End of growth

The last 200 years have been an era of exceptional economic growth, unlike anything the world has ever seen. Like any exponential phenomenon in a limited room, that growth will end. The best comparison is cancer. If it goes untreated, the host dies. The end of growth, whether it is by death of the host or treatment, has implications for capital, which is addicted to positive returns made possible by squandering planetary reserves. For most of history, there was a shortage of capital. But for the first time, there is a massive excess invested in the bullshit economy, transforming energy and resources into waste and pollution to make money for investors by producing and marketing non-essential products and services in a competition that is about to make humans redundant.

For most of history, economic growth has been negligible. However, it averaged 1.5% over the last two centuries and will soon return to zero, or possibly even lower, perhaps much lower. That has implications for returns on investments, the financial system and interest rates. Investors have become hooked on positive returns, so there must be growth. Otherwise, they lose confidence. It is grow or die, but growth will kill us. And so, we face the prospect of an economic collapse and a collapse of civilisation. We are near a technological-ecological apocalypse. There is a dark force operating behind the scenes that makes us commit suicide. It is usury, or the charging of interest on debts. It makes capital addicted to growth.

The survivors may debate the precise cause of the collapse. I have already received a newsletter email from a pundit claiming that a lack of very cheap oil is leading to debt problems. Future generations may blame the planet for being finite, rather than seeing that human beings were so foolish as to build their civilisation on usury, so that it can only survive through economic growth. Before modern times, humans managed to live without economic growth, as there was hardly any capital and no interest-bearing debt. Past civilisations facing usury-induced economic collapses either disappeared, banned interest, or instituted debt cancellations.

The past 200 years have indeed been exceptional, and that miracle was primarily due to low interest rates. Efficient financial markets promoted growth by depressing interest rates, allowing economic growth to finance the interest. That has blinded us from the financial apocalypse that is upon us. Low interest rates have already brought us unprecedented wealth, albeit at the expense of the planet and future generations. When economic growth returns to sustainable levels, the interest on outstanding debt can collapse the world economy and bring down human civilisation. Luckily, a usury-free financial system for a future without growth already exists: Natural Money.

The nature of usury

Suppose Jesus’ mother had opened a retirement account for Jesus just after his birth in 1 AD at the Bank of the Money Changers next to the Temple in Jerusalem. Suppose she had put a small gold coin weighing three grammes in Jesus’ retirement account at 4% interest. Jesus never retired, but he promised to return. Suppose now that the bank held the money for this eventuality. How much gold would there be in the account in the year 2020? It would be an amount of gold weighing twelve million times the mass of the Earth. There isn’t enough gold to pay out Jesus if he returns.

And so the usurers hope he doesn’t come back, also for other reasons, of course. And for every lending, there is borrowing. The bank is merely an intermediary. There must be people in debt for an amount of gold weighing twelve million times the mass of the Earth. That would never happen. The scheme would have collapsed long before that, and the debtors would have become the serfs of the money lenders. That is why religions like Christianity and Islam forbade charging interest on money or debts.

The usurers have found a way around the issue. Our money isn’t gold anymore. Banks create money from thin air, so the nature of usury has changed. When you go to a bank and take out a loan, such as a car loan, you get a deposit and a debt, which the bank creates on the spot through two bookkeeping entries. You keep the debt, but the deposit becomes someone else’s money once you purchase the car. When you repay the loan, the deposit and the debt vanish into thin air. You must repay the loan with interest. If the interest rate is 5% and you have borrowed €100 for a year, you must return €105.

Nearly all the money we use is created from loans that borrowers must repay with interest. If our borrowing creates money, and we repay our debts with interest, then we may do so by borrowing the interest. That is also what happens in reality, and that is why debt levels continue to rise. So, where does the extra €5 come from? Here are the options:

- Borrowers borrow more.

- Depositors spend some of their balance.

- Borrowers fail to repay their loans.

- The government borrows more.

- The central bank prints the money.

Problems arise when borrowers don’t borrow more, and depositors don’t spend their money. In that case, borrowers as a group are short of funds, and some of them are unable to repay their loans. If too many borrowers can’t pay at once, a financial crisis occurs. To prevent that from happening, the government borrows more, and the central bank prints money. They bring that money into the economy, allowing debtors to pay off their debts with interest. Interest compounds to infinity, and there is no limit to human imagination, so frivolous accounting schemes can go a long way before they collapse.

Necessity of interest

We take interest for granted, and economists believe that the economy needs it. Without lending and borrowing, a modern capitalist economy would have been impossible; without interest, loans would also be impossible. Money is to the economy what blood is to the body. If lending and borrowing halt, money stops flowing, and the economy comes to a standstill. That is like a cardiac arrest, which, if untreated, is fatal. And that is also why the financial press reads the lips of central bankers as if our lives depended on it. They manage the flow. Lenders have reasons to demand interest. These are:

- When you lend out money, you can’t use it yourself. That is inconvenient. And so, you expect compensation for the use of your money.

- The borrower may not repay the loan, so you desire compensation for that risk.

- You can invest your money and earn a return. To lenders, the interest rate must be attractive relative to other investments.

That has been the case for a long time, and economists have gradually become quite good at explaining the past. Since then, we have seen financial innovations and are now facing the end of growth. Changes in the economy and the economic system may lead to the end of interest on money and debts. These are:

- You can use the money in a bank account at any time. You can use the money you have lent as if it were cash. And a debit card is more convenient than cash.

- Banks spread their risks, central banks help out banks when needed, and governments guarantee bank deposits, so bank deposits are as safe as cash.

- There is a global savings glut. There are ample savings and limited investment options, which can make lending at negative interest rates attractive.

Negative interest rates are possible. In the late 2010s and early 2020s, the proof came when most of Europe entered negative interest-rate territory. The ECB was unable to set interest rates below -0.5%. Had it set interest rates even lower, account holders would have emptied their bank accounts and stuffed their mattresses with banknotes to avoid paying interest on their deposits, disrupting the circular flows.

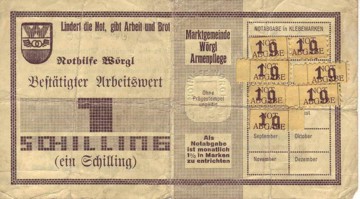

As interest rates couldn’t go lower, the ECB took extraordinary measures, flooding the banking system with new money to boost the economy. Had there been a holding fee on cash, interest rates could have gone lower, and there would have been no need to print money. It has happened before. The Austrian town of Wörgl charged a holding fee on banknotes during the Great Depression, which led to an economic miracle by making existing banknotes circulate better rather than printing new money. Ancient Egypt had a similar payment system for over a thousand years during the time of the Pharaohs.

Miracle of Wörgl

In the midst of the Great Depression, the Austrian town of Wörgl was in dire straits and prepared to try anything. Of its population of 4,500, 1,500 people were jobless, and 200 families were penniless. Mayor Michael Unterguggenberger had a list of projects he wanted to accomplish, but there wasn’t enough money to fund them all. These projects included paving roads, installing street lights, extending water distribution throughout the town, and planting trees along the streets.1

Rather than spending the remaining 32,000 Austrian Schilling in the town’s coffers to start these projects, he deposited them in a local savings bank as a guarantee to back the issue of a currency known as stamp scrip. A crucial feature of this money was the holding fee. The Wörgl money required a monthly stamp on the circulating notes to keep them valid, amounting to 1% of the note’s value. The Argentine businessman Silvio Gesell first proposed this idea in his book The Natural Economic Order.2

Nobody wanted to pay for the monthly stamps, so everyone spent the notes they received. The 32,000 schilling deposit allowed anyone to exchange scrip for 98 per cent of its value in schillings. Few did this because the scrip was worth one Austrian schilling after buying a new stamp. But the townspeople didn’t keep more scrip than they needed. Only 5,000 schillings circulated. The stamp fees paid for a soup kitchen that fed 220 families.1

The municipality carried out the works, including the construction of houses, a reservoir, a ski jump, and a bridge. The key to this success was the circulation of scrip money within the local economy. It circulated fourteen times as often as the schilling. It increased trade and employment. Unemployment in Wörgl decreased while it rose in the rest of Austria. Six neighbouring villages successfully copied the idea. The French Prime Minister, Édouard Daladier, visited the town to witness the ‘miracle of Wörgl’ himself.1

In January 1933, the neighbouring city of Kitzbühel copied the idea. In June 1933, Mayor Unterguggenberger addressed a meeting with representatives from 170 Austrian towns and villages. Two hundred Austrian townships were interested in introducing scrip money. At this point, the central bank decided to ban scrip money.1 The depression returned, and in 1938, the Austrians turned to Hitler, as they voted to join Germany.

Since then, several local scrip monies have circulated, but none has been as successful as the one in Wörgl. In Wörgl, the payment of taxes in arrears generated additional revenue for the town council, which it then spent on public projects. Once the townspeople had paid their taxes, they would have run out of spending options and might have exchanged their scrip for schillings to avoid paying for the stamps. That never happened because the central bank halted the project.

The economy of Wörgl did well because the holding fee kept the existing money circulating. A negative interest rate encourages people to spend their money, eliminating the need to borrow and keeping the money circulating in the economy. It demonstrated that the economy required a negative interest rate. A holding fee makes negative interest rates possible, as lenders do not have to pay it after lending the money. The one who holds the money pays the charge. That can make lending money at an interest rate of -2% to a reliable borrower more attractive than paying 12% for the stamps.

Joseph in Egypt

In the time of the Pharaohs, the Egyptian state operated granaries for over 1,500 years. Wheat and barley were the primary food sources in Egypt. Whenever farmers brought their harvest to one of the granaries, state officials issued them receipts stating the amount of grain they had brought in. Egyptians held accounts at the granaries. They transferred grain to others as payment or withdrew grain after paying the storage cost.

The Egyptians thus used grain stored in their granaries for making payments. Everyone needed to eat, so grain stored in the granaries had value.1 Due to storage costs, the money gradually lost its value. With this kind of money, you might have interest-free loans. If you save grain money, you pay for storage. And so, lending the money interest-free to a trustworthy borrower can be attractive. There is no evidence that this happened.

The origin of these granaries remains unclear. Probably, the state collected a portion of the harvests as taxes and stored them in its facilities. The government storage proved convenient for farmers, as it relieved them of the work of storing and selling their produce. And it made sense to have a public grain reserve in case of harvest failures.

The Bible features a tale that supposedly explains the origin of these granaries. As the story goes, a Pharaoh once had a few dreams that his advisers couldn’t explain. He dreamed about seven lean cows eating seven fat cows and seven thin, blasted ears of grain devouring seven full ears of grain. A Jewish fellow named Joseph explained those dreams to the Pharaoh. He told the Pharaoh that seven years of good harvests would follow, followed by seven years of crop failures. Joseph advised the Egyptians to store food for meagre times. They followed his advice and built storehouses for grain. In this way, Egypt managed to survive seven years of scarcity.

The money gradually lost value to cover the storage cost of the grain. It works like buying stamps to keep the money valid, like in Wörgl. Both are holding fees. The grain money circulated for over 1,500 years until the Romans conquered Egypt around 40 BC. It did not end in a debt crisis, which suggests that a holding fee on money or negative interest rates can create a stable financial system that lasts forever.

Storing food makes sense today, even when it costs money. Harvests may become more unpredictable due to global warming and intensive farming. We only have enough food in storage to feed humanity for a few months as it is unprofitable to store more. Food storage ties up capital, so there is also interest cost. But you can’t eat money, so storing food to deal with harvest failures is as sensible now as it was in the time of the Pharaohs. It reveals the stupidity of our current thinking. Our survival needs to be financially viable. Just imagine how that will play out once artificial intelligence and robots can replace us.

Natural Money

The miracle of Wörgl suggests that a currency with a holding fee could have ended the Great Depression. A myth circulating in the interest-free currency movement is that had the Austrian central bank not banned the experiment, the Great Depression would have ended, Hitler wouldn’t have come to power, and World War II wouldn’t have happened. That is a tad imaginative, to say the least, but a holding fee could have allowed for negative interest rates, and they could have prevented the Great Depression from starting in the first place. That is a lot of maybes.

And such money can last. The grain money in ancient Egypt provided a stable financial system for over 1,000 years. The grain backing provided financial discipline. The holding fee prevented money hoarding that could have impeded the flow of money. The money, however, didn’t promote interest-free lending, so the Egyptian state regulated lending at interest to prevent debt slavery. Egyptian wisdom literature condemned greed and exploitative lending, encouraging empathy for vulnerable individuals.

A holding fee of 10-12% per year punishes cash users. If the interest rate on bank accounts is -2%, an interest rate of -3% on cash is sufficient to prevent people from withdrawing their money from the bank. That becomes possible once cash is a separate currency backed by the government, on which the interest rate on short-term government debt applies. Banknotes and coins thus become separate from the administrative currency. So, if the interest rate on the cash currency is -3%, one cash euro will be worth 0.97 administrative euros after one year. And now, we have a definition of Natural Money:

- Cash is a separate currency backed by short-term government debt and has the negative interest rate of short-term government debt.

- Natural Money administrative currencies carry a holding fee of 10-12% per year, allowing for negative interest rates.

- Loans, including bank loans, have negative interest rates. Zero is the maximum interest rate on debts.

Consequences

Natural Money doesn’t fundamentally alter the nature of bank lending. Banks borrow from depositors at a lower rate to lend it at a higher rate. With Natural Money, banks may offer deposit interest rates of -2% to lend it at 0% instead of borrowing it at 2% to lend it at 4%. A maximum interest rate of zero, however, has a profound impact on lending volume, as it severely constrains it, most notably speculative lending and usurious consumer credit, and it favours equity financing over borrowing in business. The strict lending requirements affect business loans, leading to deleveraging.

Businesses still need to attract capital. To address the issue, Natural Money features a distinction between regular banks and investment banks. Regular banks can guarantee promised returns and have government backing because the payment system is a public service. Investment banks invest in businesses and take risks. They are comparable to Islamic banks. Investment banks don’t guarantee returns. Depositors take on risk to get better returns, but they might incur losses or temporarily have no access to their deposits.

While the maximum interest rate restricts lending, the holding fee provides a stimulus, thereby stabilising the financial system. When the economy slows down, interest rates decrease, and more money becomes available for lending as risk appetite increases, making lending at zero interest more attractive. Conversely, if the economy booms, interest rates increase, and the maximum interest rate curtails lending. Consequently, central banks don’t need to set interest rates and manage the money supply, and governments don’t need to manage aggregate demand with their spending.

Reasons to do research

Stamp scrip and other kinds of emergency money have helped communities in times of economic crisis. The economic miracle of Wörgl during the Great Depression of the 1930s, however, was exceptional. The payment of local taxes inflated the impact of the money. Many townspeople had been late on their taxes, but once the economy recovered, they had the money to pay them. Some even paid their taxes in advance to avoid paying the holding fee. It generated additional revenues for the town, which it could spend on the projects. It provided a boost that would have petered out once the villagers had paid their taxes.3 It was not a miracle. It was too good to be true. Still, there is more to it.

Once interest rates reach zero, the markets for money and capital cease to function as interest rates can’t go lower. Money is to an economy what blood is to a body, so it must flow. When the money stops flowing, the effect is like a cardiac arrest, and the economy is in dead waters. To keep the money circulating, those with a surplus must lend it to those with a deficit, and the interest rate should be where the supply and demand for money are equal. When that interest rate reaches zero, lenders stop lending because the return is not worth the risk, so they wait for interest rates to rise. Money then ends up on the sidelines, leading to cardiac arrest, which can be the start of an economic depression.

It happened during the Great Depression. If interest rates had been lower, the markets for money and capital could have remained in operation. We have seen negative interest rates in Europe for nearly a decade. They could have gone lower had there been a holding fee on cash, or even better, a negative interest rate that is just low enough to prevent people from hoarding it. Once interest rates can go lower, a usury-free global financial system may be possible. That gives rise to several questions. Is it possible? Under which circumstances? What are the benefits and the drawbacks? What are the implications for individuals, businesses and governments? And how does it affect the financial system?

There is no alternative

Several other monetary reform proposals do not view the financial system as a system, which it is, and that isn’t hard to guess because the term ‘financial system’ already implies this. You can’t attach the wings of a Boeing to an Airbus and expect the thing to fly. The financial system is a complex system with numerous relationships, many of which existing reform proposals overlook. For instance, if you end the central bank, the economy will crash immediately, even if it is flying smoothly. And that isn’t even hard to find out.

The payment system is a key public interest, so governments and central banks stand behind it. Most banks are private corporations driven by profit. They take risks that might bring down the economy. And so, governments and central banks make regulations and oversee the banks. And banks create money, from which they profit, and we all pay for it via inflation. That is not good, but replacing the system with something worse is worse, like the word ‘worse’ implies.

There is no lack of ill-conceived proposals. And most fail to address the primary underlying cause of the dysfunction of the financial system, which is charging interest on money and debts, commonly known as usury. An inflation-free, stable financial system is possible. It may not even need central banks. But a sound reform proposal sees the financial system as a complex system with intricate relationships that interact with one another.

And so, Natural Money comes with a systems approach that aims to uncover the relevant relationships in the financial system and the consequences of changing them. It means that Natural Money is a comprehensive design. The gravest error you can make is to pick only the elements you like. That design will never fly. Nor would an Airbus take off with Boeing wings. So, you either buy Airbus or Boeing. In the case of Natural Money, that is not an option. There is no alternative.

Latest revision: 1 November 2025

Featured image: Wörgl bank notes with stamps

1. The Future Of Money. Bernard Lietaer (2002). Cornerstone / Cornerstone Ras.

2. The Natural Economic Order. Silvio Gesell (1918).

3. A Free Money Miracle? Jonathan Goodwin (2013). Mises.org.