Lessons of history

Societies and civilisations have collapsed in the past, so history can teach us something about what awaits us. Theories about collapse are speculative. Different explanations are possible. Whereas the debates between the experts are still raging, time is running out. Collapse could be coming. It will be brutal if we don’t prepare. We should heed the lessons from history. It may turn out we were wrong. But that is for the critics in their armchairs to observe someday when their lives aren’t at risk. And they will have the benefits of hindsight. We can only make the best decisions with our present knowledge.

The fall of the Western Roman Empire is the most well-known example of collapse. In the second century AD, diseases reduced the Roman population, eroding the empire’s tax base. The empire had a long border to defend, so emperors became increasingly desperate for revenues to finance the military. Over time, taxes and measures to ward off invasions became intolerable for Roman citizens, and the Western Roman Empire broke down. Most Romans were better off with a simpler life under the rule of Barbarians.1

The population of Rome declined from 1,000,000 around 100 AD, of which many lived on government welfare, to a scanty 30,000 around 1000 AD, a drop of 97%. Most of that decline occurred in the fifth century when the empire collapsed. More than half the people live in cities today, so a possible collapse is something we should dread. Many of us depend on markets and public services. We don’t know the future, but economics drives migration. If our civilisation doesn’t collapse and living in cities is more resource-efficient, cities may not depopulate, provided people in cities can earn an income.

The Western Roman Empire was underpopulated, and the state had become a burden. Its collapse thus was a relief to many. Other collapses were worse. The Mayan civilisation broke down because the Mayans ran into the limits of their environment. The immediate cause of their collapse was drought due to a lasting drop in rainfall. State control led to increased efficiency in food production and distribution. It allowed the Mayans to feed more people who would have starved otherwise. However, the measures to increase food production had stretched their environment to the breaking point, so improving agricultural output became increasingly difficult.1

The Mayan states then reverted to warfare to plunder each other’s crops, making it even harder to maintain agricultural output. The Mayans weakened from malnourishment and warfare, and the Mayan states collapsed together. In the short term, the peasants were better off as they didn’t pay taxes to support a state. In the long run, with irrigation works and granaries abandoned and defences neglected, agricultural output collapsed, and population numbers dropped by 90%.1

That is why we should dread collapse. There will be a lack of order, and people will organise themselves in gangs. Your and your group’s survival depends on assessing other people’s intentions and killing those who might kill you. And you don’t know, so you must guess what others are up to. And it is better to be safe than sorry, so you might decide to kill people as a precaution. That may be a good script for a thriller. However, most of us prefer to live less adventurously. Had the Mayans not waged wars but cooperated peacefully to use resources more efficiently and reduce population, their civilisation might have declined more gracefully and could have survived. That was unthinkable because of the intense competition between the states and the absence of contraceptives.

Causes of collapse

History shows a repeating pattern of overshoot and collapse. A population would grow until it reached the carrying capacity of the environment. As a result, there would be fewer food surpluses to save for harvest failures. Eventually, civilisations would succumb to disease, an invasion by neighbouring tribes, weather fluctuations, or civil war. The crucial difference with the present situation is that technology stayed the same in the past. In recent centuries, technological innovations, most notably our improved ability to acquire energy from fossil fuels, have outpaced the forces contributing to collapse. The danger is that the overshoot and the coming collapse can be worse than previous ones. The advantage of new technology is that it doesn’t need to be terrible and that we can lead agreeable lives.

Jared Diamond sees five factors contributing to past collapses: climate change, which also occurred in the past, hostile neighbours, the loss of trading partners, environmental problems, and society’s response to these challenges. The underlying cause is often overpopulation.2 Increased resource extraction efficiency allowed more people to survive, worsening the situation. That was true for the Mayans but not for the Romans. The Romans had hostile neighbours but not overpopulation. Higher population numbers could have helped the Roman Empire survive.

Joseph Tainter argues that in both cases, the costs of the state exceeded the benefits. The Western Roman Empire was underpopulated, so the Romans couldn’t afford the taxes required to defend their long border. The Mayan states organised agricultural production and were initially successful. However, at some point, additional state interference didn’t generate more crops or better management of surpluses and deficits. Overpopulation or overstretching the environment puts a premium on organising, but it postpones the inevitable. And it makes the collapse worse. Had the Mayans not organised themselves in states, they would have had less food, fewer people, and no collapse.

Our predicament looks more like that of the Mayans than the Romans. Competition between states and corporations for resources may intensify, and the collapse could be brutal. Simplification and having fewer children is a way out, and we can be better off if we cooperate globally to limit consumption and reduce our populations. That doesn’t happen because it is a collective action problem only a world government can solve. Governments compete and try to boost population numbers. Ending the competition between states is paramount because power, in the form of a prosperous economy, population and military, requires resources and energy. If one state pursues power in this way, others follow.

In times of decline, even the best leaders look bad as they can only make things less lamentable than they otherwise would have been. As we notice the deterioration but don’t experience the alternative, anger and frustration can take over, and people will look for scapegoats, resulting in political instability, a breakdown of order, civil war and mob rule. Managing and turning the decline into a more graceful simplification is the best option, but that requires commitment and discipline from everyone.

Organising to solve problems

Tainter sees societal collapse as an economic calculation. Societies and civilisations collapse when the cost of their institutions exceeds the benefits. If the soil depletes due to overuse, measures to improve crop yields or manage surpluses and deficits become increasingly expensive and have lower returns. The Mayans didn’t make these calculations by keeping ledgers of incomes and expenses. At some point, their measures became ineffective, and people started starving. There is an upside to an economic view. It can help us decline gracefully and make the most of what we have.

We organise ourselves in states and corporations to solve problems. We have police to solve a security problem. We have a car factory to deal with a transportation problem. Complex organisations, like states or corporations, have costs and benefits. When you solve a problem, you may get a bigger one in return, or one is more costly to handle. When societies are simple, expenses are low, while the benefits of solutions can be substantial. A doctor’s post in the jungle might lengthen the life of local tribespeople by as much as twenty years. As the level of organisation increases, the price of additional complexity increases while the benefits decrease.

As we cure easy-to-treat diseases, people grow older and get harder-to-treat diseases. If our medical knowledge increases, we can cure some of these diseases with expensive treatments, and people will die of even harder-to-treat diseases. Medical costs explode with only marginal gains in life expectancy. Replacing the doctor’s post in the jungle with a hospital might cost five times as much and add only three years to the lives of the tribespeople. Perhaps five tribes together could afford the hospital. In complex societies, many tasks require occupational specialisation, information processing and management. There are benefits to complex organisations, but they usually come with scale. Physicians who specialise can do better jobs when enough people share the costs.

Since the Industrial Revolution, markets and energy usage expanded. Abundant fossil fuels and increases in scale have reduced the cost of organisation. And so, the benefits outweigh the expenses at a much higher level than before, allowing us to specialise further than before. In the past, over 90% of the people worked in agriculture, tilling the land. Now machines do that work, freeing up labour for other purposes. The same happened in the production of goods and services. Technological development further increased these benefits. Computers use far less energy than forty years ago for the same amount of computing power and memory. That made more uses feasible, so we use far more energy for information technology than forty years ago.

It is the curse of efficiency improvements. When technology becomes more efficient and cheaper, we use so much more of it for frivolous purposes that, as a result, we consume far more resources and energy in the end. Efficiency improvements thus don’t solve our problems and even worsen them. Once resources and energy supplies dwindle, much of what we do now will lose its purpose, just like what happened to the Mayans. Still, technological advances allow us to do much more with the same resources and energy, so if we use new technologies for essential purposes, our future can be agreeable.

Diminishing returns: an example

Life expectancy in the UK rose from forty to eighty years between 1860 and 2020. However, the costs of new complex treatments increase while their effect on life expectancy decreases. These treatments can become a burden to the population at large. Comparing the United States with Cuba illustrates the benefits of simplification. Cuba is poor compared to the United States. Many essentials are hard to come by, and the country can barely feed its people. Cuba only has rudimentary healthcare, but it is available to everyone, while the United States spends more on healthcare than any other nation. Yet, life expectancies in Cuba and the United States are on par.

Cuban healthcare gives value for money because it is simple and equally distributed. US Healthcare underperforms because it is burdened with litigation, while pharmaceutical corporations sell unnecessary or even harmful treatments and medical professionals enjoy privileges they don’t have in other countries. And healthcare is not equally available to everyone. Lifestyle affects life expectancy as well. Obesity, homicides, opioid overdoses, gang violence, suicides, road accidents, and infant deaths come into the picture.

Americans use drugs, eat fast food and drink sodas unavailable in Cuba. Cubans are dirt poor, so it isn’t profitable for drug cartels to sell them drugs. The death toll from drugs, fast food and sodas in the United States exceeds that of famines in Cuba. Americans experience more stress as workers than Cubans because they need to be competitive in a market economy that is constantly economising and improving efficiency. Many Americans die of heart disease and drug abuse.

If you grow your food and your neighbours help you build your home, nothing gets added to GDP. Eating fast food, paying high rents, drinking sodas and being treated for obesity and other diet-related illnesses are good for profits and economic growth, as are working hard and taking drugs or seeing a psychiatrist for stress symptoms. Sodas, treatments for obesity, medication and therapeutic sessions all add to GDP. Economists call it wealth creation. It may help to explain why America is wealthy. In the United States, a small group of politically connected big corporations and specialists, such as lawyers, pharmaceutical corporations, and medical specialists, make lots of money.

In complex societies, highly trained professionals earn much more than ordinary people. In some cases, we are better off without them. Imagine how much cheaper things would be if we eliminated lawyers and litigation. And think of what it will do to GDP. Indeed, Americans might be better off poorer. The Old Order Amish are happier than the average American worker. The causes of Amish life satisfaction are not a mystery. Being part of a supportive family, being a member of a well-integrated community, having a religion, and regular physical exercise all contribute to a happy life.

Managing excess

Excessive production and consumption create problems we must subsequently manage. That requires specialisms, laws, controls, and the like, and it becomes increasingly costly. And people get the impression that governments are to blame when they impose limits. Complexity and specialisation suffer from diminishing marginal returns. The costs increase while the benefits decline. Consider the issues of food production and pollution control. According to Tainter, rising world food production by 34% between 1951 and 1966 required increasing tractor expenditures by 63%, fertilisers by 146%, and pesticides by 300%. We now deal with soil degradation, which endangers our future food supply.1

Pollution control shows a similar pattern. Removing all organic waste from a sugar processing plant costs 100 times more than removing 30%. Reducing sulphur dioxide in the air of a US city by 9.6 times or particulates by 3.1 times raises the cost by 520 times. These numbers may be outdated, but the nature of the problem remains the same. Allocating more resources to R&D can provide temporary respite from diminishing returns. But R&D also has diminishing returns.1 We might increase production or contain pollution, but it can become prohibitively expensive, so it might be cheaper to produce less.

Like the Mayans, we have stretched our environment to its limits. New technology and control measures postpone the inevitable. The alternative is to consume less and have fewer children. We can do without many things, or we can produce things differently. Stable supplies of large quantities of fossil fuels sustain our current complex civilisation. Unstable supplies of renewable energy can drive a simplification. If we compensate for carbon emissions, fossil fuels become expensive, and it can be economical to reduce energy consumption and rely on renewable sources. As a result, pressures can mount to decentralise and live more simply. If we do not create problems, we do not need to fix them. For instance, what is the point of pollution legislation if there is no pollution?

When we simplify our lives, we depend more on our family and community and less on markets and states. We use local products where possible. And we have little need for people who manage the complexity. Nowadays, more than half the people live in cities, so we can’t switch overnight. Even if we simplify our lives, we can have more agreeable lives than most people for most of history. If we manage the collapse, we can be better off than we would have been otherwise. And we can adapt. The 80/20 rule states that 20% of the causes have 80% of the effects. So, 20% of our consumption might cause 80% of our well-being. Thus, our well-being might decline by 20% when we reduce resource and energy consumption by 80%. Those who lead excessive lifestyles should make the sacrifice.

Latest revision: 21 August 2024

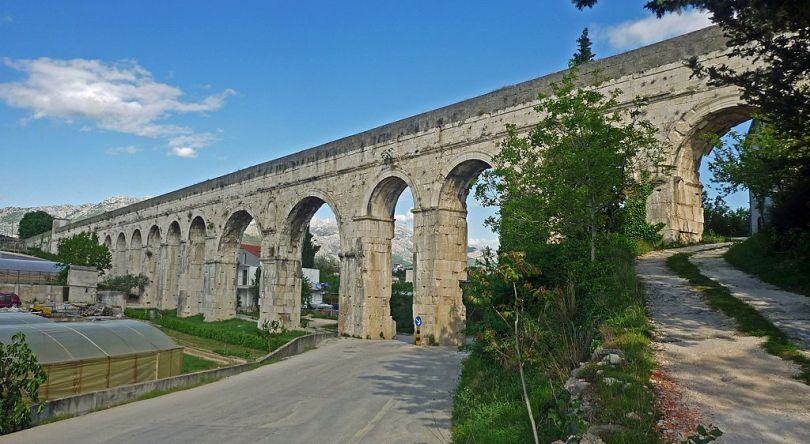

Featured image: Diocletian’s Aqueduct in Split, Croatia, built around 300 AD. User: SchiDD. Wikimedia Commons.

1. The Collapse of Complex Societies. Joseph Tainter (1988). Cambridge University Press.

2. Collapse: How societies choose to fail or survive. Jared Diamond (2005). Viking Press.