lending because they made loan-sharking profitable at higher default rates.

Lower interest rates have worsened the excesses in the financial system. That is because we live under a usurious financial system. Had the maximum interest rate been zero, loan-sharking and leveraged buyouts wouldn’t be possible. But that would require us to look after people in financial trouble and limit their freedom, rather than giving them the liberty to borrow from payday lenders and credit card corporations. The underlying problem is the merchant’s ethics, which has become the foundation of our moral system, which is no ethics at all. A world without merchants is a world without many comforts we take for granted, but trade also makes us dependent on a system of governments and markets. Interest plays a crucial role. Investments must at least return the prevailing interest rate. Things aren’t straightforward, so ‘interest is evil’ is not a helpful approach to the matter. But what precisely is usury?

What is usury?

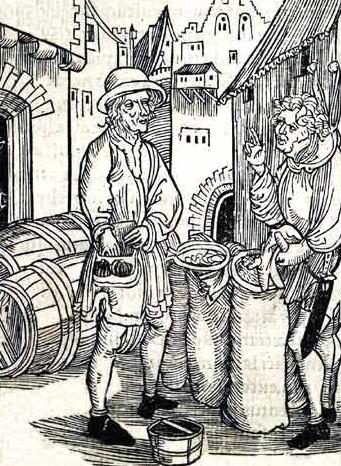

When you ask someone what usury is, the answer might be charging an excessively high interest rate. Traditionally, usury referred to paying for the use of money. In other words, usury is charging interest on loans. In this traditional definition, the currency has a constant value, so the borrower must repay the same value. If a ruler debases the currency and halves its gold content, a lender has a legitimate claim on the same amount of gold, hence twice the amount of currency. The reasons why usury is damaging are:

- Usury turns money into a tool of power, enabling the rich to exploit the poor.

- Usury disrupts the circular flow of money, causing economic hardship.

- Fixed interest payments cause financial instability as incomes fluctuate.

Making a profit from a business venture is not usury. However, all capital income is interest, and interest contributes to wealth and income inequality, unless the interest rate is at or below the growth rate. Capitalism has raised living standards, so the prevailing view is that its benefits outweigh its drawbacks. Today, capitalist economies excel in generating money for capitalists by turning energy and resources into waste and pollution to market non-essential products and services in the bullshit economy. Therefore, the drawbacks now surpass the benefits, and by a wide margin.

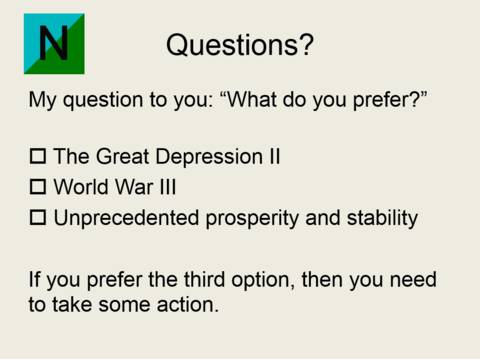

The economist Piketty found that interest rates on capital were higher than the economic growth rate most of the time.1 That is unsustainable. It requires capital destruction that creates new room for growth or lower interest rates. In the past, World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II annihilated capital and created new room for growth. And so did the end of communism at the end of the 20th century. Eastern Europe, China and India became new centres of growth. The wave of capital seeking a return has finally reached Africa, the last frontier. From now on, growth must come from ‘wealth-creating’ non-essential activities in the bullshit economy, such as data centres that run artificial intelligence.

Value standard

The idea behind banning usury is that it is unfair for borrowers to return more than they borrowed. Traditionally, the poor borrowed from the rich, so charging interest would make them even poorer. If you borrow a loaf of bread, you return it. That is simple. Money, however, is an abstract measure of value, so what is usury and what is not requires a value standard. Islam forbids charging interest on money and debts, but also prohibits the debasement of currencies. According to Islamic law, money is gold or silver. Lenders should receive the same amount of gold or silver as repayment for the loan. There is, however, no reward for the risk of lending, which impedes capital formation. It is one of the reasons why the Industrial Revolution didn’t take off in the Islamic world.

A Natural Money currency serves as the value standard, so usury refers to charging an interest rate above zero on loans. To serve as a standard, the currency must have a stable value. The value of the Egyptian grain money came from its backing by grain stored in granaries. During the gold standard, gold was the value standard, as you could exchange national currencies for a fixed amount of gold. The backing of today’s fiat currencies is the economy. The Quantity Theory of Money states that Money Stock (M) * Velocity (V) = Price (P) * Quantity (Q), so Money Stock (M) depends on Velocity (V), Price (P) and Quantity (Q), and the value of a single unit such as the euro, is M / units in circulation.

A grain or gold backing can give the currency a stable value because there is a limited amount of grain and gold. Such a limit doesn’t exist for fiat currencies. Still, Natural Money currency can serve as a stable value standard because its issuance depends on lenders’ willingness to accept negative interest rates. Lenders thus only lend when they expect the currency’s future value to remain sufficiently stable. When they don’t lend, the amount of money in circulation shrinks due to negative interest rates and debt repayments, allowing the currency’s value to increase and prices to decrease. Trust in the currency thus stems from persistent deflationary pressures, as negative interest rates consume the money supply, and the maximum interest rate constrains credit creation.

Efficiency argument

Today’s global economy is overcapitalised due to massive over-investment in the bullshit economy, so near-term future growth rates will probably be negative, either as the result of an involuntary collapse or a managed decline, and the sustainable interest rate will also be negative. Once the world economy is on a sustainable footing again, there may be sustainable growth, allowing growth rates to become positive once more in the more distant future. A stable economy operating near the maximum growth rate, which can be negative, can achieve its full potential and full employment. That is what the ‘miracle of Wörgl’ suggests.

When average investment returns are near their sustainable maximum, real interest rates are also near their sustainable maximum. The usury-based economy is unstable due to credit expansions and contractions, so it often does not operate at its sustainable maximum, reducing its efficiency. Natural Money helps achieve a stable economy and minimise financial system risk, thereby realising the sustainable maximum. It follows that real interest rates with Natural Money are higher, even when economic growth rates are positive. The maximum nominal interest rate is zero, so higher real rates show up as currency appreciation, allowing an interest rate of zero to yield a positive absolute return.

A simple calculation illustrates this view. Economists assume there is a link between the amount of money and money substitutes (M) in circulation and prices in the equation Money Stock (M) * Velocity (V) = Price (P) * Quantity (Q). If ΔP, ΔM and ΔQ are sufficiently small, and velocity is constant, so that ΔV = 0, then it is possible to approximate this equation with %ΔP = %ΔM – %ΔQ, where %ΔP is the percentage change in price level, %ΔM is the percentage change in money stock, %ΔV is the percentage change in money velocity, and %ΔQ is the percentage change in the quantity of production.

The velocity of money (V) for Natural Money might be higher than for interest-bearing currency, and that could go together with a smaller money stock (M). Still, the velocity is likely to remain constant, as the economic picture is expected to remain stable. Now, it is possible to calculate the real interest rate (r) as the nominal interest rate (i) minus the inflation rate (%ΔP), so that r = i – (%ΔM + %ΔQ).

Suppose the long-term average economic growth rate for interest-bearing money is 2%. For Natural Money, it might be 3% because the economy is more often performing at its maximum potential. Assume that the long-term average money supply increase for interest-bearing money is 6% per year. For Natural Money, it is 0%. The long-term price inflation rate could then be 4% for interest-bearing money. With Natural Money, there could be a price deflation rate of 3% as the economy grows at a rate of 3% with a stable money supply. We can then produce the following calculation:

| situation | interest on money | Natural Money |

| nominal interest rate (i) | +3% | -2% |

| change in money supply (ΔM) | +6% | 0% |

| economic growth (ΔQ) | +2% | +3% |

| real interest rate (r = i – ΔM + ΔQ) | -1% | +1% |

Economic growth can be higher with Natural Money, allowing real interest rates to be higher. Furthermore, because Natural Money has several stabilisers that reduce financial system risk, the level of risk is likely lower. As a result, the risk-reward ratios associated with Natural Money are better than those in the current usury-based financial system. In other words, the same real interest rate in a usury-free financial system is a better deal because it entails fewer risks. Hence, a usury-free financial system based on Natural Money is more efficient, so there will be a capital flight from the usury-based economy to the usury-free economy after implementing Natural Money on a large enough scale. The efficiency argument demonstrates that usurious finance is parasitic.

The real interest rate may improve more than the economic growth rate due to lower financial-sector profits from phasing out exploitative parasitic activities, such as interest-bearing consumer credit. The rationale is that, without credit card payments, consumers have more disposable income. Furthermore, economic and financial stability can reduce investment risks, thereby requiring less financial sector intermediation. The financial instability and the need for government and central bank interventions in the usury-based financial system create opportunities for politically connected and other savvy and informed individuals, often referred to as ‘parasites’, to enrich themselves at the expense of the general public. The higher efficiency of Natural Money could end that.

The efficiency argument still applies when we switch to a values-driven, people-friendly economy that operates in harmony with nature. The inefficiency of such an economy stems from its inferior ability to generate money for investors by transforming energy and natural resources into waste and pollution in the bullshit economy. That depresses interest rates. That is not an inefficiency in the financial sector. With Natural Money, a values-driven, people-friendly economy can remain operational thanks to the financial system’s efficiency. Terminating the bullshit economy in a usury-based financial system will also depress interest rates. That can bring about an economic collapse, because usury makes capital addicted to growth.

Trust

Someone once asked me on an Internet message board, ‘Why would I lend money interest-free?’ The borrower may not repay. So, why take that risk? We lend interest-free to people we trust, and we may lend to family and friends, even when they are untrustworthy individuals living off our money. After all, they are family and friends. In a market, it won’t happen unless we trust the currency and the borrowers. Hence, ending usury is only possible in a high-trust environment. And investors must be in the market for other reasons than maximising their profits. Those who lend money to organic farms and invest in renewable energy have a different view of investing than vampire capitalists, who scam the government and rob grandparents of their retirement savings.

Credit means trust. Trust in the future is the foundation of the capitalist economy. Investors imagine that the future will be better so that their investments will be profitable or at least not loss-making. Credit, or financial capital, reflects this trust. Most of our money is credit, so its value depends on an imagined future. Some people argue that credit, banking, and central banking are a fraud because they are a fantasy. They may prefer something tangible, such as gold. Indeed, the capitalist economy, as well as civilisation in general, demonstrates the power of human imagination, and our faith in what we believe.

To have trust in the future, investors must believe that their investments are safe. The rule of law, political stability, the absence of graft, and sensible economic policies are fundamental factors for the economy to function effectively. As investments, such as factory investments, are long-term, the risk that a government will annul earlier commitments is a critical factor in investment decisions. Government actions, such as asset confiscation or taxation, can deter investors. Differences in tax regimes are equally damaging, as tax havens parasitise on productive economies that collect taxes to invest in their infrastructure and education.

Interest rates are the lowest in stable countries with low inflation, as trust translates into a risk premium on investments. The greater the perceived risk, the more the future becomes discounted, the higher the interest rates are, and the lower the standard of living usually is. Hence, Switzerland and Sweden have low interest rates, while Argentina and Mozambique have high interest rates. Interest rates in Europe are lower than in the United States. Apart from lower growth expectations, the Stability and Growth Pact, which limits government deficits, plays a role. And the government deficit as a percentage of tax income is a better indicator of the health of government finances than the deficit as a percentage of GDP. These are more sustainable in Europe. And so, trust also plays a role here.

Interest rates in Switzerland are currently at their lowest. In 2025, the key interest rate stands at zero. Interest rates in Switzerland are that low because investors trust the Swiss currency. From 1990 until 2024, the government’s budget deficit averaged at 0.45% of GDP. At the end of 2024, government debt was 20% of GDP. A general rule is that the lower the trust in the currency, the higher the interest rate. Venezuela has the highest interest rate at 60%, but with an inflation rate of 180%, investors are better off with a yield of zero in Swiss francs. In a market, low interest rates signal trust. Hence, trust is a crucial prerequisite for ending usury.

In 2025, interest rates in Turkey exceeded 40% to curb inflation after a failed monetary experiment. The assumption that interest charges cause inflation led Turkey’s leader to force the central bank to lower its interest rates. Inflation soared to 85% in 2022. The Turkish leader was defrauding creditors, thereby transgressing Islamic law. The relationship between interest and inflation exists, but it operates via credit. Credit expansion causes inflation, not interest itself. In a usury-based financial system with fiat currencies, raising interest rates curbs inflation by dampening demand for credit. That obscures the truth that interest is a cause of inflation, but a better way to limit credit expansion is to set a maximum interest rate on loans.

With Natural Money, the central bank doesn’t set the interest rate or manage the money supply. The interest rate and the money supply emerge in the market for lending and borrowing. The holding fee on the currency provides a stimulus by making lending at negative interest rates attractive, so no money remains on the sidelines. At the same time, the maximum interest rate of zero provides austerity, curtailing credit during a boom or when inflation is high. That will cool down the economy and dampen inflation. There could be deflation, and deflation could be permanent. The market for lending and borrowing is free in the sense that the central bank doesn’t manage interest rates and the money supply. However, the maximum interest rate of zero operates as a price control.

Interest rates emerge in the market for lending and borrowing. Negative interest rates require trust in the currency, the government and its policies, the financial system, and, ultimately, in the borrowers. It requires trust in the political economy and the future. In other words, all the world’s governments must be as reliable and capable as Denmark’s, and the global economy must be on a sustainable footing. At the same time, market participants shouldn’t engage in scams. So far, business and ethics haven’t agreed very well. The ethic of the merchant is no ethic at all. The change requires a moral imperative. We shouldn’t harm other people or nature. Instead, we should see the consequences of our actions and change our ways. Only a new religion can make that happen.

The price of usury

Interest promotes wealth and income equality. Most of us pay more in interest than we receive, either directly through loans and rents, or indirectly through the products we purchase. German research from the 1980s showed that the bottom 80% poorest people pay interest to the top 10% of the wealthiest people. You can view interest as a tax on the poor paid to the wealthy. The wealthiest individuals reinvest most of their interest income. That is what made them rich in the first place.

Interest promotes short-term thinking. The pursuit of profit drives the transformation of energy and resources into waste and pollution in the bullshit economy. With positive interest rates, money in the future is worth less than money now. It affects investment choices. Without interest charges, long-term investments would become more attractive. When interest rates are high, cutting down a forest today, selling the wood, and investing the proceeds may give higher financial returns than sustainable forest management.

Incomes fluctuate against fixed interest charges. It can bring borrowers into trouble. Financial instability can lead to economic instability. Usury causes financial crises, recessions and depressions. Governments and central banks manage the problem, but their actions create a false sense of security, allowing debts to continue growing, which will ultimately lead to a financial apocalypse. The underlying cause is usury. However, the road to the end of usury also goes through financial innovation and modern finance.

Fractional reserve banking

Innovations in financial markets have made them more efficient, enabling lower interest rates and increased lending, thereby spurring the Industrial Revolution. A crucial invention was fractional reserve banking. It turned bank deposits into money. There is always a demand for money. It is the most liquid asset. Economists call it the liquidity preference. Money commands power. You can use money to buy anything at any time. We may want to keep cash at hand for expected purchases, unexpected expenses, and investment opportunities.2 And so, we often aren’t willing to lend our money.

Fractional reserve banking enables banks to lend out money that depositors can withdraw. If you lend money to a fractional reserve bank, you can use it at any time, as if it were cash. Banks kept a fraction of deposits in cash reserves to meet withdrawals, knowing that only a small share of depositors would withdraw their money. That freed up funds for investments and helped to lower interest rates. A fractional-reserve bank creates money because a new loan automatically creates a new, equal-sized deposit. And that deposit is like any other deposit. You can use it to make a payment or withdraw cash. Fractional reserve banking eroded the commanding power of money, resulting in lower interest rates.

Fractional-reserve banks can fail when a large number of depositors withdraw their funds at once. The integrity of fractional-reserve money depended on the ability to exchange deposits for cash. That is where central banks come in. They can help banks in times of trouble by printing additional cash and lending it to them at interest. That safety net reduced the risk associated with bank deposits, allowing interest rates to drop even lower, which, in turn, promoted more lending and economic development.

If it sounds too good to be true, then it usually is. Lower interest rates fuelled the economic boom since the Industrial Revolution, which will eventually lead to a technological-ecological apocalypse. Critics of fractional reserve banking and central banking further argue that lower interest rates encourage poor investment decisions and that the safety net provided by central banks creates a moral hazard. If interest rates were to rise, these investments would become unprofitable, leading to bankruptcies and unemployment. And if central banks rescue banks in times of trouble, it will promote irresponsible lending.

There is overcrediting, and lower interest rates promote irresponsible lending by increasing profit margins for usurious lending. The way to end usurious lending is to set a maximum interest rate. More recently, critics have argued that central banks, through extraordinary measures such as quantitative easing, have suppressed interest rates. However, central banks believed that interest rates were too high. They couldn’t lower them due to a price control called the zero lower bound, which distorts the market. By printing money, central banks aimed to generate inflation, thereby allowing them to raise interest rates later.

Reserve requirements

Banks hold reserves, which are money issued by a central bank. Reserves include banknotes and coins, as well as balances that banks hold at the central bank. The primary reason for holding reserves was to meet cash withdrawals from depositors or to make payments to other banks in case depositors transfer money to another bank, and the other bank desires payment in kind rather than an IOU. A reserve requirement is a liquidity requirement. A bank must have enough cash on hand to meet its short-term obligations. Two developments have profoundly affected the need for reserves:

- Contrary to the past, depositors hardly ever withdraw their funds in cash, so the money stays within the banking system.

- Government debt has become an alternative source of liquidity. Government debt issued in the government’s currency is as safe as cash.

A government can guarantee repayments of debts issued in its own currency by printing more currency, with a so-called independent central bank as a cover, which has become a core foundation of confidence in the current usury-based financial system. The central bank will not let the usury-based financial system fail, so it will print money to buy government debt, which reduces the supply of debt and increases the supply of currency by which to buy government debt, thereby lowering interest rates and allowing the government to borrow more, making new money available to pay interest.

These profound changes have made traditional reserve requirements largely redundant. Banks hardly need any cash in their vaults. If they pay another bank in kind, government debt is as good as central bank currency. Or a bank could borrow at the central bank or another bank and pledge government debt as collateral. The experts concluded that reserve requirements have become superfluous. Government debt has become the actual reserve. And so, banking regulations today focus on solvency, or the ability to meet long-term obligations. Still, it would be a most serious oversight to ignore liquidity.

Globalisation, liberalisation, and derivatives

Advances in information technology and financial innovations have driven the globalisation of financial markets over the past few decades. In the 1980s and 1990s, governments liberalised financial markets and removed capital controls. Capital controls can lead to higher interest rates and higher costs of capital.3 Globalisation and liberalisation expanded the possibilities for borrowing and lending worldwide.4 The increased competition reduced the price of financial intermediation.

Globalisation and liberalisation made financial markets more liquid. It became cheaper and easier to exchange financial instruments, such as bonds and stocks, as well as goods and services, for cash. This development is more commonly known as financialisation. Like fractional reserve banking, financialisation eroded the position of money as the most liquid asset, thereby diminishing the commanding position of money owners to demand interest.

Globalisation and liberalisation also caused trouble. Money and capital could move more freely, making it easier for changing expectations to lead to financial instability. Central bank interventions neutralised a series of financial crises in the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s. Lower interest rates prompted investors to seek higher yields and take on more risk. However, trust and, therefore, liquidity can suddenly evaporate. Some countries used capital controls to counter financial instability while central banks provided liquidity.

Innovations in risk management and derivatives enabled the financial sector to further increase lending. These innovations spread risk, allowing the total amount of risk in the system to grow. Due to a lack of regulatory oversight, derivatives also enabled scammers to sell fraudulent mortgages, contributing to the 2008 financial crisis. Still, banks that professionally used derivatives to hedge their risks weathered the crisis better and had fewer loan write-offs.5

The notional value of outstanding derivatives can be mind-boggling. Their actual value is much lower. You can best compare them with insurance policies. The notional value of your fire insurance policy is typically based on the value of your home. The actual value is the premium you pay. That is, until your house burns down, and the actual value becomes the notional value. Insurers can handle that until many homes catch fire simultaneously.

The actual value of an interest rate derivative on a 3% ten-year bond with a notional value of €1,000,000 might change by €81,109 if the interest rate increases to 4%. As long as parties use derivatives to hedge risks, and counterparties, the ‘insurers’, can absorb the losses, the system will function. An equivalent to all houses catching fire simultaneously could be a sudden increase in interest rates. When the system is more stable, the need for these instruments decreases.

Wealth effect and bubbles

Lower interest rates increase the value of assets via discounting. In theory, the price of an asset is the net present value of its future revenues. Even though that is often not the case in reality, the theory explains why the prices of assets like bonds, real estate, and stocks rise when interest rates decrease. In this sense, lower interest rates can promote wealth inequality, but only when we consider the net present value of assets. If future revenue streams don’t change, wealth inequality is merely a temporary side effect.

There was, however, another dynamic operating underneath. Lower interest rates allow consumers to borrow more by taking out higher mortgages, thereby financing their unsustainable lifestyles. Critics called it a wealth effect promoted by an asset bubble. Lending propped up consumer spending when the incomes of many working-class people were lagging, and the wealth of the rich ‘trickled down’ via lower interest rates as they were running out of sensible investment options, giving them yet another avenue by which to squeeze the working class. In a system of usury, lower interest rates are of no help.

Financial sanity

Interest compounds to infinity. Three grammes of gold at 4% interest turn into an amount of gold weighing twelve million times as much as the Earth after 2020 years. Most of us aren’t long-term planners. We are busy fixing holes rather than solving underlying problems until things fall apart. Economists do this as well. John Maynard Keynes invented government borrowing as a fix for usury-induced debt problems. He once justified his short-term thinking with the world-famous quote, ‘In the long run, we are all dead.’ And this man was the founding father of modern economic policies.

More debt has now become the standard solution for debt problems. Today, most money comes into existence as a loan on which the borrower must pay interest. Every loan creates a deposit. The depositor automatically becomes the lender. If the interest rate is 5%, and €100 is circulating, then €105 must come back. So, where does the extra € 5 come from? Here are, once again, the options:

- Depositors (on aggregate) spend some of their balance so borrowers (on aggregate) can pay the interest from existing money.

- Some borrowers default and do not return (part of) the balance.

- Borrowers (on aggregate) borrow the extra €5.

- The government borrows the extra €5.

- The central bank creates €5 out of thin air to cope with the shortfall.

Interest payments do not necessarily cause a shortage of money. Still, in reality, they do, mainly because depositors find it, like Scrooge McDuck, difficult, emotionally or otherwise, to part with their money. New debts fill most of the holes caused by the Scrooge McDuckism of depositors. That is why debt levels nearly always increase. Still, the money doesn’t always arrive at the right places, which causes financial crises. A few defaults are acceptable, but too many can cascade into a financial crisis, triggering an economic downturn or even a depression.

The cost of letting the financial system fail is so great that this is not an option. The 2008 financial crisis could have meant the end of civilisation as we know it, had central banks not saved us from a financial apocalypse caused by usury. When no one else is borrowing, the government and the central bank must step in, either by borrowing or printing money outright, to introduce new money into circulation to repay existing debts with interest. In this way, debts continue to grow, and we have become the hostages of the usurers.

The end of the road

The road to the end of usury ran through financial innovations. They lowered interest rates. Today, the world is awash in debt, and interest payments strangle the global economy, so that future interest rates may become negative. That could either be the end of usury or, if usury remains, the end of the economy. The world economy may collapse, or we can have a graceful decline, promoted by the efficiency of a usury-free financial system. The efficiency of Natural Money can help us build a high-trust world economy founded on moral values.

In a simplified world, we rely more on family and community, and less on markets and states, so the economy will also become simpler. Natural Money eliminates risk from the financial system, so that, after its implementation, several modern financial instruments may become obsolete, joining fossil fuels and marketing strategies. Still, economies of scale apply to several essential products and services, including finance. Negative interest rates require risk management that only scale can provide.

Latest revision: 3 December 2025

Featured image: Loan shark picture circulating on the internet, origin unknown.

1. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Thomas Piketty (2013). Belknap Press.

2. Keynes, John Maynard (1936). General Theory of Employment, Money and Interest. Palgrave Macmillan.

3. Edwards, Sebastian (1999). How Effective are Capital Controls? Anderson Graduate School of Management, University of California.

4. Issing, Otmar (2000). The globalisation of financial markets. European Central Bank.

5. Norden, Lars, Silva Buston, Consuelo, Wolf Wagner (2014). Financial innovation and bank behaviour: Evidence from credit markets. Tilburg University.