Religion in the time of Jesus

Before he was born, a visitor from heaven told his mother that her son would be divine. Unusual signs in the heavens accompanied his birth. As an adult, he left his home to become a travelling preacher. He told everyone not to be concerned about earthly lives and material goods but to live for the spiritual and eternal. He gathered several followers who believed he was the Son of God. He did miracles, healed the sick, cast out demons, and raised the dead. He aroused opposition among the ruling authorities, and they put him on trial. After he died, he appeared to some of his followers, who later wrote books about him. This story is not about Jesus of Nazareth, but Apollonius of Tyana, as Bart Ehrman tells us in his book, How Jesus Became God.1 In those times, it was not as unusual to call someone the son of a god as it is today.

The parallels between Jesus of Nazareth and Apollonius of Tyana are striking. In ancient times, there was no chasm between the divine and the earthly realm. Critics of Christianity used these similarities to question and mock Christianity. The miracles attributed to Jesus were not exceptional either. Other men allegedly did similar deeds. Legends about people occasionally emerge. People claim that Elvis still lives and that they have seen him. Was Elvis resurrected? Who is to say that Christians didn’t invent the tales about the miracles Jesus performed? The Gospels contain contradictions, and scholars believe Christians have modified, embellished or invented these stories. Ehrman argues that the authors never intended them to be an exact account of what happened, but rather to spread the good news about Jesus. Discovering the truth later can be a daunting task. And success is not guaranteed. It has been the work of biblical scholars for centuries.

In Greek and Roman mythology, gods had sex with human beings and begot godlike children. The Greek god Zeus had a son with Alcmena, who bore a godlike son, Hercules. Miraculous and virgin births also occurred. In Roman mythology, the mother of the founders of Rome, Romulus and Remus, was said to be a virgin. Greek mythology also features a few virgin births. Leaders claimed to be the sons of the gods. Julius Caesar claimed to be a descendant of the goddess Venus. Of Alexander the Great, claims circulated that his father was the Greek supreme deity, Zeus. Kings in the ancient world often claimed to have divine parentage. That gave them legitimacy, for who dares to go against the will of the gods? Jewish kings were also referred to as sons of God (2 Samuel 7:14, Psalms 2:7). If Jesus called himself the Son of God, he could have meant that he was the king of the Jews. And that was the official reason for his crucifixion.

God came down in a human form as Mary Magdalene. Jesus claimed She was the reincarnation of Eve while he was Her son, Adam. They were the parents of humanity. The deification of Christ couldn’t have occurred in the pure monotheist Jewish tradition. However, Christianity also had non-Jewish followers who had no problems whatsoever with the all-powerful Creatrix marrying the eternal godlike human Jesus. It was a recipe for theological mayhem that Paul later succeeded in resolving by making Christian theology unfathomable. After the Romans levelled the Jewish temple and Jesus’ return had not materialised, Christianity also had to compete with the Roman emperor cult that worshipped Roman emperors as gods, making some believe it is the reason why Christians made Jesus divine. The competition was tough, and Christianity won. No one thinks of dead Roman emperors as gods anymore, but billions of people still believe that Jesus is godlike and still lives. Now, that is a miracle.

Intentional obscurity

The Gospels date from decades after Jesus’ disappearance, which has led many scholars to believe them unreliable historical sources. Church tradition holds that Mark reflects a testimony given by Simon Peter, as this gospel accurately describes words and deeds. Scholars also conclude that the Gospels describe what Jesus said and did. Much is plausible, given the time and place in which he lived. The Gospels also reveal things that Christians would not have made up, as they undermine their teachings. John the Baptist baptised Jesus. The one who baptises is spiritually superior to the one receiving the baptism.1 It implies that John the Baptist was Jesus’ teacher. The beginning of Mark also suggests so.

To make this uncomfortable fact more palatable, the Christians might have added that John said someone more powerful than he was would come, whose sandals he was not worthy to unfasten (Mark 1:7-8, Matthew 3:11, Luke 3:16, John 1:26-27). All four Gospels mention it, so John the Baptist may well have said it. Parts of the Gospels might be copies from earlier texts that are now lost. If these sources were decades older, fewer errors might have crept in, as written texts don’t change as much as oral stories during retelling.

Paul could have written about what transpired, but did not, or at least as far as we know. The obscurity seems intentional. The first three Gospels are remarkably similar. Scholars believe the sources for the Gospels of Matthew and Luke are the Gospel of Mark and another text with the sayings of Jesus. The Gospels have an unclear origin, and the authors weren’t people close to Jesus. There may have been an insider account that served as the basis for the Gospel of John.

The Gospels claim that Jesus claimed to be the Son of God and called God Father. That looks like a close relationship. To Jesus, being the Son of God meant more than merely being king of the Jews. In The Parable of the Ten Virgins, the kingdom of heaven is compared to a wedding where the bridegroom was a long time in coming (Matthew 25:1-13). All the synoptic Gospels hint at Jesus being the bridegroom. The Romans convicted Jesus of claiming to be king of the Jews. In the Jewish understanding, the king of the Jews is a son of God. But Jesus might have believed himself to be Adam, the eternal Son of God, and perhaps for that reason, also king of the Jews.

Clouding our understanding

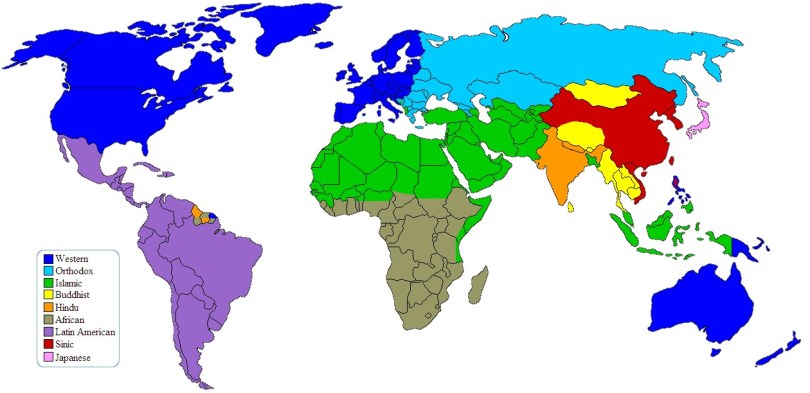

The Jewish religion and its scriptures cloud our understanding. To understand God, we must see this universe as the product of an advanced humanoid civilisation that exists to entertain one of its members, whom we call God. And so, there could be more to the mysterious apocalyptic prophet who felt a close relationship with God 2,000 years ago. After all, he started a religion with over two billion followers today. Christianity originated as a branch of Judaism, a religion characterised by its scriptures. Their scriptures outline how Jews, Christians and Muslims see the owner of the universe. That is like looking through glasses covered with dust. It distracts us from the underlying truth.

Christians say that God is love. Christianity paints a different picture of God than Judaism and Islam, which present us with a vengeful warrior God. Many religious people think the scriptures are infallible. So, how can we explain the discrepancies if the God of Judaism, Christianity and Islam is the same? Paul likely went to great lengths to align Christianity with existing Jewish doctrine. Paul and his henchmen obscured the most controversial parts of the new religion by making cryptic references to the Jewish scriptures. Had God appeared as an ordinary woman who married Jesus, and Jesus had preached somewhere else, for instance, in Egypt or China, Christianity would have been a different religion.

Biblical scholars reason from what they can establish from historical sources, while Christians believe the Jewish deity Yahweh is Jesus’ father. Both see Jesus within a Jewish context. That obscured things, as Yahweh is the imagined deity of the Jews, not the owner of the universe. It is better to view Yahweh as the cloak behind which our Creatrix hides. The most pressing problem for Paul was that God is a woman who had a romantic relationship with Jesus. To suggest so was blasphemy in the Jewish religion. And so, Jesus married the Church, just as Yahweh married the Jewish nation. It made Jesus eternal and godlike. That was not a great leap if he was Adam, God’s eternal husband.

Firstborn of all creation

Jesus thought himself to be the reincarnation of Adam. Adam was God’s son (Luke 3:38) and Jesus the firstborn of Creation (Romans 8:29, Colossians 1:15, Hebrews 1:6, 12:23). These words relate to the Jewish scriptures. At the same time, they are cryptic references to Adam being born first as the son of Eve, and Jesus being the reincarnation of Adam. The phrase born of God (John 1:13) relates to Eve giving birth to humanity. The context of the Jewish religion made it possible to hide that meaning. In traditional agricultural societies, the firstborn son inherited the land and the leadership of the family clan. The Jews were no exception. The theme appears numerous times in the Jewish Bible. The story of Jacob and Esau is well-known. King David was God’s firstborn son (Psalm 89:27).

The Jewish nation, Israel, is God’s firstborn son (Exodus 4:22). Israel is also God’s Bride (Isaiah 54:5, Hosea 2:7, Joel 1:8). This provided Paul with a theological escape, as God had married His firstborn son, Israel. God marrying Her firstborn son, Jesus, and them having a romantic relationship was impossible in Judaism. For Jews, who followed Jesus because he was the Messiah, it was impossible to conceive that their invisible deity Yahweh had taken a human form and had married Jesus, and that Jesus was not an ordinary prophet, but Adam reincarnate. And so, Jesus married the Church instead. In this way, Jesus became like God, and the Christians became Jesus’ people, just like the Jews were God’s people. And that made Jesus like God.

Jesus as God

That is not as problematic as it might seem. Many Jews believe there are two powers in heaven.1 In Genesis, God speaks in the plural, ‘Let us make humankind in our image.’ It may be a relic of the polytheist past of the Jews when they still believed the gods created the universe. When they became monotheists around 400 BC, most of the Jewish Bible, the Tanakh, had already been written. In a simulation created by an advanced humanoid civilisation to entertain one of its members, the gods in plural, creating us, also makes sense. The beings of this civilisation are the gods, and the owner of this universe is God. The monotheist Jews didn’t see it this way, so this phrase fuelled speculation about a godlike figure working alongside God.

In the Jewish Bible, God appeared from time to time. Some people saw God sitting on a throne (Exodus 24:9-10), while no one has ever seen God and lived (Exodus 33:20). Others saw the Angel of the Lord, who is also considered a manifestation of God, and survived. Abraham and Hagar are among those who have seen the Angel, and the Jewish Bible then tells us that they have seen God. Hence, the Angel of the Lord is God, but not God himself. Otherwise, they would not have survived.1

Then you have the mysterious figure Melchizedek, who might have been the Angel of the Lord, or Jesus, according to some interpretations. Melchizedek, as God’s priest, offered bread and wine to Abraham (Genesis 14:18-20), reflecting Christ’s eternal priesthood. And so, there must be two gods, an invisible, all-powerful Creator and his visible, godlike sidekick. It is an example of the assumption of the scriptures’ infallibility, combined with strict logic, leading to the absurd.

Jesus could be the Angel of the Lord and the image of the invisible God (Colossians 1:15). This interpretation is contrived, as it is not what the authors of the Jewish Bible intended. The Angel of the Lord didn’t say to Abraham, ‘I am Jesus, God’s one and only son.’ He could have done so if he were. That would have saved us a lot of theological troubles, as the Jews would have known that Jesus was the Messiah. However, for an undisclosed reason, the Angel didn’t bother to update the Jews on this interesting matter. Christians found other references to Jesus as well, such as (Daniel 7:13-14),

In my vision at night I looked, and there before me was one like a son of man, coming with the clouds of heaven. He approached the Ancient of Days and was led into his presence. He was given authority, glory and sovereign power; all nations and peoples of every language worshipped him. His dominion is an everlasting dominion that will not pass away, and his kingdom will never be destroyed.

That must be Jesus, Christians claim. Jews disagree.

The road to Trinity

A problem early Christians had to solve was that Jesus was the Son of God and also God, while there was only one God. That didn’t make sense. It kept Christian thinkers busy for centuries until they reached an agreement on the Trinity. Christianity is a scriptural religion, so there must be a justification in the scriptures. The Gospel of John starts with the following sentence, ‘In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.’ The Word was with God, and the Word was God. The Word was Jesus, as the Word became flesh and made his dwelling among us. In other words, Jesus is God, and he existed before Creation. But he is not God the Father, but with God the Father. God consists of the Father and the Son, while God is one.

In the ancient world, some gods came in threes or triads. The Indian religion has the group of Brahmā, Siva, and Viṣṇu, and the Egyptians had Osiris, Isis, and Horus. It was called Trinity. That required adding another component to the mixture of the Father and the Son to arrive at three ingredients and find a theological justification. The idea of the Trinity circulated among Christians as early as 150 AD and became an official teaching in the fourth century AD. So, what could be the scriptural justification for the Trinity? Christians found it in Isaiah (Isaiah 9:6),

For to us, a child is born, to us a son is given, and the government will be on his shoulders. And he will be called Wonderful Counsellor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace.

Some see a reference to the Trinity there. Counsellor is a title for the Holy Spirit (John 14:26), the Father is God, and the Prince of Peace is Jesus. That is far-fetched. But there is a better one. Some see the Trinity when the Jewish Bible refers to God’s Word (Psalm 33:6), His Spirit (Isaiah 61:1), and Wisdom (Proverbs 9:1). But what could be the theological justification?

Greek philosophy influenced Jewish scholars, such as Paul. Plato claimed that ideas are the basis of knowledge. Thus, ideas, not physical objects, are the building blocks of reality. In Platonic thinking, the world of ideas is superior. Platonists think that a spirit can use words to produce matter. God is a pure spirit, the highest being. In Judaism, God created all things using words. Hence, words existed before Creation. Otherwise, you can’t make the world using words.

The Jewish philosopher Philo lived at the same time as Jesus. He claimed the Word is the highest of all beings, the image of God, according to which and by which the universe receives its order. Philo called the Word the second God. But if there is one God, the Word must be part of God. The author of the Gospel of John took that idea, and it starts with, ‘In the beginning was the Word.’ Here, the Word was Jesus, so Jesus existed before Creation. And that became a teaching of Christianity.

In Proverbs, Wisdom says that she was the first thing God created. And then God created everything else with the help of Wisdom alongside Him (Proverbs 8:22-25). She is a reflection of the eternal light, a spotless mirror of the working of God, and an image of His goodness (Wisdom 7:25-26). Wisdom is feminine because it is a feminine term in the Greek language. Greek was the language of the time, and educated Jews spoke Greek, and Jewish scriptures were translated into Greek. Here, Wisdom plays a similar role as the Word. She was present when God made the world and is beside God on his throne (Wisdom 9:9-10). Hence, Wisdom was also extant before Creation. And so, you have the Word, the Wisdom, and God existing before Creation. If the Word had become Jesus, Wisdom could have become the Holy Spirit. And so we arrive at the Trinity. This explanation also clarifies why the Holy Spirit is feminine.

Logical issues leading to an arcane theology

Christianity originated as a Jewish sect, so early Christians based their religion on the Jewish scriptures. It generated problems, as the facts contradicted the scriptures, most notably that God is a woman who can take a human form. Jesus as Adam, God’s eternal husband, already made him godlike. The efforts to resolve these logical difficulties shaped the concept of Jesus as God. Had Jesus preached in Egypt instead and claimed his wife was the goddess Isis, the all-powerful Creatrix of the universe, and that he was the reincarnation of her son Horus, there may still be records of his teachings.

Egypt was a polytheistic nation with more flexible beliefs. It could have adopted another colourful cult alongside the existing ones. The Jews, however, were monotheists with well-established scriptures, which also made Christianity uncompromisingly monotheistic. Converts had to renounce all false gods, allowing Christianity to wipe out the other religions and religiously cleanse the Roman Empire. And it all would have been inconceivable without the intervention of one of the greatest religious innovators of all time, Paul. He invented Christianity. That almost looks like a plan.

Latest revision: 31 January 2026

Featured image: Christ Pantocrator in Hagia Sophia. Svklimkin (2019). Wikimedia Commons.

1. How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher. Bart D. Ehrman (2014). HarperCollins Publishers.