Economic cycles

Mismatches between supply and demand cause economic cycles. A harvest may fail, and food prices may rise, leaving us with less money to spend on other items. Mismatches can concern the supply and demand of money, capital, labour, raw materials or consumer products. Interest charges also contribute to economic cycles. Interest rates reflect the market for funds. If all markets were perfect, economists argue, supply could adapt to demand instantly, and there would be no economic cycles. Not unlike many others, economists love fairy tales about a Paradise where everything is perfect. And so, they may advise us to make markets perfect, so that an economic Paradise will ensue.

Economic cycles occur because mismatches between supply and demand emerge periodically and eventually resolve. Economists use the term equilibrium in their models to explain the relationship between supply, demand, and price, but these models are simplifications of reality. There is rarely a stable equilibrium, and fluctuations in demand and supply cause changes in prices, inventories, and employment. There are several theories and explanations regarding those mismatches, economic cycles, and their effects. Most notably, money, credit and interest deserve attention.

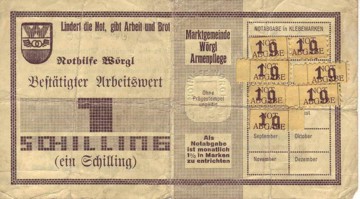

According to Say’s law, supply creates its own demand because we make goods and services to use ourselves or to acquire other goods and services. It is most applicable to a simple barter economy. When money serves as a medium of exchange, we can postpone our purchases, leaving producers with excess inventory. Money hoarding can be a serious problem as it interrupts the circular flow of money. When money loses value, we are less likely to postpone purchases. It is why central banks aim for a bit of inflation. However, inflation shouldn’t be too high, as that can undermine trust in the currency.

Expectations are another factor. When consumers feel good about the future, they are more willing to spend on big-ticket items. Likewise, when investors expect brighter prospects, they anticipate higher profits, making them more willing to invest. Conversely, when consumers and investors are pessimistic, the opposite happens. And so, expectations can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. Likewise, when people expect a bank to collapse, it may collapse because that expectation triggers a bank run. Policy makers try to instil confidence in the system because a lack of confidence can break it. The reason is that credit means trust, and trust is what keeps the system going.

During good times, businesses and individuals tend to be confident. Credit is often available because businesses’ and individuals’ future income projections serve as the basis for banks to lend money. And so, companies and individuals can borrow more in good times. When the economy slows and their incomes decrease, they may struggle to make their interest payments. Consumers would have more disposable income without debt, since they wouldn’t have to pay interest. Similarly, businesses can go bankrupt even when they are profitable overall because of interest charges. And so, interest charges can exacerbate and prolong the bust.

Leverage contributes to the overall risk in financial markets. Liquid financial markets make it easier to enter and exit positions, leading investors to believe it is safe to operate with leverage. If markets were not fluid, leverage would appear more dangerous, as it would be more difficult to exit a position. For example, if you aren’t sure that you can renew your mortgage after five years, you aren’t going to buy a home. Liquidity enables risk-taking, allowing the overall level of risk in the financial system to increase. That can become apparent during a crisis. People who have to sell their home during a housing crisis may end up selling it at a low price, leaving them with a debt that takes years to repay. Therefore, maintaining a liquid market is crucial for its safety, and limiting leverage further enhances its security.

Bureaucratic interventions

In the wake of the Great Depression and World War II, government and central bank interventions have become standard tools for bureaucrats to manage the capitalist economy. Fiscal policies involve steering the economy through government expenditures. Ideally, it works as follows. When the economy is performing poorly due to sluggish demand, the government increases spending to boost demand. Conversely, when the economy is overheating due to excessive demand, the government reduces spending to curb demand. Likewise, central banks can lower interest rates to promote borrowing and boost demand, or raise interest rates to discourage lending and curb demand. These policies can have the following undesirable consequences:

- The timing of the measures may be off, so when the measure has been decided upon and is taking effect, the economy may already be on the desired path.

- Politicians may interfere and press for increased government spending or lower interest rates to boost the economy and get them re-elected.

- Central bank interventions cause market participants to take more risk because they expect the central bank to intervene.

- Due to usury, debt levels increase, so once these policies are commonplace, there are no corrections to cleanse the system from its excesses.

By failing to periodically cleanse the financial system of its excesses, either through a debt jubilee or an economic depression, the economy becomes addicted to credit expansion, and the final collapse will be even more severe. As the US dollar is the world’s reserve currency, a collapse in trust in this currency can trigger a global economic apocalypse. Usury is the primary reason for fiscal and monetary policies, because interest on money and debts generates a money shortage, driving a demand for credit. Debtors must repay more than they borrowed, but that extra money doesn’t exist. And so, governments and central banks fill the gap to prevent the usury scheme from collapsing.

Due to usury, it has become a permanent requirement. To prevent a shortage of money or a liquidity crunch from materialising, governments borrow, and central banks print money. The shortage arises when the private sector fails to borrow enough to cover the interest on existing debts. To counter the problem, the government can borrow and spend this money. Central banks can lower interest rates to make borrowing more attractive. They do so by buying up government debt, thereby decreasing the supply of government debt and increasing the supply of currency, which lowers interest rates because there are fewer debts and more currency to buy them with.

Economists assume that there is a natural interest rate at which the economy grows at its trend rate while inflation is stable. There is no direct way to measure or calculate the natural interest rate. Economists estimate it using their theories and models. The elusive natural interest rate is a crucial element in central bank decisions. The natural interest rate may differ from the actual interest rate due to credit in the financial system. Deviations from this rate trigger booms and busts. The interest rate below the natural rate can generate a boom. In that case, people borrow too much because interest rates are too low, leading to overspending and overinvesting. An interest rate above the natural rate can lead to a bust, resulting in underinvestment and underspending. By setting short-term interest rates and thereby influencing long-term rates, central banks steer credit creation.

The economy can do well by itself

With Natural Money, the economy can manage itself, making fiscal and monetary policies redundant. The holding fee removes the zero-lower bound, providing stimulus during economic slumps. The maximum interest rate curbs lending during economic booms, providing austerity. That mitigates business cycles. And so there will be fewer debt overhangs and financial crises. The market, combined with the price control of the zero upper bound, steers interest rates and the money supply, thereby reducing the role of central banks. The central bank’s currency will then become a unit of account or administrative currency. Natural Money has the following favourable consequences:

- The holding fee on currency allows for negative interest rates to provide a stimulus, while the maximum interest rate provides austerity by curbing lending.

- As interest is also a reward for taking risks, a maximum interest rate will take away the incentive to take risks and limit lending to the safest borrowers.

- In the absence of usury, debt levels don’t increase, while only the safest borrowers can borrow, resulting in fewer bad debts.

There is no need for governments to engage in deficit spending, except to provide liquidity in financial markets, as government debt, rather than administrative currency, serves as a form of liquidity. The holding fee makes it unattractive to own administrative currency. Provided their finances are sound, governments can borrow at negative interest rates and earn interest on their debts. They could aim for the debt level giving the highest interest income. If market participants are willing to lend at -1% when government debt is 100% of GDP and at -2% when government debt is at 70% of GDP, the government could harvest 1% of GDP in the former case and 1.4% of GDP in the latter case.

It will be the end of fiscal and monetary policies. The economy will manage itself. Interest payments don’t create a need to add additional debts. Governments may step in during a crisis to restore trust in the financial system and the economy, but whether such intervention will be necessary is unclear, as there will likely be fewer crises. Natural Money also doesn’t require central banks to do more than handle the daily transactions between banks, as the holding fee terminates the demand for the central bank’s currency.

Latest revision: 12 November 2025