The road to prosperity

Until very recently nearly everyone lived in abject poverty. Most people had barely enough to survive. In 1651 Thomas Hobbes depicted the life of man as poor, nasty, brutish, and short. Yet a few centuries later a miracle had happened. Many people are still poor but more people suffer from obesity than from hunger while the life expectancy in the poorest countries exceeds that of the Netherlands in 1750, the richest country in the world in the wake of the Industrial Revolution.

In 1516 Thomas More wrote his famous novel about a fictional island named Utopia. Life in Utopia was nearly as good as in the Garden of Eden. The Utopians worked six hours per day and took whatever they needed. His book inspired writers and dreamers to think of a better world while leaving the hard work to entrepreneurs, labourers and engineers. Today many of us have more than they need but still we work hard and feel insecure about the future.

Why is that? The answer lies within the nature of capitalism. It is not enough that we just work to buy the things we need. We must work harder to buy more, otherwise businesses go bankrupt, investors lose money, and people will be unemployed and left without income. In other words, the economy must grow. That worked well in the last few centuries, and it brought us many good things, but it may be about to kill us now.

People in traditional cultures didn’t need much. They were easily satisfied. Many modern people in capitalist societies believe they never have enough. You can always go for a bigger house, a more expensive car, or more luxury items. Many of us do not need more but the advertisement industry makes us believe that we do. We believe in scarcity even when there is abundance. And so the economy must grow. That is what they tell us.

But what are the consequences of this belief? If you eat too much this is great for business profits. And if you become obese as a consequence and need drugs for that reason, you again contribute to business profits so this is even better. Meanwhile we are using the resources of this planet in a much faster pace than nature can replenish. Humanity is standing before the abyss. Civilisation as it is will not continue for much longer. The end is near.

What has this to do with interest? If we want more products and services, we need more businesses, so we need investments. To do investments, we need savings. And to make people save, we need interest to make saving attractive. Consequently investments need to be profitable to pay for the interest. But there can be too much of a good thing. If we don’t need more stuff, we don’t need more savings, and interest rates go down.

A sustainable and humane economy?

Is it possible for humanity to live in harmony with itself and nature? We work harder than ever before and in doing so we destroy life on this planet. It seems hard to change this. If you organise production differently then your products might not be sold at a price that covers the cost to make them. In a market economy the value of a product is the price it fetches in the market. Marketing often comes down to inflating the market price of a product or a service to make more profit.

In the past there have been two fundamentally different approaches to the economy. For instance, before Germany became united in 1990, there were a capitalist and a socialist Germany. Socialist Germany ensured that everyone was employed. People in socialist Germany had enough but they had little choice as to what products they could buy. For instance, in socialist Germany there were two kinds of yoghurt while there were sixty in capitalist Germany.

And there was little freedom in socialist Germany. The secret police were everywhere. When Germany became united the socialist economy collapsed. Socialist corporations suddenly were bankrupt because no-one wanted to buy the products they produced. The ensuing reorganisation of the economy led to mass lay-offs and a staggering rise in unemployment. Ultimately 60% of the jobs in the former socialist firms disappeared.

Many lives and communities in former socialist Germany were destroyed. And people suddenly felt insecure about their future as businesses had to compete and make a profit in order to survive. In a market economy efficiency considerations determine what is produced. These efficiency considerations are the result of customer preferences as well as the requirement to make a profit. Loss-making businesses usually can’t attract capital in a market economy.

The quest for efficiency results in fewer and fewer people producing the things we need. To keep everyone employed in a capitalist economy unnecessary products and services must be produced, causing a rapid depletion of scarce resources as well as lots of waste. At least in theory we work can a few hours per day so we have more time for our mobile phone and each other. It may also be possible to free up resources to address poverty and other social problems.

And what has this to do with interest? The profit a corporation is expected to make should be higher than the interest rate in the markets for money and capital. Because what’s the point in making the effort and taking the risk of running a business if you can get the same return on a savings account? And so it appears that with negative interest rates corporations with zero profits can survive and that the economy doesn’t need to grow.

The road to inequality

Not so long ago an economist wrote a book that sent a shock-wave through the economic world because of stating a major cause of wealth inequality, which is that the return on capital usually is higher than the rate of economic growth. Capitalists reinvest most of their profits so capital usually grows faster than the economy most of the time. It can be proven beyond any doubt that capital can’t grow faster than the economy forever. Something will have to give at some point.

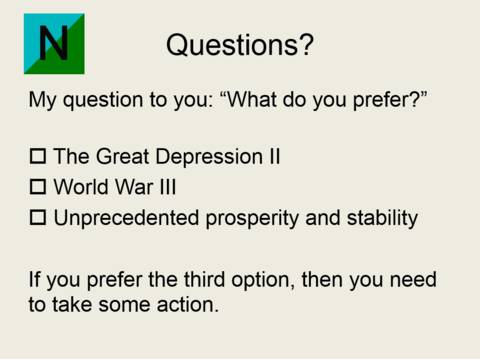

And what has this to do with interest? Interest is any return on capital. Interest income is the income of capitalists. That includes business profits and interest on bonds. The graph shows that labour income as part of the economy has diminished in recent decades in the United States. And that is because the capital share of national income has risen. In the past depressions and wars destroyed a lot of capital. Since 1945 there hasn’t been a serious depression or a world war.

The capitalist economy is like a game of monopoly. First everyone is doing great and capital is built in the form of housing and hotels. At some point some people can’t pay their bills anymore. To keep the game going, the winners can lend money to the losers. But at some point the losers can’t pay the interest any more. To keep the game going, interest rates must be lowered, so they can borrow more. But at some point some people can’t pay the interest again.

This happens in the real economy too. In a game of Monopoly we can start all over again. In the real economy that’s not an option. It would mean closing down factories in another great depression or destroying houses in another world war. So the game must continue. In Monopoly the rich can lend money at negative interest rates to the rest so that they can pay their bills. In the real economy this may be possible too.

Monopoly features a scheme that looks like a universal basic income. Every time you finish a round you get a fixed sum of money from the bank. At some point the bank may end up empty. The rich can then lend money to the bank at a negative interest rate to pay for it. It might seem a stupid thing to do because Monopoly is just a game. But the real economy is not. It may need an income guarantee for everyone financed by the rich.

An outline of the future economy

Can we have an economy that is humane and in harmony with nature? A few centuries ago no-one would have believed that we could live the way we do today and most people would have believed that it is more likely that unicorns do exist. If excess resource consuming consumption is to be curtailed, fewer options for consumers remain, for instance there may only be organic products, and supermarkets in the future might look a bit like those in former socialist Germany.

That may not be so bad. People in socialist Cuba live as long as people in the United States despite the United States spending more on healthcare than any other country in the world. Cubans eat no fast food so they live a healthier life style. And Cubans suffer less from a negative self image than people who are exposed to the advertisement industry. Advertisements aim to make us unhappy with ourselves and what we have in order to make us buy more products and services.

Like in former socialist Germany there isn’t much freedom in Cuba. If the government is to regulate the fat content in fast food or the sugar content in sodas then we lose our freedom to become obese. Alternatively, the government could even end our freedom to destroy life on this planet and kill our children. That may be oppression. But the alternative may be a collective suicide of humanity. Even though socialism failed we may have to pick the best parts out of it and integrate them into a market economy.

If the most resource consuming non-essential activities are to be axed, entire industries will be wiped out like in socialist Germany. One can think of making air travel sustainable and what that will with ticket prices. It is bad for economic growth. Many people would not like this. Still, life in a future sustainable market economy can be much more agreeable than life in Cuba or former socialist Germany.

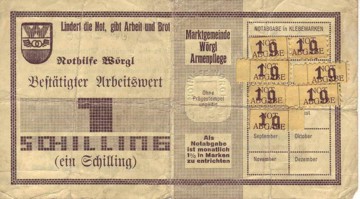

So what has this to do with interest? A dramatic change to make the economy sustainable can cause a massive economic shock like the Great Depression. The economy can soon recover if interest rates can go negative. Before you say that it is more likely that unicorns exist, this has been tested during the Great Depression. The outcome is dubbed the Miracle of Wörgl. And evidence for the existence of unicorns has not yet been so forthcoming.

If interest rates are low then the creators of ideas and makers of things are rewarded more. They are the entrepreneurs and labourers rather than the owners of capital. It is in the spirit of Silvio Gesell who believed that labour and creativity should be rewarded and not the passive ownership of capital. Only when there is a shortage of capital or more demand for goods and services than there is supply, people need to be encouraged to save.

The economy is already constrained by a lack of demand rather than supply. That will be even more so when excessive consumption is to be curtailed and the rich have fewer options to spend their money on. And so it may become possible to fund an income guarantee with income taxes as well as negative interest on government debt. This can improve the bargaining position of labourers.

It is better to have an income guarantee rather than a universal basic income because that would be cheaper. There is little to gain from handing out money to people that already have enough. And the scheme should provide an incentive to work. A simple example can explain how that might work out. Assume there is an income guarantee of € 800 per month and a 50% income tax. The following table shows the consequences for different income groups.

Perhaps it doesn’t feel right that people are being paid for doing nothing. But nowadays people are paid for producing and selling things we do not really need and by doing so they endanger our future. Someone who does nothing at all can be worth much more for society than a travelling salesperson, a trader on Wall Street or a constructor who builds mansions for the rich. Of course it is better that people do something useful and useful people should be rewarded for their efforts, but doing nothing is always better than doing something stupid, and having zero value is always better than having negative value.

Another question is how this can be paid for? The Miracle of Wörgl shows us that the economy can flourish without growth when interest rates are negative so that most people will be employed. Money can still be a motivator to run a business or to go to work but less so than in the present. It doesn’t have to stop people from starting a business. Many entrepreneurs didn’t intend to become rich. They just wanted to be an entrepreneur or believed in the product they were making or selling. Still, there is no doubt whatsoever that a humane economy in harmony with nature will be very different from the economy of today.

Featured image: Slums built on swamp land near a garbage dump in East Cipinang, Jakarta Indonesia. Jonathan McIntosh (2004).

Other images: Share of Labour Compensation in GDP at Current National Prices for United States. FED. Public Domain