Forces of nature

How did we get where we are today? Nature’s driving forces are competition and cooperation. This perspective provides a great deal of insight into what happened. Plants and animals cooperate and compete for resources. Cooperation and competition are everywhere. Cooperation increases the available resources. Plants generate the oxygen animals need, while animals produce the carbon dioxide plants need. Still, the available resources are limited. There is only room for one tree on that spot. And so, there is a competition called the struggle for life, where the fittest survive.

Plants and animals are opportunistic, taking advantage of opportunities whenever possible, with the help of both competition and cooperation. Plants and animals have a blueprint, their genes. These genes have the urge to make copies of themselves. It is why we exist and the basis of our will to live and our sexual desires. And so, the biological purpose of plants and animals, including humans, is to spread their genes. That is indeed a most peculiar purpose. The copying of genes is prone to errors. And so changes occur, resulting in variation within species. It is why people vary in appearance and character.

Some changes make individual plants and animals better adapted to their environment, thereby increasing their chances of survival and reproduction, resulting in a rising number of individuals with these features. Environments allow for several species to coexist, most notably when they don’t compete for the same resources. It is why ants and monkeys can live in the same area. The balance in nature is always precarious, as changes in circumstances can favour different species. And so, introducing foreign species in places where they have no natural predators can lead to pests.

Like other social animals, humans operate in groups. Social animals benefit from group cooperation, which enhances their chances of survival. Within the group, competition can arise, resulting in rankings and struggles among members. Cooperating in groups also helps us to compete with other groups, usually in warfare. And groups can form coalitions to compete with coalitions of different groups. Stories enable humans to work together in groups of any size, which then further increases the competition between these groups.

Meet our closest relatives

Chimpanzees are our closest kin. Studying these apes provides us with insights into our nature. Chimpanzees live in small troops of a few dozen individuals. They form friendships, work with reliable group members, and avoid those who are unreliable. Chimpanzees have rules, may cheat on them, and can feel guilty when they do. Within the group, the members have ranks. When there is food available, the highest-status animals eat first. Ranks and rules regulate competition within the troop, reducing conflicts and enabling its members to collaborate more effectively.

Like human leaders, chimpanzee alpha males acquire their status by building coalitions and gaining support. Others show their submission to the alpha male. Like a government, the alpha male strives to maintain social harmony within his group. He takes sought-after pieces of food like a government collects taxes. Within a chimpanzee band, there are subgroups and coalitions. There are close friendships and more distant relationships. They unite as a single fighting force in the event of an external threat.

Coalition members in a chimpanzee band build and maintain close ties through intimate daily contact such as hugging and kissing, and doing each other favours. For the band to function effectively, its members must be aware of what others will do in critical situations. For that, they need to know each other through personal experiences. Unlike humans, chimpanzees have no language to share social information. That limits the size of the group in which chimpanzees can live and work together to about thirty individuals.

Chimpanzees also commit violence in groups. Like humans, they are among the species that commit genocide on their congeners. Humans and chimpanzees are not alone in this. Chickens are known to fight racial wars when they face a lack of food. Groups of chickens may start to kill those with different colours from themselves. And so, racism could be a natural behaviour caused by competition between genes.

The human advantage

Humans have become the dominant species on Earth. We can collaborate flexibly in large numbers. We have mastered fire, which enhances our power and allows us to eat foods we couldn’t otherwise. It allowed us to become the top predator. We use tools and clothing, allowing us to do things other animals can’t and live in inhospitable environments. Compared to other animals, humans employ a rich language. That enables us to express countless meanings and describe situations in precise terms.

We pass on social information, such as who is fit for a particular job. We get information about others in our group without needing personal experience. If someone cheats, you don’t need to learn it the hard way like chimpanzees must, but someone can tell you. That allows us to cooperate more effectively. Most human communication is social information or gossip. We need the group to survive, so we must understand what is happening within our group and the decisions our group needs to make.

Human politics is about cooperating and competing. We must agree on what we should do as a group and on how we divide the spoils of our cooperation. Within the group, we may compete to cooperate. Leadership contests benefit the group when the outcome is better leadership. That isn’t always the case, and infighting can weaken the group. We also cooperate to compete. We organise ourselves in groups to compete with other groups, such as defeating them in warfare.

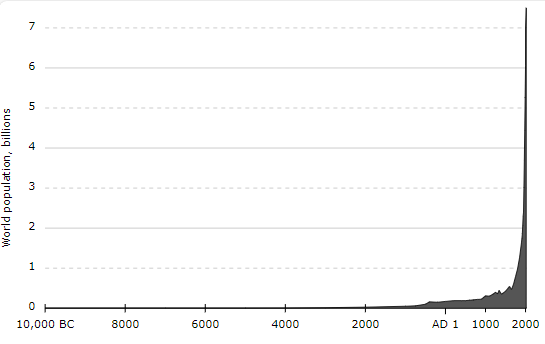

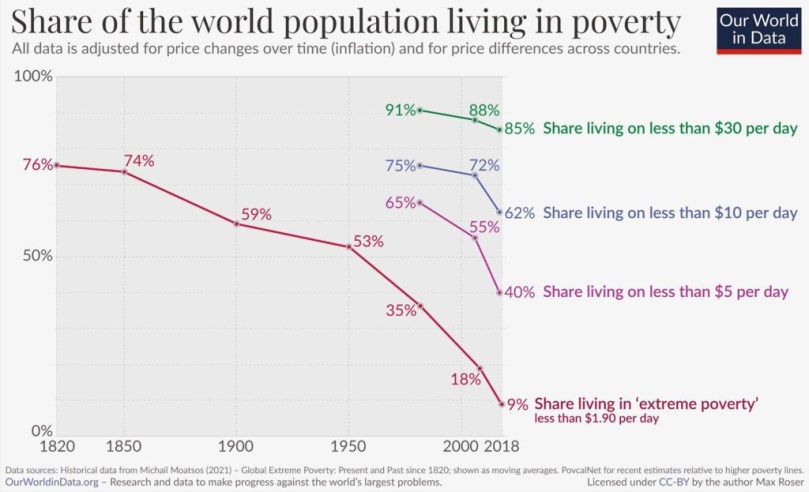

Early humans lived in bands of up to 150 individuals. The number of individuals with whom we can closely collaborate is one of our natural limitations. We overcame the limit of our natural group size by cooperating based on shared imaginings, such as religions, laws, money, and nation-states. That competitive advantage over other species allowed us to take over this planet and become the ‘killer bug’ that has completely upended nature and has terminated more species than any other species.

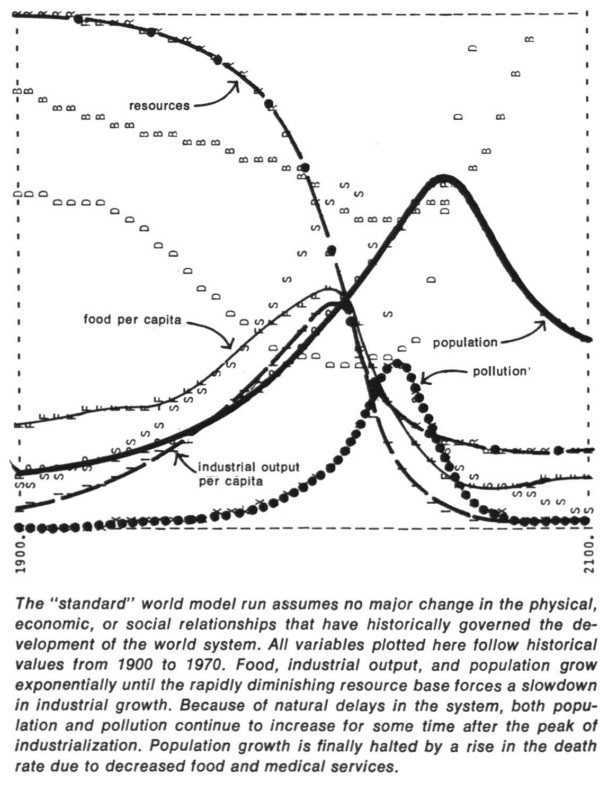

Unlike other animals and plants, which adapt to their environment, we have altered our environment to suit us. We have created societies and civilisations and have become immensely powerful collectives to compete with other collectives. However, our civilisations also shield us from the forces of nature, turning us into weak individuals. We have become integrated into the system, and many of us won’t survive a collapse of civilisation. It is crucial to understand that competition drives this process.

We imagine corporations, laws, money, and nation-states. We believe a law exists, and that is why the law works. It is also why religion works. These shared imaginations allow us to cooperate on any scale for any purpose. We are programmable, with our brains serving as the hardware and our imaginations serving as the software. And we can change the software overnight. During the French Revolution, the French stopped believing in the divine right of kings overnight and began to envision the sovereignty of the people.

Organising to compete

The forces of competition and population density drove humans to organise. There is a competition between groups of humans. Just as there is a competition between species in nature, there is also a competition between human groups. Groups that succeeded in adapting to new circumstances survived those that did not. We are rule-following animals. Once we start to cooperate on a larger scale, we need political institutions that embody the rules of a community or society.

Humans design political institutions while genetic mutations emerge by chance. Still, competition determines which designs survive and become copied. In general, under the pressure of competition, which mainly was warfare, human organisation advanced from bands to tribes to feudalism to states. The experts deem this explanation simplistic and flawed. Still, overall, that trend towards more advanced organisation occurred.

Hunter-gatherers lived in family groups of a few dozen individuals. They had few violent conflicts, probably because they had no property, and population density was low. Hunter-gatherers could move on if a stronger band invaded their territory. Small groups were egalitarian. They often had no permanent leader or hierarchy and decided on their leaders based on group consensus.

The Agricultural Revolution changed that. Farming allows more people to survive. Farmers invest heavily in their cattle and crops, so agricultural societies need property rights and defence forces. Agriculture promoted the transition from bands to tribes. Population density increased, leading to more frequent violent conflicts among people. Tribes are much larger than bands and can muster more men for war, so tribes replaced bands.

Tribes were usually egalitarian, but a separate warrior caste often emerged. The most basic form of political organisation was the lord and his armed vassals, known as feudalism. The lord and his vassals exchange favours. The loyalty of the vassals is crucial, and politics is about these loyalties and betrayals. Tribalism centres around kinship, but also includes feudalist, personal relationships of mutual reciprocity and personal ties.

States yield more power than tribes because they force people to cooperate, while tribes work with voluntary arrangements. As population density increased and people lived closer to each other, the need to regulate conflicts also grew, so some states also provided justice services. Leaders, with their family and friends, led these states. They worked with personal, feudal relationships, thus making deals and returning favours. And so, the transition from tribes to feudalism to states is not a straightforward process.

The first modern, rationally organised states with professional bureaucracies based on merit rather than personal relationships and favours appeared in China. The reason was a centuries-long cut-throat competition of warfare on an unprecedented scale, with states having armies of up to 500,000 men, in the period now known as the Warring States Era. Fielding these armies required professional tax collection, with records of people and their possessions, as well as the provisioning of soldiers in the field.

Once the state of Qin emerged victorious by 200 BC, China became unified, and the competition between the states ended, and China’s modernisation ground to a halt. Even so, China adhered to modern bureaucratic principles and remained the most modern state for 2,000 years, enabling its rulers to govern a vast empire. States remained the most competitive organisational form until Europeans invented capitalism and corporations, which would cause a radical new dynamic of permanent change driven by competition.

Capitalism and corporations

China had a strong centralised state that prevented the merchants from becoming the dominant force in society. In the Middle Ages, Europe had no strong states, so capitalism could gradually emerge in Europe. The rise of merchants and later corporations brought a new economic dynamic and wealth. Corporations are legal entities serving a specific purpose. Invented in Roman times, they included the state, municipalities, political groups, and guilds of artisans or traders.

From the Middle Ages onward, Europeans introduced commercial corporations with shares and stock markets such as the Dutch East Indies Company (VOC). The advent of corporations triggered a new phase in the competitive cycle, further increasing efficiency by specialising in specific tasks. The Europeans combined their entrepreneurship with inquisitiveness, so eventually the profit motive began to drive innovations as well.

The new dynamic intensified competition and innovation, causing permanent economic growth and disruptive change, a process that economists call creative destruction. Capitalism increases available resources via cooperation or the division of labour, but competition is the driving force. As long as that remains so, competition rather than our desires determines what our future will look like.

Currently, China may have the most competitive socio-economic model, potentially outcompeting those of the West. But it will not end well for them either. Artificial intelligence may soon outcompete humans. It may become a ‘killer bug’ that ends humanity. We can’t keep up with artificial intelligence. The future doesn’t need us. We aren’t sufficiently efficient and innovative. Competition is our first and foremost problem. It is our doomsday machine. Competition, insofar as we allow it, should be at the service of cooperation rather than the opposite. If we don’t do that, we are doomed.

Featured image: Tower of Babel by The Tower of Babel (1569). Public Domain.