The limitations of one-dimensional thinking

The Hegelian dialectic is about argument, counterargument and resolution. It locks us up in thinking along a one-dimensional line with two opposites. Perhaps the best solution is outside that line. The debate about capitalism versus socialism dragged on for over a century and has dominated world politics. But markets and states can’t create agreeable societies on their own. Much of politics is theatre rather than reasoning and solving questions. We often think of good versus evil rather than the advantages and disadvantages of alternatives. We might find better solutions if we can meaningfully model humans and their interactions.

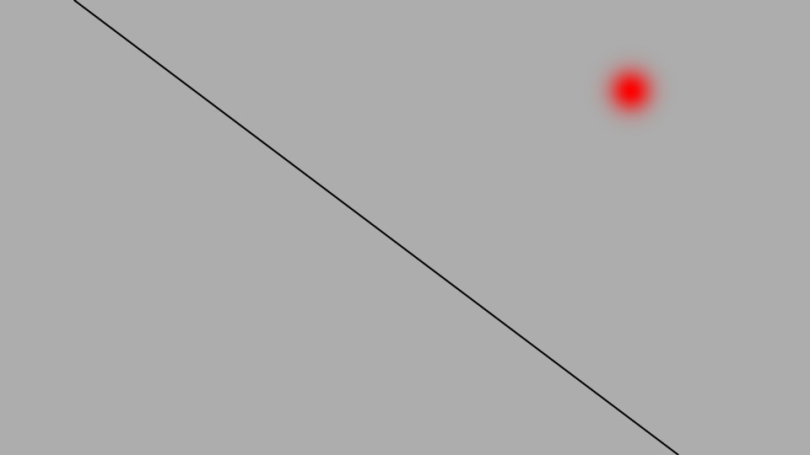

The limitations of thinking along a line like capitalism versus socialism become clear once you represent a line in a field. Suppose the grey area reflects the possible solutions, and the red dot is the optimal solution. If you reason along the black line, you only consider solutions on that line. If you design solutions by only thinking about how free markets should be and how much government interference we need, you might never consider the prevailing values in society. Your reasoning ignores human values. Thinking that markets and governments can solve society’s ailments is simplistic.

A line has one dimension. A plane has two dimensions, like the freedom of markets and shared values in society. You can represent three variables in a cube. For instance, you may add the state of technology as an additional variable. You won’t find the best solution if you think along a plane inside a cube. The number of variables can be higher. Freedom of markets and values in society are vague notions you can break down into dozens of more concrete variables. And if you have variables, you need ample data to estimate their impact. That data can be inconclusive. How do you know some other variable you didn’t think of didn’t interfere with the outcome? Despite all the models they used, central banks didn’t foresee the 2008 financial crisis. So yes, models can be wrong.

Still, models can be helpful. Our minds have constraints. We often take a perspective and reason from there. A socialist economist might tell us why capitalism fails but not what is wrong with socialism. There are economic theories that explain specific phenomena under certain conditions. And you might find additional answers in psychology, sociology, or even history. You might want to know what is wrong with your ideas before trying. You can run the idea through those theories. And that might give new insights. You can’t be sure you are right, but you can eliminate errors using models.

Natural Money is a research into an interest-free financial system. It draws from economic theories, monetary economics, banking, psychology and even history. I reviewed that idea with the help of existing theories and historical evidence to investigate how it might work in practice. During the process, issues came to light that I hadn’t thought of. Once interest rates in Europe went below zero, a resistance against negative interest rates manifested. Savers are irrational and prefer 2% interest and 10% inflation over -2% and 0% inflation.

It suggests we measure our gains and losses in our currency rather than purchasing power. And behavioural economics says we give more weight to losses than gains. The 4% loss in interest income impresses us more than the 10% reduction in inflation. These irrational emotions are human nature. It seemed pointless to try to convince savers that they were better off. Once I realised that, I could look for a fix for this awkward human feature by making negative interest rates appear as inflation.

The insights models give

Economic theories are models. Models are simplifications or abstractions. They can be loose and without numbers, like raising interest rates leads to lower economic activity. They can go into detail and include mathematics and predict that raising interest rates by 1% will slow economic growth by 0.5%. Models have limitations. Reality is much more complex than we can comprehend, so a model’s predictions are often off the mark. Still, models require us to use logic to establish which ideas might work under what circumstances by analysing an issue from different perspectives.

Proverbs can disagree with each other. Two heads are better than one, but too many cooks spoil the broth. And he who hesitates is lost while a stitch in time saves nine. Contradictory statements can’t be simultaneously correct, but both can be correct in different situations or times. Hence, we want to know which advice is best in which situation or what combination works best.

Models usually are better than uneducated guesses, and using a combination of models can lead to better outcomes than using a single model. That is why weather forecasters use up to fifty models to make a weather prediction. People who use a single model do poorly at predicting. They may be correct occasionally, just like a clock that has stopped is sometimes accurate, and endlessly tout their few successes while forgetting about their endless list of failures. These people will never learn anything from experience.

Intelligent people use several models and their judgement to determine which models best apply to the situation. Only people using multiple models together make better predictions than mere guessing, but they can be wrong. Models help us think more logically about how the world works and eliminate errors we would make otherwise. They can also give us insights into phenomena we wouldn’t get otherwise. To illustrate that, we can use models to investigate why people of the same ethnicity often live together and why revolutions are difficult to predict.

Sorting and peer effects

Groups of people who hang out together tend to look alike, think alike and act alike. If you look at the map of Detroit, you see people of the same ethnicity living together. Blue dots represent blacks, and red dots represent whites. We can’t change our skin colour, so if we hang around with people who look like us, that is sorting. We also adapt our behaviour to match that of others around us. When you hang around with smokers, you may start smoking too. Alternatively, if you hang out with people that don’t smoke, you might quit smoking. That is the peer effect. Both sorting and peer effects create groups of similar people who hang out with each other. Models can help us understand how these processes work. The phenomena seem straightforward, but we can model them.1

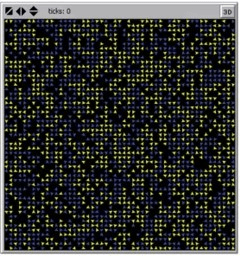

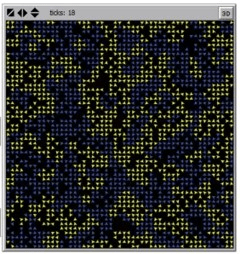

Schelling’s segregation model gives a possible explanation for how segregation works. Schelling made a model with individuals following simple rules. Suppose everyone lives in a block with eight neighbours. Red boxes represent homes where rich people live, and grey boxes are homes where poor people dwell. The blank box is an empty home. Assume now that everyone has a threshold of similar people who will make them stay.

A rich person might stay as long as at least 30% of his neighbours are rich. Assume a rich person lives at X. In this case, three out of seven or 43% of the neighbours are rich, like the person living at X. If one of the wealthy neighbours moves out, and a poor person takes that place, 29% of the neighbours will be rich, and the person living at X will move.

You can use a computer to simulate how that works out over time. Assume there are 2,000 people; 1,000 are poor, represented by yellow dots, and 1,000 are rich, represented by blue dots. Suppose they are distributed randomly at the start, and everyone wants to live amongst at least 30% similar people. In that case, the average is 50% alike, and only 16% are unhappy because less than 30% of their neighbours are alike. As a result, people start to move, and you will end up with a situation where the average is 72% similar and 0% unhappy.

Even when everyone likes to live in a diverse neighbourhood where only 30% of their neighbours are like them, segregation occurs. Segregation may not be the intention of the individuals involved, as they might be tolerant people requiring only a minority of similar people living in their neighbourhood.1 Whether that is the case is a different question. But if it is so, and if we believe segregation is undesirable, managing the ethnic makeup of neighbourhoods makes sense.

Peer effects cause people to act alike. Contagious phenomena are peer effects. They often start suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere. In uprisings and revolutions, extremists frequently determine what happens, for example, with uprisings such as the French, Bolshevik and Maidan revolutions. In hindsight, several pundits saw it coming, but things could have proceeded differently. It is difficult to predict revolutions. Granovettor’s model gives a possible explanation as to why that is so.

Suppose there is a group of individuals. Each individual has a threshold for participating in an event like an uprising and will join if at least a specific number of others join. If your threshold is 0, you do it anyway. If your threshold is 50, you start if you see 50 participants. The outcome varies depending on the thresholds of other people that might get involved.

Suppose there are five individuals, and the behaviour is wearing a suit. One individual has a threshold of 0, one has a threshold of 1, and three have a threshold of 2. The following will happen: one individual starts wearing a suit because her threshold is 0. The second individual joins because his threshold is 1. Then, the three remaining individuals join in because their threshold is 2.

If the thresholds had been 1, 1, 1, 2, 2, nobody would have worn a suit despite the group, on average, being more open to the idea. If the thresholds had been 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, everyone would have worn a suit after five turns, even though the group, on average, was less keen on doing this. In this case, extremist suit-wearers determine the outcome.

It indicates collective action is more likely to happen with lower thresholds and more variation. The influence of variation is surprising. It might explain why it is challenging to predict whether or not something like an uprising will happen. Not only do you need to know the average level of discontent, but you must also see the spread of discontent among the population and connections between individuals and groups.1

The proof is in the pudding

Do similar people hang out together because of sorting or the peer effect? That is the identification problem. Sometimes, it is clear. Segregation by race occurs due to sorting. Other situations are less clear. Often, you can’t tell whether it is sorting or peer effect because the outcomes are the same. Happy people hang out with each other, as do unhappy people. Both sorting and peer effects may have caused this.1

Models provide new insights, like why similar people hang out together and why revolutions are difficult to predict. Other models help us investigate what might happen under which circumstances. Thus, models explore the dimensions of complex questions and help us identify the spots where the best solutions dwell. In this way, models can assist us. For instance, if we intend to make everyone contribute to a good cause, we might want to model humans to see how we can do that. But not everyone is the same.

If we see humans as rational beings with good intent, we can convince them with arguments to do the right thing. If we see humans as religious creatures, an inspiring story can make them do it. If we think humans are calculating individuals, incentives and punishments can make them do the right thing. If we see humans as status seekers driven by pride seeking recognition, we might achieve the objective by telling them how great they are. You may get the best result if you use a combined approach.

Model or myth?

You can look at a model in several ways. How well does it explain the facts? How well does the model predict future events? Is the model correct? Is the model useful for a purpose? All models come with limits. They can be simplifications that explain a particular selection of events or predict specific future events. We also have worldviews that are our models of reality. We are creative thinkers and connect the dots in different ways. Our worldviews might be fiction mixed with facts. But a model doesn’t need to be correct to be helpful. Worse, irrational beliefs might save you. Believing is about surviving, not about being right. That is why humans are religious creatures. An example can illustrate that.

The replacement theory alleges that the elites aim to replace white populations with non-whites through mass migration and lowering the birth rate of whites. That can ‘explain’ mass migration and lowering birth rates of whites, and also pro-life activists trying to ban abortion because the abortion rates of whites are lower than those of non-whites. You might even believe there is a sinister anti-white force operating behind the pro-life movement, probably Jews. It explains the facts neatly as long as you ignore evidence to the contrary. The theory is so flimsy that it is hard to believe that rational, intelligent people would think it is correct. Only the rationality of a belief is not in its correctness.

Had the Native Americans believed from the onset that whites were an evil race with nefarious inclinations, not humans, but trolls from a dark place where the Sun never shines who were planning to murder them, so that they had to eliminate these pale abominations at all costs, they might have fared better in the centuries that followed. But there was no reason to believe that when the first starving whites washed ashore. You had to be crazy to think that. And if the natives had eliminated the whites and prospered, critics might later have argued it had been unnecessarily cruel to genocide these pale faces. But in this case, an irrational belief might have saved them from disaster.

Most immigrants have no evil intent and seek a better future for themselves and their children. Business elites may need additional labour or aim for low wages. Immigration is a way to achieve that. Political elites may try to keep the peace by promoting diversity. Western countries signed humanitarian treaties to allow asylum seekers. In recent decades, policies in Europe and the United States aimed to limit immigration. However, immigration continues unabated and has led to a border crisis in the United States, and the theory gives a so-called explanation.

Renaud Camus is the intellectual father of the modern replacement theory. According to Camus, replacement comes from industrialisation, de-spiritualisation and de-culturisation. Materialistic society and globalism have created a replaceable human without national, ethnic, or cultural specificity. Camus argued that the great replacement does not need a definition, as it is not a concept but a phenomenon. Indeed, the predominant liberal ideology in the West is globalist and serves the interests of the capitalists. And if money becomes our primary measure of value, other values lose meaning.

Humans cooperate based on shared myths like religions and ideologies. The replacement theory is a shared myth. It helps bond the group members and prepare them for collective action. That might be limiting migration, sending back migrants, or even a race war. The myth needs not to be correct but helpful for its purpose. If you fear the consequences of mass migration or are living together with far-right people, it is rational to accept the myth. It can generate collective action or make you acceptable within the group.

Critics argue that the replacement theory can be an excuse for right-wing violence. In a similar vein, multiculturalism can be an excuse for left-wing violence. In both cases, there are examples, and the perpetrators often have mental health issues. In 2002, a left-wing extremist assassinated a Dutch anti-immigration politician after another had been permanently handicapped in a previous attack sixteen years earlier. In 2011, a Norwegian right-wing terrorist assassinated 77 people in a bid to prevent a ‘European cultural suicide’. Most of them were whites.

Modern multiculturalism is also a myth. Multicultural societies supposedly have people of different races, ethnicities, and nationalities living together in the same community. In multicultural communities, people retain, pass down, celebrate, and share their unique cultural ways of life, languages, art, traditions, and behaviours, or so we are told. In most cases, it is not a reality. Ethnic groups often live in separate quarters, and cultural differences can cause trouble. But the purpose of the myth is to keep the peace.

Once you accept a myth, it becomes a faith, and you start ignoring evidence to the contrary. That may be why progressives and conservatives drift apart on this issue. It is a survival mechanism. We can’t foresee the future. Maybe multicultural societies will disintegrate and descend into gang violence and civil war. Alternatively, multiculturalism may promote world peace. For both outcomes, plausible scenarios exist. Your future and that of your children are on the balance, so it is natural to have strong feelings about the matter and rally around a myth that can generate the collective action you think is needed.

Latest revision: 13 April 2024

Featured image: Line And Dot On A Grey Rectangle. The artist wishes to remain anonymous because who wants to be as famous as Piet Mondriaan?

1. Model Thinking. Scott Page. Coursera (2014). [link]