Crossroads of civilisation

In several ways, the Netherlands has been ahead of the rest of the world, such as in liberal reforms like gay marriage and the right to decide about ending one’s own life. It was the result of the political manoeuvring of the left-wing liberal party D66 and, most notably, its leader, Hans van Mierlo, who had schemed to make it happen. The Christian Democrats, who had always been in the government, had long blocked progressive reforms. In 1994, after the Christian Democrats had lost the election, D66 forged the purple coalition with the social democrats of the PvdA and the right-wing liberals of the VVD. These parties set aside their differences and focused on their shared progressive values to implement amendments. A large section of the Christian Democrat electorate supported these changes, including most Roman Catholics, so they remained uncontested afterwards.

The Netherlands is one of the least nationalist countries. In their preparedness to die for their country, the Dutch score particularly low, according to a Reddit survey. It is the most closely tied to both the continental European and the Anglo-Saxon world. Together with Great Britain, the Netherlands is oriented toward the United States. It may explain why the Dutch provided more NATO heads than any other country. If geographical distance indicates cultural distance, it is worth noting that the Netherlands lies between Great Britain, Germany, and France. Being close to Scandinavia, it was also one of the least corrupt countries, with a fiscally prudent government.

The Netherlands long ranked highly in sexual liberty. Prostitution is legal and performed openly in red light districts. It was not all good. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, paedophiles could operate in the open until the focus returned to the damage they do to children. On the work floor, equality is the norm, as the Dutch balance work and private life, which is uncommon in most countries. In many ways, the Netherlands has progressed the furthest. The Netherlands doesn’t lead on all fronts. For example, the country lags in the number of women on boards and in parliament.

On top of that, the border between the Roman Catholic and Protestant worlds runs through the Netherlands. And so, it became the crossroads of Western civilisation, and with more minorities coming in, the crossroads of world civilisation. That wasn’t on my mind at the time, but in hindsight, there is more to it. The Netherlands means ‘the Low Countries’ because half of it lies below sea level. The word ‘Nederland’ almost translates to ‘humble country’. The most unpretentious part of it might be Twente, the region I came from.

The Dutch are known for their tolerance, which is close to indifference. There had long been parallel societies with Protestants, Catholics and socialists living separate lives, so it was mind your own business. For long, Protestantism had been the official religion and Catholicism was illegal, but Catholics could hold masses in secret. That was tolerance. Today, smoking weed is not a problem. The Netherlands was also a haven for Jews until the German occupation during World War II. That same tolerance was the stance towards immigrants for a long time. In that sense, the Netherlands didn’t differ from several other Western European countries.

It was a fairy-tale society, with Van Kooten and De Bie seeking the nuance. Their characters represented the so-called conservative, ignorant and xenophobic undercurrent in the Dutch culture, and of course, hustlers, such as Jacobse and Van Es, infiltrating politics with their corrupt schemes and dubious deals. The undercurrent didn’t go away. Instead, it grew stronger. Immigrants continued to arrive, causing a growing unease. The progressive values many Dutch cherished didn’t agree with the conservative worldview of many immigrants, most notably Muslims. These feelings only needed a catalyst, like the Germans needed Hitler, to give the anger and discontent a voice.

The existing political parties had become complacent and didn’t see what was coming. Nor had I. After the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, a maverick politician, Pim Fortuyn, rose to prominence with his strong views on immigration and Islam. Fortuyn claimed that leftists were to blame for immigration. He called them the Leftist Church for their moral superiority claims. They would call you a racist if you opposed immigration. Many wanted to contain immigration, most notably of groups that had trouble adapting. Only, no politician said it that plainly as Fortuyn did. The others were more careful not to promote division in society. Most immigrants did okay, and inciting hatred wouldn’t improve things. Keeping a good society is not a simple affair. It is like a juggling act of keeping many balls in the air. Fortuyn didn’t seem to understand or care and sought personal fame.

Balls on the ground

Fortuyn had terminated the fairy tale of the multicultural society. I had believed in it or wanted to believe in it, for if there will ever be world peace, the world must unite and become one multicultural society. Living with people from different cultures isn’t easy. I should have known that, given what happened to me as a student. Culture can be an unbridgeable gap. Some Fortuyn supporters seemed to anticipate civil war and hoped that it would start sooner rather than later, when the authentic white Dutch were still a majority. The atmosphere quickly turned grim. Under the guise of free speech, the sewers opened, and the rivers of hatred flooded freely into the open. Fortuyn’s rise made headlines in the international press because it represented a clear break with the past, occurring in what many believed was the most liberal country in the world.

Fortuyn supporters overran the IEX message board with their vile and racist comments. So when someone created a new account on IEX, started posting, while suggesting he was a Turk to test the mood, others viciously attacked him. Fortuyn was openly gay, and his objection to Islam was that it didn’t agree with Western liberal values. He further pointed out crimes committed by immigrant youth, especially those of Moroccan descent. Racists and bigots jumped on his bandwagon. However, and that was where leftists like me got it wrong, the movement was more than just bigotry and racism. Tribal identities are obstacles to unity, not only internationally, but also within countries. It is as problematic as the existence of nation-states. Fortuyn picked up one ball while dropping several others.

A leftist poster with the avatar Kingie started a new website, BeursKings (MarketKings), with the help of. Danger Money. A small group left IEX and joined the new message board. I was among them. I was part of the so-called Leftist Church and had tried to rein in the onslaught of bigotry. One of the IEX posters called me ‘vicar’ for my efforts to moralise. Had BeursKings not started, I would have remained on IEX, so it was not a case of fleeing. BeursKings remained in operation for several years. Kingie once posted several photographs of himself on the website. That was a shock. He looked like my double. In hindsight, that is remarkable because of his avatar name. Others who remained on IEX also joined the BeursKings message board.

Shortly before the elections, a left-wing loner assassinated Fortuyn. Fortuyn had already hinted at it. If something were to happen to him, he claimed, it would be because establishment politicians had demonised him. The socialist-in-name-only Marcel van Dam, who lived in a luxurious mansion far away from multicultural neighbourhoods, and who had always been eager to take the moral high ground, once called Fortuyn an ‘exceptionally inferior human.’ And so, you may ask yourself, who of the two was the most superb Nazi? Fortuyn gave a presentable at-your-service salute that might do well in some fascist circles, but his ‘inferior human’ remark gave Van Dam the edge.

Others called Fortuyn ‘extreme’ or ‘demolishing society’ because he was stirring up public sentiment. Fortuyn was a man of theatre, hyping the wrongs others did to him while being a jerk himself. The Netherlands is not a violent country. It was the first political assassination in 400 years, so no one saw it coming. The civil war didn’t arrive, but death threats to politicians have become common. The attitudes toward immigrants and Islam have also changed. Fifteen years later, the United States saw the rise of a similar leader.

Fortuyn’s assassin, Volkert van der Graaf, was diagnosed with Asperger’s syndrome. He was someone like me. To him, Fortuyn may have been a new Hitler on the rise. He feared Fortuyn would tear down Dutch society so that the weak, such as the poor and refugees, would suffer, and also animals, as he had been an animal rights activist. Van der Graaf drew a logical conclusion from the facts, or so he believed. The problem with this kind of thinking is that we don’t know the future. Mass immigration can destabilise a country. Van der Graaf had good intentions, but Fortuyn also believed he was serving the Netherlands. Yet, there was something evil about Fortuyn. I am not a trained psychologist, but Fortuyn was someone who wanted to be the centre of attention and wield power, and didn’t care about the consequences of his actions, much like Donald Trump.

Harry Mens, a Dutch real estate tycoon whom you might call the Dutch Donald Trump, had promoted Fortuyn on his television show, Business Class. So, like Trump, Mens had a television show. Fortuyn’s appearance on his show foreshadowed a new type of politics, common in the United States but not in the Netherlands, in which wealthy money men run puppet politicians. I found Mr Mens to be a questionable character, boasting and flaunting his wealth. At the time, I didn’t think of Trump, but there are parallels. His programme was about investments with people in suits and dresses promoting their investment services. A few advertisers on his show turned out to be frauds, such as Palm Invest.

I think of Pim Fortuyn and Donald Trump as narcissistic psychopaths. These are not official diagnoses, but personal impressions. However, some psychoanalysts concluded that Fortuyn was a narcissist, possibly because of feelings of inferiority that he needed to compensate for with praise. It was all about him, and other people were just utensils. His neurotic disturbances and unresolved personality flaws made Pim Fortuyn such a powerful force. One psychoanalyst said, ‘Imagine if he had to go on a state visit to US President Bush. He would exhibit Sun King-like behaviour.’1 To Fortuyn, the US President would have been a mere extra in the Pim Fortuyn show. Even though the psychoanalysts didn’t raise that particular issue, Pim Fortuyn seemed to enjoy hurting other people’s feelings, so I suppose he was a psychopath as well.

If you consider the characteristics of narcissistic psychopaths, you might discover they are the opposite of Asperger’s syndrome. I name a few: (1) thriving on chaos versus thriving in order, (2) desiring to be the centre of attention versus not wanting attention or praise, (3) manipulative and lying versus honest and forthright and (4) charming versus impolite. At first glance, Fortuyn and Trump seemed impolite rather than charming. That needs further explanation. First, you don’t have to check all the boxes to be autistic or a psychopath. And second, the impoliteness of the autistic person comes from being honest. By being rude, Fortuyn and Trump catered to the fear and anger of their supporters. They told them what they wanted to hear. What can make psychopaths successful as leaders is that they are willing to hurt people, which may be required to do what is necessary. With these words, I conclude my psychoanalysis session.

Life went on

Beurkings attracted a few posters who remained on IEX. One of them, Xzorro, didn’t believe the 9/11 conspiracy theories and thought that the success of the attacks was due to the incompetence of the American authorities. Yet, he believed the allegations that a high-ranking Dutch Prosecution official, Joris Demmink, had had sex with underage male prostitutes and that there was a conspiracy within the Dutch government to cover it up. An investigative journalist and conspiracy theorist, Micha Kat, had pursued the matter relentlessly for many years. In the 1990s, there had been a police investigation into possible child abuse by four high-ranking government officials.

The investigation had collapsed after someone had leaked information. During raids, the police found no evidence on the suspects. Fred Teeven, who had led the investigation, later stated that Demmink had not been a person of interest. The Dutch newspaper AD claimed that Demmink had contact in the 1980s with a pimp of underage boys. Kat was onto something, but he was a nutter. Kat later claimed that children buried in a Bodegraven cemetery were the victims of Satanic child abusers, which was nonsense and easy to disprove. And Kat had a conviction for making death threats to a fellow journalist.

Another poster on BeursKings, Gung Ho, who lived in the Dutch countryside, favoured traditional US conservatism and posted lengthy pieces copied from American websites, some about US Neoconservatives being Leninist agitators. He enthusiastically promoted a penny stock, Clifton Mining, and believed that colloidal silver was a cure against many diseases. That made him the subject of mockery, most notably by Amoricano, an American of Dutch origin who long had been on IEX. Gung Ho might have been in the military and had friends in the American military, or so his sparse remarks about his personal life suggested.

Gung Ho regularly posted comments about the Neoconservatives being chicken hawks, so cowards who send others to war while having done no military service themselves. His use of language was odd. He didn’t express himself as most people would. That made his lengthy texts amusing. The connection between Neoconservatism and Leninism seemed obscure. Like the Leninists, the Neoconservatives use Hegel’s dialectic to promote social progress via revolutions and wars. The conflict between the West and Islam was their latest project, founded on the clash-of-civilisations ideology, and the Iraq War was one of its consequences. Traditional conservatives like Gung Ho opposed these methods. Fortuyn adhered to the neoconservative clash-of-civilisations ideology as well.

There was also a psychiatrist on BeursKings. He had quit his job and tried to make a living by day trading. He posted under the name Kindval, a soccer player from the 1970s. He didn’t seem to like me. When someone attacked me personally or for my political views, he upvoted these comments. The day trading probably didn’t go well. Once, Gung Ho went loose on him by suggesting he had psychological issues. I upvoted that comment. It was a rare occasion for me to upvote a negative comment. Kindval became agitated about Gung Ho’s comment, but even more about my upvote. It made me think that he was, as Gung Ho implied, on his way to a nervous breakdown.

No gain without pain

Fortuyn’s rise had made me curious about the troubles in the multicultural society. The fallout of my student years of not fitting in had made me interested in cultural differences. My view was that the multicultural society had to work because you can’t go back to nation-states. They are a thing of the past. So, what stands in the way of success? Is there really an unbridgeable gap between Islamic and Western culture? It made me interested in Muslims and what they were thinking. In 2004, I joined the message board Maroc.nl for people with a Moroccan background. They are a disregarded minority and face discrimination. Most notably, young Moroccan men are a source of trouble. There are other minorities with similar issues, but somehow Moroccans get most of the attention. They have a serious likability problem.

So, when the nationalist politician Geert Wilders singled out one particular minority for deportation, he took the Moroccans in his infamous ‘fewer Moroccans’ quote, ‘Fewer Moroccans. Let us take care of that.’ The Dutch dislike Moroccans more than other minorities. As the most-hated child of the entire school, I have been there. It was not entirely my fault, but I was part of the problem. Many Moroccans would probably agree, but they are not the ones who cause trouble. The issues Moroccans in the Netherlands face, and how they see themselves and relate to society, compare to those of blacks in the United States. The message board was open. Everyone could join. It featured discussions about religion and social issues. Various people shared their opinions and discussed them with one another.

People came and went on the message board over the years. Occasionally, there were heated exchanges, with Moroccans complaining about the racism of the Dutch and the Dutch complaining about the misconduct of the Moroccans. There were a few agitators on both sides. But overall, the discussions were meaningful and insightful. That was probably because of the diversity of the posters. I suspect the message board had received a grant and was obliged to keep it open to a variety of opinions. There were Christians, Jews, Muslims, former Fortuyn supporters, and leftists.

There were also a few gays seeking to counter the hatred of LGBTQ people among Muslims because of street violence against LGBTQ people in areas where Moroccans lived. There was a diversity of opinions and an exchange of views. People argue over who is right and who is wrong. I didn’t need to have my own opinion to learn from others. I didn’t have strong views. I was more interested in the problem itself. I could watch others dispute and consider the merits of their opinions.

Traditional Muslims are strict on religion, much like conservative Christians. They have more in common with each other than with liberals. So, why many liberals like Muslims, and conservative Christians dislike them, is quite an enigma if you reason from their perspectives on life. Terrorists usually are young men high on testosterone who seek meaning in life and find it in Islam, and then fall prey to extremist preachers. There aren’t that many of them, but a few hundred can already become a serious threat. During my first year, there was uproar over the Dutch publicist Theo van Gogh, who was indeed kin to the famous Dutch painter. Under the guise of freedom of speech, he called Muslims ‘goat fuckers’ and Muhammad ‘a pimp’. The people on the message board didn’t care much about being called ‘goat fuckers,’ but insulting Muhammad was a red line that genuinely upset them.

Several posters also expressed fury about the Somali lady Ayaan Hirsi Ali, who had left Islam for a liberal lifestyle, and had, together with Van Gogh, made the short film Submission about the suppression and mistreatment of women by Muslims. To Muslims, the film was blasphemous as it showed the bodies of abused women with Quran verses on them that the filmmakers claimed Muslims use to justify mistreating women. Hirsi Ali also had called Muhammad a ‘pervert’ and a ‘paedophile.’ She faced death threats. The anti-immigration and anti-Islam politician Geert Wilders also faced death threats and requires security to this day.

Hirsi Ali had escaped an arranged marriage. The Dutch police prevented her family from abducting her from an asylum seeker centre in Almelo. She later moved to the United States to work for the neoconservative think tank. Van Gogh paid for his Islam-insulting binge with his life. A youngster of Moroccan descent slit his throat, precisely 911 days after the Fortuyn assassination. That was on 2 November, which refers to the European emergency services telephone number 112, the European equivalent of 911. So, in the first year, the atmosphere on the message board was tense, perhaps explosive even.

Western interventions in the Middle East and Western support for Israel also angered people. Israel illegally occupied Palestinian land, and Palestinians kept on committing acts of terrorism. It has proven to be an unresolvable conflict due to violent extremists on both sides. Several posters on the message board viewed the West, including the Netherlands, as anti-Islamic. As I tried not to offend people with my opinions, I had positive karma on the message board. At first, I was making up my mind anyhow. It is a conflict between two worldviews with their own logic. There is an underlying truth, whatever that may be. In the first years, the American gangster heist called the Iraq War was still in progress. For me, the Iraq War became an unexpected mental dip. The Americans had tricked me into believing that Saddam Hussein had a stash of WMDs.

Once I saw live on CNN how the bombs fell on Baghdad and how gung-ho Americans invaded the country and murdered the defenceless Iraqis, my mood suddenly swung to dim. And then there were no WMDs. They had bombed a country into ruins and killed thousands for no good reason. Mission accomplished. Once again, Americans had confirmed the prejudice of being the trigger-happy cowboys who love their guns and shoot people for minor infringements like trespassing. And Iraq wasn’t even theirs. In the Wild West, it is the law of the gun, not the rule of law, that prevails.

The Netherlands has been a major contributor to the American war effort in Iraq as well as Afghanistan. The Dutch Prime Minister Balkenende had praised the Dutch VOC mentality of the former Dutch colonial enterprise that had invaded and looted the Indies under the guise of trade. The United States had merely copied that proud Dutch tradition of the looting oligarchic merchant republic of the Netherlands. The United States now has the VOC mentality. Shell was a Dutch company, so the Dutch had to be in on the action, or so Mr Balkenende may have reasoned.

Meanwhile, the American government told Americans it was their patriotic duty to purchase more planet-ruining gas-guzzling SUVs to make the scheme profitable. And of course, Americans are very patriotic when it comes to their excessive consumption. You can view the US dollar-based global economy as a scam that primarily benefits wealthy Americans. The whole world is subsidising their lavish lifestyles with their labour and resources. Western countries, including the Netherlands, benefited from this arrangement, as the American military provided peace and stability in Europe. But the world paid the Americans for it by using the US dollar as a reserve currency. The Americans were the leeches on the world’s dime, and they had the military to extort tribute.

That, and the liberal values, are reasons several posters found the West evil and hard to accept Dutch society. They may have used it as an excuse for their misconduct and crimes that they would have committed anyway. Some could easily get angry at you simply for being Dutch. Some Dutch came to the message board only to lecture the Moroccans about the backwardness of Islam or the misconduct of Moroccan youngsters. That didn’t work out so well. You wouldn’t change your mind when someone you have never seen before came out of the blue to tell you how stupid your religion is and that your community is a bunch of criminals. There was also a private messaging system. Over the years, two ladies contacted me as they preferred a Dutch husband and hoped that I was a Muslim.

Several posters wrote that they had been in prison. One of them posted from jail, so there was Internet there, or he had a smartphone. There definitely is a problem. It doesn’t mean that most Moroccans are criminals, but if the crime levels in their community, as the statistics suggest, are three times as high as among native Dutch, their community is a source of trouble. They would argue that you bear no blame for other people’s faults. Only that reasoning is a dead end. If your group’s culture includes values that contribute to these issues, it becomes a problem your community faces. There may be obstacles such as rejection and racism from the Dutch, but positive change begins with you. The West has its own issues to face, most notably the ethics of the merchant, which Balkenende proudly referred to as the ‘VOC mentality,’ so invading countries and robbing them under the guise of trade. We can only move forward if we deal with these issues.

The multicultural troubles weren’t constantly on my mind, but I couldn’t let the issue go. I remained on the Maroc.nl message board for two decades. In 2024, after more than twenty years, shortly after the Gaza War had started, the message board went offline permanently after being filled with anti-Israel messages. That was very suspicious indeed if you believe that the Jews are running this world. Jewish interest groups might have pulled some strings. By then, I had seen too many coincidences to believe that without evidence. And I had arrived at some conclusions. People aren’t willing to change. There will be no gain without pain, which I had already experienced firsthand as a student.

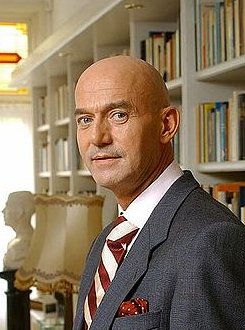

Featured image: Pim Fortuyn on 4 May 2002, two days before his assassination. Roy Beusker (2002). CC BY 3.0. Wikimedia Commons.

1. Een heel vervelend geval. Joris van Casteren (2002). Groene Amsterdammer.