Is the financial sector overtaking the real economy?

Less than 1% of foreign exchange transactions are made for trading goods and services. More than 80% are made for exchange rate speculation. Every three days an entire year’s worth of the European Union’s GDP of € 13 trillion is traded in the foreign exchange markets.1 So is the financial sector overtaking the real economy?

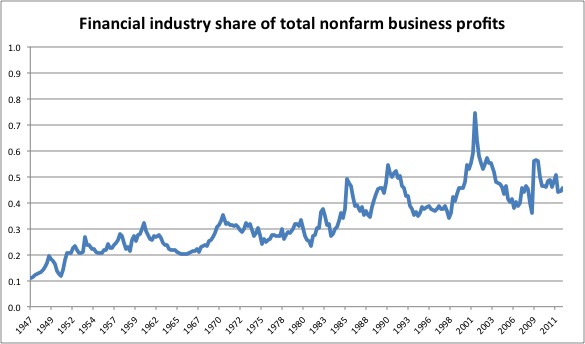

In the United States financial sector profits grew from 10% of total non-farm business profits in 1947 to 50% in 2010.2 This figure excludes bonuses. It is explosive stuff and the original research has been removed from the Internet. The findings could give us the impression that the financial sector is a big fat parasite that feeds on us. And who would have guessed that?

What a scary monster the financial system has become. This terrible creature could easily wipe out human civilisation as we know it. That nearly happened in 2008. And it can still happen. We are hostage of this monster. It is too big to fail. But what created it? It wasn’t Frankenstein for sure. The answer is already out there for thousands of years. It is interest on money and loans. In the past this was called usury and often forbidden.

The core problem is that incomes fluctuate while interest payments are fixed. This causes instability in the financial system. And if the investment is more risky, lenders demand a higher interest rate, which contributes to the risk. Limiting interest would reduce leverage and make financial system more stable and less prone to crisis.

It’s the usury, stupid!

Fraud in the financial sector contributed to the financial crisis of 2008. To what extent the fraud or the size of the financial sector are to blame is less clear. Financial crises are not a recent phenomenon. They have caused economic crises in the past. For instance, the stock market crash of 1929 and the subsequent bank failures caused the Great Depression of the 1930s. Back then the financial sector was not as large as it is today and there was no large-scale mortgage fraud. Hence, there must be another cause.

Charging fixed interest rates on debts causes problems as incomes fluctuate. So if some person’s income or some corporation’s profit suddenly drops, interest payments may not be met. When the economy slows down that happens to a lot of people and corporations simultaneously, which makes the financial system prone to crisis. And interest is a reward for risk. Creditors may be willing to lend money to people and corporations that are already deeply in debt, but only if they receive a higher interest rate. So if interest was forbidden, that might not happen, and there could be fewer financial crises.

Banning interest has been tried in the past and it failed time after time. That is because without interest lending and borrowing wouldn’t be possible and the economy would come to a standstill. Until now there was a shortage of money and capital so interest rates needed to be positive, but that may be about to change. The increased availability of money and capital pushed interest rates lower. Money and capital may soon be so abundant that interest rates can go negative. That could be the end of usury.

The scary monsters in the financial system

Apart from exchange rate speculation there are frightening creatures like quantitative easing, shadow banks and derivatives. These things will be explained later in this post. Some experts believe that the financial sector is out of control. That may not be the case. Usury created this monster so Natural Money, which is negative interest rates and a maximum interest rate of zero, could make many of these seemingly hard-to-solve issues disappear, and perhaps shrink financial sector profits too.

Leverage, shadow banking and derivatives make the financial sector so profitable for its operators because of interest and risk. Interest is a reward for risk but interest also increases risk because interest charges are fixed while incomes aren’t. But more risk means more profit for the usurers because all that risk needs to be ‘managed’. That provides opportunities to profit for those who make the deals. Usury is the main cause of financial crises and generates most financial sector profits.

Quantitative easing

Quantitative easing means that central banks print money to buy debt with this newly created money. Trillions of dollars and euros have been printed so central banks now own trillions in debt. In this way the financial crisis of 2008 was stemmed. Investors and banks wanted to get rid of debts and preferred cash because there was a risk that some of these debts would not be repaid in full. This caused the crisis.

But what if there was a tax of 10% per year on cash and central bank deposits? Losing a few percent on bad debts suddenly doesn’t seem such a bad deal any more. Investors may have kept these debts and the crisis would not have occurred. The losses on bad mortgages turned out to be a lot less than 10% per year. That was also because the crisis was halted with central bank actions like quantitative easing.

If there had been a tax on cash and central bank deposits there would always have been liquidity. The crisis may never have happened in the first place and quantitative easing may not have been needed. And if this tax is going to be implemented in the future, investors may gladly gobble up the debt on the balance sheets of central banks, so that quantitative easing can be undone, and most likely at a profit for the taxpayer.

Shadow banks

In order to protect depositors, banks are subject to regulations. Regulations are bad for profits because they limit the risks banks can take. Bankers who were looking for bigger bonuses came up with a scheme that is now called shadow banks. Shadow banks don’t offer deposit accounts to ordinary people so regulations don’t apply. And so shadow banks can take more risk and generate more profits.

A shadow bank borrows money from investors and invests it in products like mortgage-backed securities. A mortgage-backed security is a derivative that looks like a bunch of mortgages. The owner of the security doesn’t own the mortgages themselves, but is entitled to the interest from the mortgages but also the losses when home owners fall behind on their payments. Not owning the mortgages themselves makes trading a lot easier because mortgages involve a lot of paperwork.

Shadow banks can be dangerous because bank regulations don’t apply. Ordinary banks are required to have a certain amount of capital to cushion losses so that depositors can be paid out in full when some loans aren’t repaid. The balance sheet of an ordinary bank might look like the one below:

|

debit

|

credit

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

mortgages and loans

|

€ 70,000,000

|

deposits

|

€ 60,000,000

|

|

loans to other banks

|

€ 10,000,000

|

deposits from other banks

|

€ 20,000,000

|

|

cash, central bank deposits

|

€ 10,000,000

|

the bank’s net worth

|

€ 10,000,000

|

|

total

|

€ 90,000,000

|

total

|

€ 90,000,000

|

But shadow banks don’t need to comply to these regulations because they don’t have depositors. And so the balance sheet of a shadow bank might look like this:

|

debit

|

credit

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

|

mortgage-backed securities

|

€ 500,000,000

|

short-term lending in money markets

|

€ 490,000,000

|

|

insurance and credit lines

|

the shadow bank’s net worth | € 10,000,000 | |

| total |

€ 500,000,000

|

total | € 500,000,000 |

What is so great about shadow banking, at least for bankers? If banks borrow at 2% and lend at 4%, the ordinary bank can make € 1,400,000. The bank’s net worth is € 10,000,000 so the return on investment is 14%. But the shadow bank can make € 10,000,000 and the return on investment is 100%. And you can imagine how great this is for bonuses. Only, if something goes wrong, there is little capital to cushion losses. That’s not a problem for the bankers because by then they have already cashed their bonuses. But it could become our problem as shadow banks can blow up the financial system.

If the loans drop 10% in value because some home owners fall back on their mortgage payments, the capital of the ordinary bank can cushion the loss of € 8,000,000, while the shadow bank goes down in flames leaving an unpaid debt of € 40,000,000. And now we get to the point where financial system blew up. It is the insurance and credit lines part on the balance sheet of the shadow bank. There is no value attached because credit lines so insurances don’t show up on balance sheets or only for a very low amount.

Ordinary banks guaranteed credit to shadow banks just in the case investors like money market funds didn’t want to invest in shadow banks any more. The great thing of credit lines for bankers is that they get a fee for these credit lines while they don’t appear on the balance sheet so that banks don’t have to cut back their lending. When homeowners fell behind on their payments, investors didn’t want to invest in shadow banks any more, and these credit lines had to be used. This means that ordinary banks had to step in and suddenly their capital wasn’t sufficient to cover the losses. Also going down in flames, were the insurers of mortgage-backed securities.

The United States had a government policy of stimulating home ownership. Under the guise of this policy mortgages were given to people who couldn’t afford them. Behind the scenes usury was to blame. If there was doubt whether the borrower could afford the mortgage, a banker could charge a higher interest rate to compensate for the risk. This made the mortgage even less affordable to the borrower. The solution for that problem was giving ‘teaser rates’, meaning that the interest rate was low during the first year so that the home owner could afford the mortgage payments at first. Meanwhile the mortgage was packaged in a mortgage-backed security so the banker was already off the hook when the home owner fell behind on his or her payments.

And there is more. Shadow banks offer higher interest rates to their investors. Shadow banks don’t have a lot of capital so investing in them is a more risky than putting money in a bank account of a regular bank. Investors in shadow banks need a compensation for that risk. That’s no problem because the enterprise is very profitable. It is therefore possible for shadow banks to pay higher interest rates. This might not be possible if interest was forbidden, unless shadow banks had a lot more capital to cover their losses, but that would solve the problem of them being too risky. It is usury that allows for risky schemes like shadow banks to exist.

The multi-trillion-dollar derivatives monster

In 2016 the notational value of all outstanding derivatives is estimated to be $650 trillion. This is the so-called multi-trillion derivatives monster. This figure is more than eight times the total income of everyone in the world.3 Some people are spooked by the sheer size of that number. And indeed, derivatives can be dangerous. In 2003 the famous investor Warren Buffet called derivatives ‘financial weapons of mass destruction’.

Five years later derivatives played a major role in the financial crisis. An improper use of derivatives nearly brought down the world financial system. But derivatives can be useful. Most banks use derivatives to hedge their risks. Banks that managed their risks well using derivatives fared relatively well during the financial crisis compared to banks that didn’t.4 Therefore, derivatives are probably here to stay.

But what about the multi trillion monster? The number is a notational value, not a real value. Derivatives are insurance contracts, often against default of a corporation, a change in interest rates, or home owners falling behind on mortgage payments. You may have a fire insurance on your house to the amount of € 200,000. This is the notational value of the contract. You may pay the insurer € 200 per year. That is the real value of the contract, until something happens, that is.

If your house burns down, the contract suddenly is worth € 200,000. Insurers often re-insure their risks, which is a prudent practice. But re-insurance makes the notational value of the outstanding derivatives increase. So if your insurer re-insures half of your fire insurance to reduce its risk exposure, another contract with notational value of € 100,000 is added to the pile of existing insurance contracts.

So what went wrong? If suddenly half the houses in a nation catch fire because there is a war, insurers go bankrupt. The cause of the financial crisis was many home owners falling behind on their payments at the same time so that insurers of derivative contracts like mortgage-backed securities went bankrupt. The American International Group (AIG) was the largest insurer of these contracts and it was bailed out with $ 188 billion. The US government made a profit of $ 22 billion on this bailout, but only because the financial system wasn’t allowed to collapse.

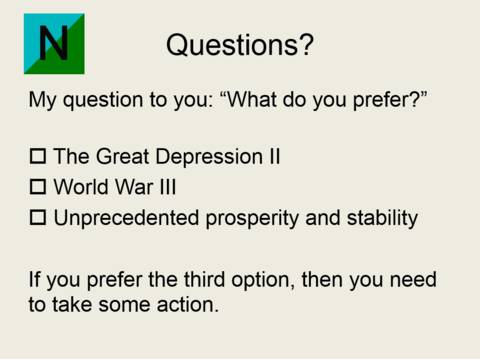

In a financial crisis a lot of things go wrong at the same time. The financial system can’t deal with a major crisis. If it happens, it may cause the greatest economic depression ever seen, and in retrospect it may herald the collapse of civilisation.

The usury issue

Money circulation in the economy is like blood circulating in the body. It makes no sense for a kidney or a lung to keep some blood just in case the blood stops circulation. The precautionary act makes the dreaded event happen. It is a self-fulfilling prophecy. A financial crisis is like all parts of the body scrambling for blood at the same time. When the blood circulation stops, a person dies. An if the money circulation stops, the economy dies. Hoarding is to blame for that.

Perhaps big banks are too big to fail. Breaking them up may not help because the banking system is closely integrated. Banks lend money to each other. If a few banks fail then others get into trouble too. And in a crisis all the trouble happens at the same time. So perhaps it is better to address the cause of failure itself, which is interest on money and debts. And it may be possible because interest rates are poised to go negative.

A tax on cash makes negative interest rates possible. It can also keep investors from hoarding money. If money keeps on circulating, there may never be a crisis. The crisis happened because investors scrambled for cash when they feared they might lose money on bad debts. But if they expect to lose more on cash, they might keep their debts. And there may have been fewer bad debts in the first place if there had been no interest on debts as interest is a reward for risk.

Featured image: Graffiti near the Renfe station of Vitoria-Gasteiz. Wikimedia Commons. Public Domain.

1. The rise of money trading has made our economy all mud and no brick. Alex Andreou (2013). The Guardian. [link]

2. The Rise of Finance. Evan Soltas (2013). Economics and Thought. [no link because the information has been removed]

3. Here’s What Makes the Derivatives “Monster” So Dangerous (for You). Michael E. Lewitt (2016). Money Morning. [link]

4. Financial innovation and bank behavior: Evidence from credit markets. Lars Norden, Consuelo Silva Buston and Wolf Wagner (2014). Tilburg University. [link]